A half-century on, we look at the fast and furious American arthouse car flick that became, against all odds, a landmark of independent cinema.

By the time Danny Peary’s seminal text Cult Movies was published in 1981, I was already a dedicated movie buff and familiar with a number of the titles it covered. However, there were plenty I hadn’t encountered. So, I made it a point to seek out and watch all of the ones that I hadn’t seen yet.

As this was at a time when neither cable nor VCR’s widespread, the hunt was occasionally frustrating. Eventually, I was able to check them off one by one, even such adults-only fare as Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, Behind the Green Door, Pink Flamingos, and Emmanuelle.

However, there was one title that remained frustratingly out of reach for the longest time: Two-Lane Blacktop. A low-budget existential road movie that debuted with an extraordinary amount of hype, it flopped so badly that it practically vanished from existence. Those who did embrace it during its brief period of commercial existence kept the flame alive, but it was virtually impossible to see outside of the very occasional revival screening.

In 1994, Seattle’s beloved Scarecrow Video put together a petition to convince Universal Studios to finally put it out on home video. While the campaign received coverage in magazines ranging from People to Film Comment, Universal demurred, ostensibly because the cost of resolving music rights issues would be too high. Quite possibly, it was also because they didn’t want to once again be reminded of its initial failure.

On the bright side, the renewed interest in the film around this time caused it to briefly reappear on the revival circuit. On an early November night in 1996, I went to Chicago’s beloved Facets Multimedia and was able to see it at long last. Of course, having waited to see it for so long that there was always the danger that I had built it up in my mind so much that there is no way that it could have possibly lived up to expectations.

And yet, it would prove to do just that. It took what sounds on the surface like a cheesy bit of exploitation and transformed it into something wholly unique, a piece of utterly original art-house Americana utterly unlike anything before or after.

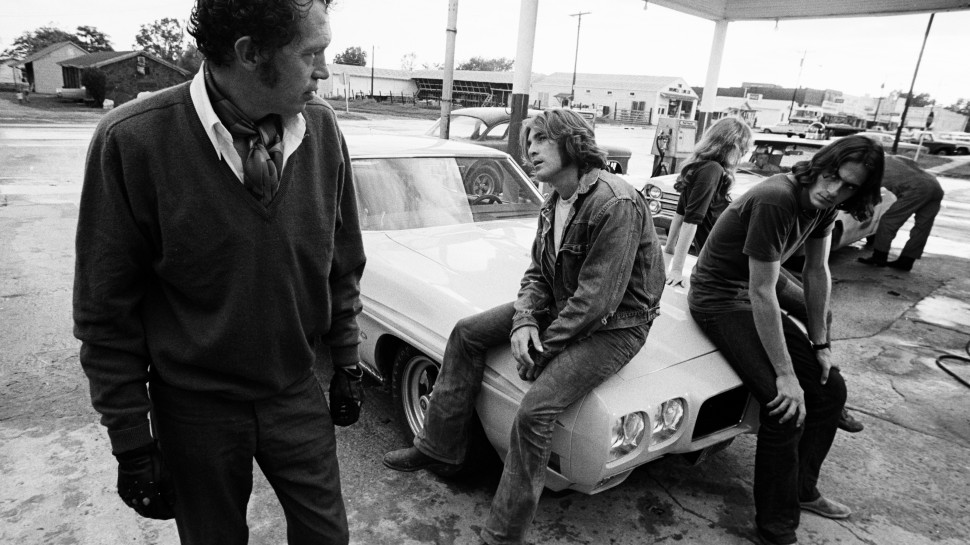

As the film opens, a pair of street racers known only as the Driver (James Taylor) and the Mechanic (Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson) bomb around in their souped-up 1955 Chevrolet 150 sedan, making money by challenging locals to drag races. The two seem content—or they would if they demonstrated anything resembling emotions—but their lives, as highly calibrated and precision-tuned as their auto, are soon thrown into upheaval with the introduction of two other people.

A piece of utterly original art-house Americana utterly unlike anything before or after.

The first is the Girl (Laurie Bird), a hitchhiker who just gets into their car in Flagstaff, Arizona without saying anything. The Driver is clearly enamored with her, but it’s the Mechanic she sleeps with while the Driver goes out drinking by himself.

The other is GTO (Warren Oates), an older man the three encounter in New Mexico who’s driving around in the classic muscle car he nicknamed after and picking up hitchhikers (including one played by the great Harry Dean Stanton). Although not a racer, per se, he proposes to the Driver that they have a cross-country race to Washington D.C. The victor will claim the pink slip to the loser’s car. The race begins, but neither competitor seems hell-bent on winning. At one point, the Driver even takes over behind the wheel for GTO when he becomes too fatigued to continue.

At the same time, the relationships between the four characters begin to shift and twist around. While the Driver and the Mechanic find their friendship threatened by their respective feelings for the Girl, she jumps into GTO’s car until he proposes that they head off to Chicago. Where the story goes from this point I shall leave for you to discover. However, those hoping everything will meet with a thrilling climax may be disappointed. (Also, yes, the final shot is supposed to be like that.)

Two-Lane Blacktop was the brainchild of two of the most fascinating, most overlooked talents of ‘70s-era American cinema. The first was Monte Hellman, a director who had spent the previous decade making low-budget films for Roger Corman, who at the time was directing new scenes for older Corman films to make them long enough to fill television slots.

Producer Michael Laughlin offered Two-Lane Blacktop to Hellman to do, and he agreed — on the condition that he could bring in another writer to rework Will Corry’s original screenplay.

His choice for a writer was Rudy Wurlitzer, whose first screenplay, the post-apocalyptic mind-bender Glen and Randa, had been produced in 1969. Wurlitzer threw out everything from the original script except the basic characters of the Driver, the Mechanic, the Girl, and the notion of a cross-country race. He then wrote an entirely new script in four weeks. When the original financing fell through, the project was shopped around and Hellman landed a deal at Universal Studios that gave him $850,000, complete control over the casting, and final cut.

If that sounds like an unusually sweet deal for such an admittedly esoteric film with no real movie stars in the cast, it is. This was the period immediately following the massive success of Easy Rider. None of the studios understood that film, but it inspired them to give money and freedom to young filmmakers in the hopes of making lightning strike twice.

Nevertheless, a strange level of hype began to surround the film that culminated with a cover story in the April 1971 issue of Esquire magazine that hyped it as “the movie of the year.” It even reprinted the entire screenplay. Unfortunately, as would prove to be the case with so many films made to emulate the success of Easy Rider, Universal hated the film. They ended up dumping it in theaters around early July, which was nowhere near the prime release period it’d eventually become, with minimal advertising. As a result, it was pulled after a couple of weeks.

In theory, there’s very little to the film on the surface that would appeal to me at all. The allure of the road does nothing for me, and my feelings towards James Taylor pretty much echo those evoked by Lester Bangs in his infamous essay “James Taylor Marked for Death.” And yet, when I saw it for the first time that November night in the crowded Facets screening room, I was absolutely mesmerized by it and I continue to be held by its spell today.

It’s sort of a dangerous film to recommend because it so completely subverts audiences’ expectations. Those who don’t quite make it onto its admittedly unique wavelength may find it to be a pretentious bore. However, I was fascinated by the way it started out as a fairly standard narrative involving eminently exploitable elements such as cars, women, and rock music but soon transmogrified into something abstract and unknowable.

I was surprisingly taken with the work done by Taylor, Wilson, and Bird. They may not be great actors in the classical sense, but each one has a unique presence that adds immeasurably to the proceedings. Oates, not surprisingly, is awesome as always, but it’s fascinating to watch him playing against the others without dominating them.

I enjoyed the occasional moments of sly humor here and there as well as the moments of quiet tension that develop; you can’t be sure where a scene is going. And yes, I even enjoyed the trippy finale, one that may lose a little bit of its impact when seen on the neutered soundtrack video release instead of in the theatre but nevertheless concludes on just the right note of ambiguity.

After the music issues were settled, the film finally arrived on home video in 1999 and would become a part of the Criterion Collection a few years later.)

In the wake of the failure of Two-Lane Blacktop, both Taylor and Wilson returned to their day jobs and stayed away from future acting endeavors. Taylor became an enormously popular singer-songwriter and Wilson returned to the Beach Boys until he drowned in 1983.

Bird appeared in only two more films, Cockfighter and Annie Hall, before taking her own life in 1979 at the age of 25. Wurlitzer would go on to write the screenplays for such future cult favorites as Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and Walker, and wrote and directed the very strange Candy Mountain.

As for Hellman, who passed away this past April at the age of 88, his career path would veer as wildly astray as the auto race in his film. Besides the aforementioned Cockfighter, he did uncredited work on the programmers Shatter and Avalanche Express before making the offbeat Western China 9, Liberty 37; the crazy psychosexual period thriller Iguana; and the underrated Silent Night, Deadly Night 3, Better Watch Out!.

After an interval of nearly two decades, he finally returned to the director’s chair by helming “Stanley’s Girlfriend,” a Kubrick-inspired tale that was the best segment of the multi-director horror anthology Trapped Ashes, then following that with his final project, Road to Nowhere.

It’s weirdly fitting that at the same moment that Two-Lane Blacktop is celebrating its 50th anniversary, the number one film in the country is another Universal property that began life as a simple story involving street racers, before shifting into something altogether different.

While F9 is clearly the more successful film from a financial perspective, it’s one that offers up little more than 150 minutes of empty cinematic calories. That can be fine—not so much in that particular case, though—but if you prefer your car-based entertainment to contain more existential dread and fewer automobiles being launched into outer space, Two-Lane Blacktop should prove to be your kind of ride.