(Every month, we at The Spool select a Filmmaker of the Month, honoring the life and works of influential auteurs with a singular voice, for good or ill. Given that July sees the release of Once Upon a Time in… Hollywood, the ninth film from Quentin Tarantino, we’re exploring the filmography of one of 20th-century cinema’s most breathlessly referential directors. Read the rest of our Filmmaker of the Month coverage of Tarantino here.)

I first saw Quentin Tarantino‘s Death Proof in the theater as part of its release as a double feature with the Robert Rodriguez film Planet Terror. I fully expected to adore the latter, with its image of Rose McGowan as a badass stripper who fought zombies with a machine-gun leg. Imagine my surprise then, when it was Death Proof, not Planet Terror, that left me elated.

It’s the kind of feeling that didn’t, and couldn’t last, and not just because some extremely problematic revelations have since been unearthed about both directors. Granted, I still enjoy some of the cinematic flourishes that act as tributes to classic Grindhouse movies, and which others may rightfully find grating. It’s not hard to understand why some would find intentionally damaged-looking film and missing reels irritating, since such staples were due to working without the resources Tarantino has in abundance.

You’ll certainly either love or hate the film’s many fake trailers, some of which, like Machete and Hobo with a Shotgun, were made into real films. However, even I’m thankful that Eli Roth’s Thanksgiving, and especially, Werewolf Women of the SS, weren’t expanded upon. Nicolas Cage being his most deranged self in that little fake beard as Fu Manchu was hilarious, but between cultural appropriation and actual Nazis (cough, excuse me, the alt-right) taking over government, it just wouldn’t be funny after the two minutes it takes for the trailer to roll.

Once you get to the actual movie, there’s still a lot to like. In Death Proof, Tarantino builds his most carefully calibrated plot, with all dialogue painstakingly tailored to each character. The first three women that the murderous Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell), a former movie stuntman, stalks in Austin, Texas have distinct personalities that are deeply shaped by region, whether it’s Texas in the case of Shanna (Jordan Ladd), Brooklyn for Arlene (Vanessa Ferlito), or something more indeterminate in the case of Julia (Sydney Tamiia Poitier).

If you know any of the basic slasher rules, their fate is pretty obvious. One of the first things Shanna, Arlene, and Julia do when they set out together is to ask if anyone has weed. If that wasn’t a red flag, Arlene talks about getting hot and heavy with a guy, even if she stops short of actual sex. They also don’t seem too fond of each other much of the time, with Julia regularly being catty with her girlfriends, and taking far too much pride in her local celebrity status as a DJ who’s featured on several billboards around Austin. Julia even sets Arlene up on the radio to give a guy a lap dance.

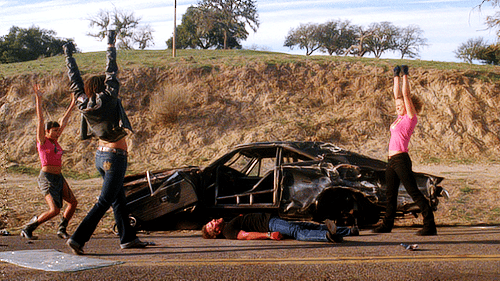

So sex, drugs, and unlikability? It all spells doom for them, and sure enough, they all perish after Mike purposefully crashes into them with his car, killing them all while only suffering minimal injuries, since his car is built for stunts and thus “death proof.”

Fourteen months later in Lebanon, Tennessee, the next women to catch Mike’s attention are much different. Abernathy (Rosario Dawson), Kim (Tracie Thoms), and Zoë (stuntwoman Zoë E. Bell, playing a fictionalized version of herself) not only all work in film, they never smoke weed, and they’re either firmly paired up with steady boyfriends, or they keep it PG with any love interest they do have. Zoë and Kim are also gearheads, and it is their desire to drive a 1970 Dodge Challenger from Vanishing Point that leads to one of the most incredible stunts I’ve ever seen on-screen.

How to describe it? Zoë, Kim, and Abernathy decide to play a game called Ship’s Mast, which involves Zoë sitting on the car’s hood while Kim drives. This is when Mike chooses to follow them and ram their car while Zoë hangs on for dear life. It is isn’t just that Bell is actually on the hood of the car during a high-speed chase with no CGI involved, it’s how the women respond. They’re strong, smart, and capable, but they also react the way anyone would in this situation. They scream and cry, with Zoë outright telling Kim she’s scared.

These three not only survive — they also track Mike down and give as good as they got. They manage to shoot Mike, beat him with a pipe, and after another chase in which they are the pursuers, they ram him right off the road. After, they pull him from his car and take turns beating him, with Abernathy dealing the killing blow.

I left the theater basking in the triumph of a group of women who not only proved capable of saving themselves but avenging others. They were emotionally and physically strong, with each punch they threw depicted as a powerful force that brought Mike down.

But once the adrenaline high wore off, there were still things that made me uncomfortable, even at the time. And in the wake of #MeToo, and the ways in which Tarantino has confessed to enabling Weinstein’s behavior has only made it worse. Death Proof is not only one of Quentin Tarantino’s most carefully constructed films, but it’s also his most fascinating. It shares many of the same characters with Planet Terror and his other films, with plenty of callbacks fans will recognize.

Death Proof is also one of Tarantino’s most fetishistic films, beginning with a shot of a woman’s feet on the dashboard of a car, and plenty of other instances where women are sexualized and fetishized, both by him and Mike. As for the women themselves, their dynamics feel like a guy’s version of Cool Girls, especially for the second group. There’s actually four of them, but Lee (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) is left out of the main action. The reasons why make her symbolic of many of the toxic elements of Death Proof, despite its attempts at empowerment.

Death Proof is not only one of Quentin Tarantino’s most carefully constructed films, but it’s also his most fascinating.

Lee stands out from the start. She’s the only one who’s an actress, talks about having sex, and is dressed in her cheerleader costume. She is also the one left behind while the others take the car for a spin that will lead them right into Mike’s crosshairs. They were allowed to take it for a test drive because Abernathy, as part of her efforts to prove she’s cool enough to hang with Kim and Zoë, decided to tell Jasper (Jonathan Loughran), the car’s owner, that they’re working on a porn movie, then leaves Lee alone with him. Lee is sleeping while this arrangement is made, and she awakes just in time to see her friends drive off. This is the last we see of her, with her final line being, “Gulp.”

It’s hard to imagine women acting like this under any circumstances. Much had been made and written about the Guy/Bro Code, but there’s a Girl Code too. While the former is mostly revolves around avoiding embarrassment, the latter is generally about survival. I cannot imagine any time women would actually leave another woman with a guy who seemed pretty pervy, and it was one of the first things Rose McGowan and Rosario Dawson objected to in a Rolling Stone interview about the film at the time. (The interview itself is something of a time capsule in how much was left unsaid for so long.)

Quentin Tarantino writing and directing a story about a car that harms women is rather… surreal in hindsight, given that this is how his former muse and collaborator Uma Thurman was injured on the set of Kill Bill, the film he made only a few years prior. Death Proof feels like an attempt by the director to absolve himself by having women take their fatal revenge on Mike, thus freeing Tarantino.

Looking back, it feels like an eerily accurate prediction of the future, which saw him, Weinstein, and other powerful men being taken down by the very women they victimized and believed were powerless. And if men like this continue to be held accountable, at least the ending is something I can still appreciate about Death Proof.