Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableDavid Lynch’s 1990 thriller remains a scintillating, if inessential, piece of the filmmaker’s gonzo catalog.

Like many others, I consider David Lynch to be one of the most unique and distinctive voices to emerge in the entire history of cinema. He has only made 10 feature films to date (the groundbreaking Twin Peaks saga is a television series, so let us nip that discussion in the bud). But of those, I would not hesitate to call three of them—Eraserhead (1977), Blue Velvet (1986) and Mulholland Drive (2001)—stone-cold masterpieces. Most of the rest of his output—including The Elephant Man (1980), Fire Walk With Me (1992), Lost Highway (1997), The Straight Story (1999) and Inland Empire (2006)—is not that far behind.

Hell, even his usually maligned and generally misbegotten adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1984) has proven itself to be a stunning visual marvel that is a lot better than its reputation might suggest.

However, if I were inexplicably forced to kick one of Lynch’s films to the curb, I would not hesitate for a second to select Wild at Heart. His wild and woolly road movie made its tumultuous debut at the 1990 Cannes Film Festival, where it won the Palme d’Or. This capped off a period in which he had unexpectedly gone from being the avant-garde weirdo behind Eraserhead to the most talked-about artistic voice in America not named Madonna in the wake of Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks.

To be fair, Wild at Heart is not “bad,” per se—no Lynch film could ever really be—as much as it is non-essential. It’s the one time in his career where it feels as if he’s consciously trying to meet expectations of what a “David Lynch movie” should entail, instead of following his personal vision. That said, even though I wouldn’t go out of my way to rescue it from a flaming warehouse—an apt metaphor considering its fire-heavy visual motifs—it still contains enough strong and interesting stuff to make it worth watching.

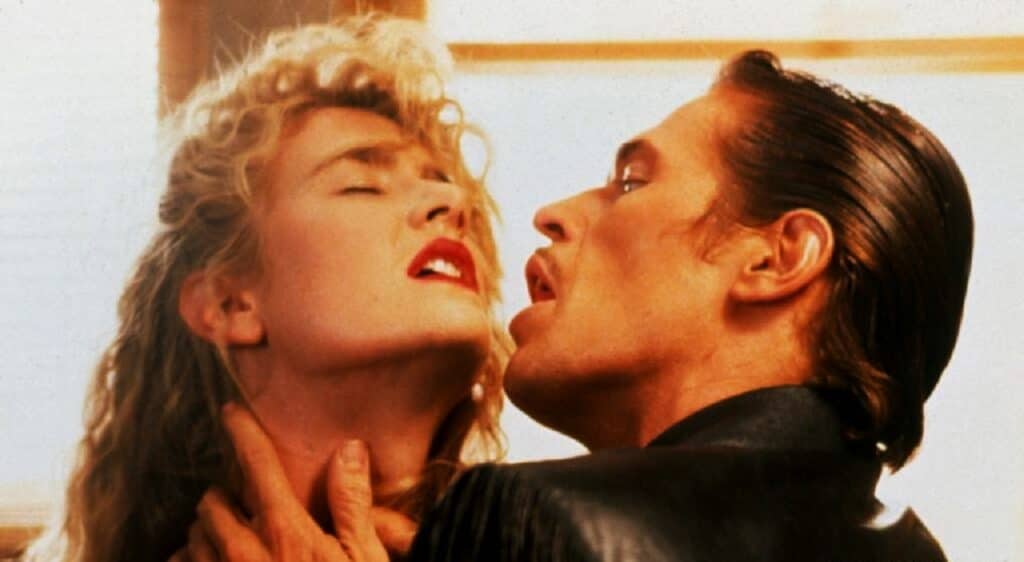

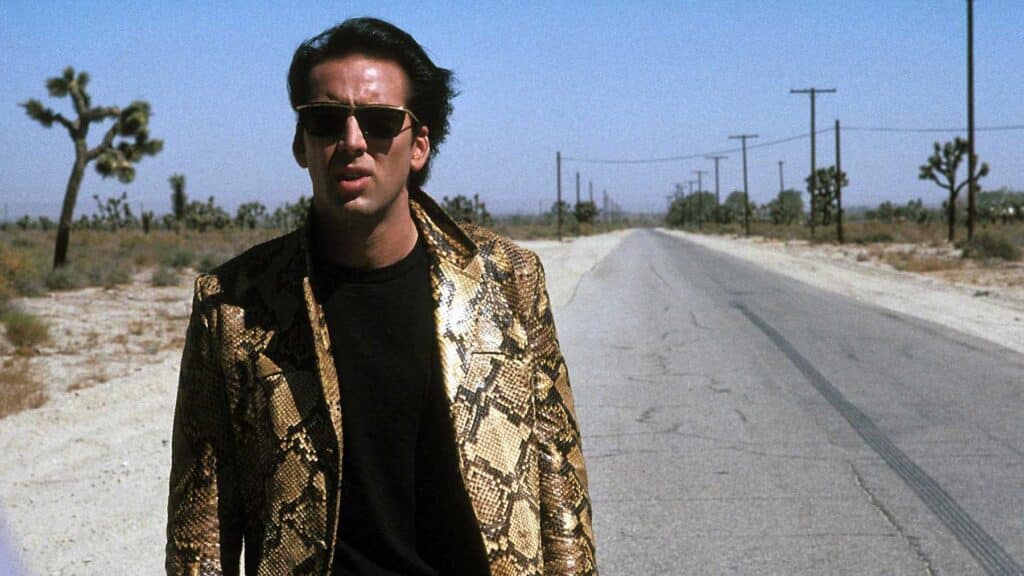

Adapted from the novel by Barry Gifford, Wild at Heart tells the story of a pair of star-crossed lovers, the Elvis-obsessed bad boy Sailor Ripley (Nicolas Cage) and the hot-to-trot Lula (Laura Dern), much to the consternation of her mother, Marietta (Diane Ladd). Marietta even goes so far as to hire a goon to kill Sailor during a party. Sailor brutally beats his assailant to death and winds up doing 22 months for manslaughter. Upon his release, Lula is waiting for him and the two decide to hit the road for a journey fueled mostly by hot sex and loud music, with Marietta sending not one, but two lovers/investigators (first Harry Dean Stanton, then J.E. Freeman) after them.

If projects like Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks observed the weirdness and depravity lurking just below the surface of Americana at its most seemingly bucolic, this film blasts away that veneer and allows the weirdness and depravity to rise to the surface. (“The whole world is wild at heart and weird on top.”) If Frank Tashlin and Russ Meyer were to have combined their respective skillsets to make an Elvis Presley vehicle in which he fully indulged in all the dark desires he once represented instead of playing yet another racing enthusiast singing about clambakes, it might well have resembled this film.

It’s the one time in his career where it feels as if he’s consciously trying to meet expectations of what a “David Lynch movie” should entail, instead of following his personal vision.

The problem with Wild at Heart is that, while flashy and entertaining on a surface level, it quickly becomes apparent that Lynch has no interest in going any deeper than that. Lynch presents all the key characters in frankly iconic terms, identified more by their accoutrements than anything else. Sailor’s snakeskin jacket is fetishized to such a degree that it practically deserves to be officially named part of the supporting cast.

In reworking Gifford’s novel, Lynch throws a lot of bizarre and occasionally disturbing imagery into the mix (a guy in a bar starts quacking for no reason, all of the Wizard of Oz homages). But it feels force, as if made by a filmmaker desperately trying to imitate Lynch. For the first (and only) time in his entire career, you get the sense that Lynch is being ironic with everything from his basic lovers-on-the-run narrative to the tremendous amount of graphic violence on display. After a while, this attitude gets a little tiresome.

That said, Wild at Heart proves that even Lynch’s weakest stuff is still more compelling than the best efforts of many of his contemporaries. As Sailor, Cage’s take on the Elvis mythos walks a very thin tightrope between parody and homage that never quite tips over towards one or the other. Dern, playing the exact opposite of the good girl role she essayed for Lynch in Blue Velvet, is even better, delivering a performance that is bold, fearless and as good as anything she’s ever done.

The gallery of supporting characters is mostly entertaining as well, especially Willem Dafoe in what remains one of the creepiest performances of his career as an orthodontically challenged gangster named Bobby Peru. (His scene with Dern is a tour de force for both actors you can’t take your eyes off, even when you desperately want to.)

Visually, the film is striking as well; you can practically feel the heat and taste the sweat from Frederick Elmes’s cinematography in every scene. Sailor and Lula’s encounter with Sharilynn Fenn’s car crash victim is one of Lynch’s very best scenes, the one point where Lynch finally kicks the ironic distance aside.

Although Wild at Heart did triumph at Cannes in 1990, by the time it was released three months later the cultural tides had already shifted and the inevitable backlash against Lynch had already begun. Although modestly successful at the box office, it was blasted by many critics who found it to be a lazy and ultimately work that bordered on self-parody.

Between that, the gradually decreasing audience for Twin Peaks during its uneven second season and the total rejection by critics and audiences alike for the movie prequel Fire Walk with Me, and Lynch was officially on the outs. In later years, he would regain his standing with things like Mulholland Drive and the third season of Twin Peaks, and even inspire people to go back and look again at those previously rejected titles.

While many now regard Fire Walk with Me as a masterwork, Wild at Heart hasn’t had quite the same reappraisal. I have the feeling that may never happen. Then and now, it’s nothing more than an okay but ultimately empty work from a master filmmaker rehashing past glories. Compare it to Lynch at his best, and it fizzles away like a drop of sweat on hot Georgia asphalt.