Welcome to the Criterion Corner, where we break down some of the month’s new releases from the Criterion Collection.

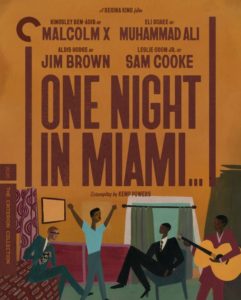

#1106: One Night in Miami… (2020, dir. Regina King)

For one night in 1964, one Miami hotel hosted four of the most influential African-American cultural figures of their time: Black nationalist leader Malcolm X, newly-crowned heavyweight champion of the world Cassius Clay (before he changed his name to Muhammad Ali), NFL superstar-turned-actor Jim Brown, and signing sensation Sam Cooke. The specific contents of that meeting are unknown, but it inspired Kemp Powers to pen One Night in Miami… as a four-man play imagining what these titanic Black cultural figures could have talked about. And in 2020, he adapted the play into a film directed by Oscar-winning actress Regina King, one crackling with the energy of a stage play but brought to life through subtle but emotive cinematic grammar.

Here, the fateful night between Malcolm (Kingsley Ben-Adir), Cassius (Eli Goree), Jim (Aldis Hodge), and Sam (Leslie Odom Jr.) becomes not a simple meeting of minds, but the stage for incisive probing about the state of Black advancement in American culture at that time (and, given its 2020 release, a contemporary America freshly wrestling with issues of racial injustice) and their role in shaping it.

Powers’ script (and King’s direction, deft in its understanding of how to shoot actors and make a drab ’60s hotel room come alive) plays with the dynamics innate to its central figures, all of them at different relationships to both Black and white America. Malcolm is committed to drawing them into militant dismantling of the violent white state, even as his own colleagues in the movement start to push away from him. Sam Cooke, meanwhile, understands the value of building Black wealth and opportunity for himself, even as it means catering to white audiences and ignoring the struggles of social progress. Cassius reels from his newfound fame and the prospect of what that might mean for his own Blackness, while Jim Brown is resigned to play ball and die in movies for white folks who only pretend to care about him. “I hate those motherfuckers more than the rednecks who just put it all out there,” he seethes at Malcolm. “And I’ll be damned if I ever forget what they really think of me.”

It’s dazzling, incisive stuff, elevated by a quartet of performances as grounded in the mannerisms and cadence of their real-life figures as the nuances of their performers. Ben-Adir perfectly crystallizes Malcolm’s frenzied, frustrated sense of urgency against his more complacent counterparts; Odom Jr. is a brilliant, wisecracking foil, all defensiveness wrapped up in that silky voice. Goree nails the singsong bravado of Ali’s speaking voice, which he uses to lay out unexpected insights about his own desire for the power he’s earned, and Hodge’s barely-restrained contempt hiding behind a lothario’s swagger rounds out the ensemble perfectly.

More than a quirky footnote in civil rights history, One Night in Miami… uses this unlikely meeting as a forum to discuss these tensions with incredible alacrity. It’s a rollicking actor’s showcase and searing exploration of race relations in America all in one, and one of the best films of last year.

Good thing, then, that Criterion is continuing its balance of classics with well-curated contemporary films for streaming services that could use some physical media preservation. Like most modern films of its type, the 4K restoration is hardly a revelation; it already looked good on Amazon, where it premiered. But it’s still a crisp, impeccable presentation, lighting the warm browns of the hotel room and the crisp maroons of Cooke’s suit nicely (alongside the great 5.1 surround sound presentation that holds every note of Cooke’s singing voice).

The extras are nothing to shake your head at either, a veritable bevy of interviews and conversations between the cast/crew and other Black critics and filmmakers to reiterate the film’s importance. There’s a great chat between King and Kasi Lemmons (sidenote: when’s Eve’s Bayou coming to Criterion?) about the unique challenges facing Black women directors; another chat with King, Powers, and critic Gil Robertson; an excerpt from a 2021 podcast with King and Barry Jenkins; King with her central ensemble; featurettes on the production and sound design, respectively; and a lovely essay by Gene Seymour that takes time to single out each actor’s incredible contributions to the film.

You can purchase One Night in Miami… from the Criterion Collection website here.

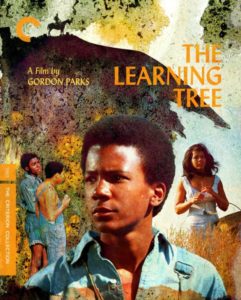

#1107: The Learning Tree (1969, dir. Gordon Parks)

Careers like King’s, however, wouldn’t be possible without Gordon Parks — the famed photojournalist and author who became the first African-American to direct a major studio feature film. Modern audiences likely know him best as the father of the “blaxploitation” genre with 1971’s Shaft, but his film work began in earnest with his debut, a heartfelt coming-of-age story adapted from his bestselling novel The Learning Tree.

Based loosely on his own upbringing in rural Kansas in the 1920s, Park’s first film is a riveting yet nostalgic look back at his childhood, filtered through the stand-in character of Newt Winger (a beautifully vulnerable Kyle Johnson). a quiet, sensitive boy who weathers the racism of his community with a stiff upper lip. Through his eyes, we see the lowered expectations of white superiors, like one teacher who insists that Black kids not bother trying to go to college since it’ll be “an awful waste of money and time,” and the violence that occurs when white men rape Black women with impunity.

Amid these various terrors, Newt projects a patient uncertainty, one driven by a deep knowledge of the anti-Blackness his world exudes but unwilling to stoop to its level. This is exacerbated when he becomes embroiled in a trial over the death of the neighboring farmer Jake Kiner, forced to choose between implicating the Black man who really did it or sentencing an innocent white man to death.

But that sense of calm is contrasted by his friend Marcus (Alex Clarke), who lacks Newt’s aspirations and grows ever more frustrated with the injustices visited upon him by the white neighborhood and police (the latter personified by Dana Elcar’s monstrously mundane Kirky). He lacks Newt’s stable home life, and he seethes with vehement rage at his lot. Even so, Parks’ treatment of both kids is innately empathetic, aided by Burnett Guffey’s sun-dappled cinematography (Guffey came out of retirement after shooting Bonnie and Clyde to shoot Learning Tree, and we should be glad he did).

More than the film itself (which is still eminently watchable and empathetic today), The Learning Tree stands as a landmark moment for Black cinema. As director, producer, writer, and even composer, Parks broke several color lines in the world of American filmmaking on this picture; it opened doors for hosts of Black filmmakers and creators to come after him. What’s more, it was humanistic; contrasted with the blaxploitation bombast of Shaft and others, The Learning Tree was firmly a sensitive coming-of-age story, a stark indictment of white racism that broke stereotypes about Black people, particularly Black boys, as illiterate monsters and servile sages.

Criterion’s treatment of The Learning Tree is commensurate with their typical curatorial instincts, with a host of features meant not just to illuminate the film itself, but Parks as an artist. The 2k restoration is handsome enough, evoking Guffey’s bright, textured cinematography (only getting disappointingly hazy in the credits/effects shots that likely didn’t have the original negative to work from).

From there, there are a host of docs on Parks and the film’s creation, including retrospective looks from Black academics and filmmakers like Nelson George and Ernest Dickerson. Featurettes of Parks on set, including one narrated by Gordon Parks Jr., offer a rare glimpse of a man who understands the pressure his position has placed him in, and his earnest desire to do right for Black filmmakers to come. There are even two 1968 documentaries Parks worked on to lend further context to his prior creative output. Rather than commission an essay, the booklet lets Parks’ lyrical, evocative prose speak for itself — in one 1963 Life photoessay and an excerpt from his 2005 memoir A Hungry Heart.

You can purchase The Learning Tree from the Criterion Collection website here.