Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableClive Barker’s directorial debut launched a franchise and cemented a place in a comfort movie pantheon.

There’s just too much content these days. Every week a new movie is the talk of the socials, a new show is Tiktok’s sampled darling, and there’s more to consume consume consume. It’s no wonder, then, that the concept of the “comfort movie” has become such a part of the cultural conversation, that people make lists and prompts and videos pushing the simple delights that come with watching something that you’ve seen before. A comfort movie would seem, by its name alone, to encompass a very specific genre, maybe a rom-com or a feel-good family comedy; something that is innocuous and fluffy, but a comfort movie is so much more than that. It’s a film where you know all the beats, where the story never gets old and the performances are never stale, where you can mouth the dialogue along with the characters but also get up and do something else while you’re watching; a comfort movie is there for you to come back to. It’s there for you, every time.

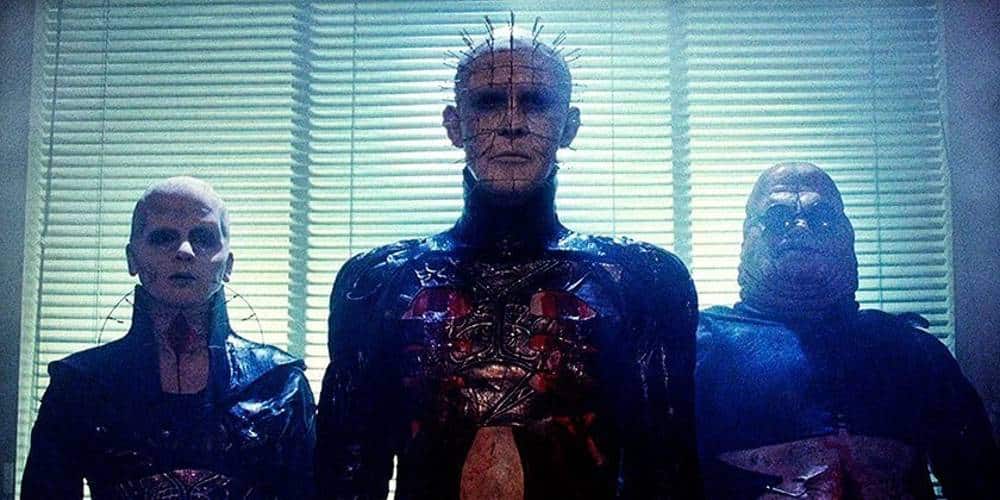

In my case, the ultimate comfort movie is 1987’s Hellraiser, written and directed by Clive Barker and based upon his novella The Hellbound Heart. The plot is, as such plots go, relatively simple: Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman), a hedonist and a nasty piece of work, purchases a mysterious “Puzzle Box” that promises to summon the demon Cenobites, who offer pain and pleasure beyond mortal understanding. Frank is ostensibly killed by the Cenobites and his house is later occupied by his brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) and Larry’s wife Julia (Clare Higgins), a deeply unhappy woman who has never gotten over the brief affair she had with Frank years before. While they’re moving in, Larry cuts his hand, and the blood resurrects Frank, who makes contact with Julia and promises (there are so many promises) to run away with her if she’ll provide more victims for him to feed upon. Larry’s daughter Kirsty (Ashley Laurence) stumbles upon Julia, Frank, and the Puzzle Box and entangles herself with the Cenobites (particularly Doug Bradley as lead Cenobite Pinhead) until she can Final Girl her way out of the situation.

That sounds comforting, doesn’t it? Okay, maybe not on paper, but the goal of a comfort movie isn’t necessarily to be uplifting in its subject matter, it’s in the way it makes one feel. Hellraiser belongs to a personal subset of movies I know by heart, both plot-wise and creation-wise. Made for an astonishing $900,000, Hellraiser is a wonder of practical effects and Christopher Young’s atmospheric music; a weird little oddity that has, to date, inspired nine sequels (one in space!) and an upcoming remake. The film dubs characters that were initially English with generic American accents after New World Pictures decided the story would be better set in the United States, placing the story in a limbo of a London where everyone is American; a city where none of the phones ever quite work right and the hospitals are the real nightmares. Larry and Julia’s house is never quite finished, with damp spots along the upper walls and whole rooms stuffed full of random items (and eventually corpses). Hellraiser works on many levels, but never so much as the utter strangeness of the supposed real world.

It’s these idiosyncrasies that make Hellraiser so damn comforting to me. It’s a plot I know like the back of my hand, but there’s always something new to be experiencing–an extra with a wildly overdubbed voice, a piece of decoration in the Cotton house, or Kirsty’s brave little rented room; even the goofs are sources of joy: when Kirsty is running down a hell hallway from the monstrous Engineer, you can see the little cart it’s being pushed on. It’s an endearing accident that goes far to show the can-do nature of the film’s creation. Besides, The Engineer is a hideous demon from a hell dimension, who’s to say it isn’t just being pushed by more demons? Sure, that’s a theory.

Hellraiser was the directorial debut of Barker, who was moved to direct after disappointing adaptations of his writings had hit theaters as 1985’s Underworld and 1986’s Rawhead Rex. Barker largely learned what directing was on the job, freely admitting his filmmaking knowledge gaps, and it’s this rawness that lends such a sense of otherness to the film itself. Loth am I to declare anything “gritty”, but Hellraiser lifts that descriptor above its general usage. Hellraiser isn’t a polished piece of filmmaking but it is a dark and dingy little picture about people with dark and dingy little lives.

2022 marks the 35th anniversary of this unique piece of work and may it reign for 35 more. I’m sure some would have “theories” as to why this “gooey and unpleasant” (quoth my husband) horror flick about sadomasochistic creatures from another dimension is the movie I go to when I’m sick or tired or need to turn off my brain. Is it watching Kirsty prevail even as her world crumbles around her? Is it delighting in Julia, one of horror’s great female villains? Is it waving one’s hands around helplessly when asked why the movie ends with the sudden appearance of a skeletal dragon? It’s all these things and more, man. It’s Hellraiser.