Decades on, the legendary animator’s science fantasy is eccentric, messy, and striking.

Although his name and efforts are often diminished or ignored by many histories of 1970s American cinema, Ralph Bakshi was one of the most audacious filmmakers of the era. Not only did his films tackle issues regarding race, sex, and class in graphic and sometimes profane ways, he did so within the framework of feature animation—a format that many, particularly in the U.S., equated almost entirely with family entertainment.

Bakshi’s first film—a feature adaptation of R. Crumb’s Fritz the Cat (1972)—would go on to become a cult sensation, and his follow-up, Heavy Traffic (1973) would also do well. But the racially-charged Coonskin (1974) did better at sparking controversy than selling tickets. And his ambitious live-action/animation hybrid Hey Good Lookin’ would be completed in 1975 but sit on a shelf for years until finally receiving a token release in 1982 in a radically reconceived form which excised almost all of the live footage.

Perhaps sensing that the marketplace was becoming less receptive to the narratives he had specialized in up to that point, Bakshi made a serious pivot with his next project. This was 1977’s Wizards, his first foray into the world of fantasy—a genre that he had been interested in since childhood, and one which would be a significant chunk of his subsequent screen output.

In many ways, Wizards is the quintessential Bakshi film: a sometimes fascinating, sometimes cringe-worthy, and undeniably ambitious work made without the time and resources to fully realize those ambitions but always interesting.

Several million years in the future, Wizards takes place on a post-apocalyptic Earth where most of the survivors have been transformed into radioactive mutants. The few unscathed members of humanity have been replaced with fairies, elves, and dwarves in the land of Montagar. Montagar is ruled by the benevolent fairy queen Delia, who gives birth to twin wizard sons: the kind and benevolent Avatar and the evil mutated Blackwolf. After Delia’s death, Blackwolf attempts to seize control but is defeated in battle and banished from the land by Avatar. Exiled, Blackwolf vows revenge.

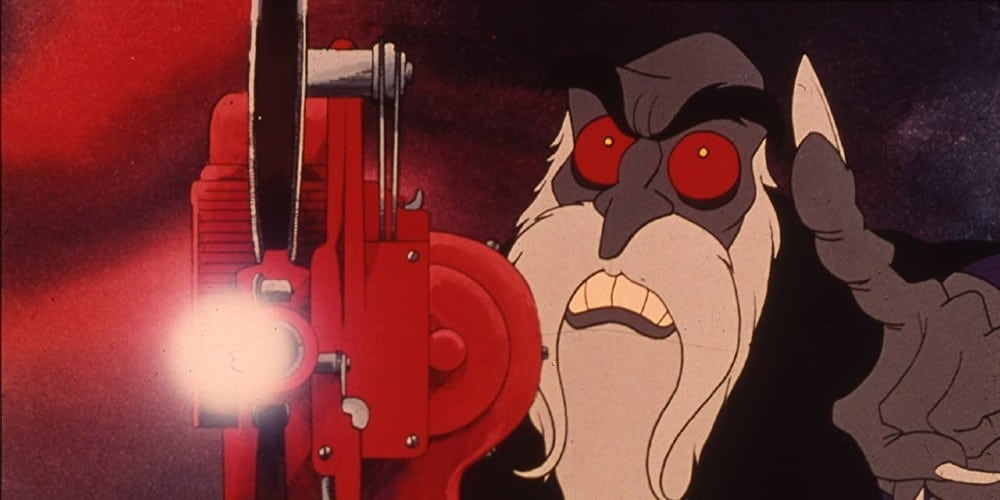

3,000 years later, Blackwolf, now leader of the bleak and mutated land Scortch, tries to act on his long-planned vengeance. His first two attempts fail due to a lack of zeal among his troops. But after discovering an ancient film projector and reels of WWII-era Nazi propaganda, the evil wizard bends the hatreds of the old world to his ends, magically enhancing it to inspire his soldiers and strike fear in the hearts of the Montagarians. When Avatar, who is now training Elinore— the daughter of Montagar’s president—to become a fairy, learns of the magical machine and its powers, he, Elinore, a reprogrammed war robot named Peace, and the elf Weehawk set off on a perilous journey to confront Blackwolf, destroy the projector and prevent the world from suffering another Holocaust.

Narratively, Wizards is simultaneously borderline incomprehensible and oftentimes too on the nose for its good. The opening scenes, which recounts millions of years of history to set up the picture’s key story points, are rushed through at a bewildering pace. It then shifts to an allegory about the potential dangers of technology and propaganda when they fall into the wrong hands, as well as the renewed rise of fascism. Needless to say, it’s a lot for a film that clocks in at 80 minutes to cover, particularly one that’s also juggling an entire science-fantasy bestiary, and these myriad elements never quite pull together. That said, the mere fact that Bakshi was willing to tackle such heavy issues in a post-apocalyptic fantasy is ample proof of his ambitions as an animator, filmmaker, and storyteller.

Wizards’ style is distinct, even odd. Most of the picture bears Bakshi’s established visual style—a form born at least in part by the absence of pencil tests and storyboards due to time and economic pressures. But it also draws on the work of renowned illustrator Vaughn Bode, especially when it comes to the look of Avatar, who bears a resemblance to Bode’s underground comics character Cheech Wizard. To crank Avatar’s oddness up further, Bakshi evidently directed actor Bob Holt to deliver all of his lines with a voice that suggests the familiar cadences of Peter Falk.

When Bakshi ran short on money and was unable to convince 20th Century Fox to increase Wizards’ budget, he turned to rotoscoping—a process in which animators paint over live-action film footage to create the illusion of realistic motion in a relatively quick and easy manner—for Wizards’ big battle scenes. For their choreography, he utilized stock footage and moments cribbed from films including El Cid, Alexander Nevsky, and Patton. To depict the propaganda Blackwolf deploys to hypnotize and terrify the masses, Bakshi used actual Nazi propaganda footage from WWII. The sight of Adolph Hitler an animated science fantasy is jarring, especially considering that one of Bakshi’s goals with the picture was to capture a family audience—one which was, in the late 70s, woefully underserved by usual market leader Disney.

In other words, Wizards is decidedly uneven. To speak personally, I vastly prefer it to Fritz the Cat (a film whose appeal continues to elude me to this day), but it lacks the drive, cohesion, and humor that made Heavy Traffic and Coonskin stand out. Its visual style is undeniably interesting, but I wish that Bakshi had been given the money to fully execute his vision of the battle scenes instead of necessity dictating that he turn to the visions of others. Wizards is perhaps best taken as a testbed for the techniques Bakshi would employ in his later fantasy epics, 1978’s The Lord of the Rings (adapting roughly half of Tolkien’s story and not successful enough to get the second half made) and 1983’s Fire and Ice (a wild collaboration with famed artist Frank Frazetta)—both of which would find him shooting his own footage with actors and then rotoscoping the material.

In the wake of Wizards, Bakshi continued to challenge the norms of animated filmmaking through subsequent projects including the fantasy epics mentioned above, 1981’s American Pop (a chronicle of the history of American popular music that remains Bakshi’s most fully-realized vision to date), the 1982 version of Hey Good Lookin’, 1992’s infamous Cool World, (a live-action/animation hybrid pitched as an R-rated Roger Rabbit that was substantially revised during its production and was massively bombed upon its release) and a 1994 live-action reimagining of the B-movie favorite Cool and the Crazy made as part of Showtime’s Rebel Highway series. He worked on a fair bit of television as well—most infamously a well-received 1987 revival of Mighty Mouse. Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures boosted the careers of several emerging animators, including Batman: The Animated Series‘ Bruce Timm, but was canceled after the arch-conservative American Family Association claimed that one episode featured Mighty Mouse snorting cocaine. (It was flower petals, FYI). After 2015’s short Last Days of Coney Island (which he subsequently released for free on YouTube), Bakshi retired from the industry.

Wizards is messy. It would not be the first film that I’d use as proof of Bakshi’s gifts. (That would be either the lovely American Pop or his surprisingly effective and visually impressive take on Lord of the Rings.) And yet, even accounting for its messiness, Wizards possesses a genuine, idiosyncratic personality. It’s a breath of fresh air in a time when too many fantasy films are too fearful of damaging their IP value to dare the personal or the strange.