Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableHBO presents a detailed, unexpectedly moving documentary on the life & times of George Carlin, comedian, wordsmith, & cynical optimist

This review is also a story about my father. Please indulge me for a moment.

My father, Eugene Todd (born 1946, died 2009), wasn’t an easy person to love. He wasn’t even an easy person to like much of the time. Perpetually angry, he used the slights and heartbreak he experienced in his life as ammunition to lob back at other people, framed as cruel, cutting remarks and low-hitting “jokes.” Rather than mellowing out in old age, he got worse, more set in his ways and less willing to see what the effect of his sharp, sarcastic tongue had on other people, including me, his only child.

Other than both of us immediately resorting to sarcasm and cruelty to try to “win” an argument (a habit I’ve worked hard to restrain as I’ve grown older), we didn’t have much in common. We did bond over a few things, though – Taxi Driver, SCTV, and Stephen King books, to name a few. There was also the comedy of George Carlin, which my father loved, and quoted often. Now, Dad and George, they had a lot in common: both of them grew up in a working class family, & had complicated relationships with their mothers. Both of them were fiercely smart, but also high school dropouts. Both of them joined the military, and then left under less than honorable circumstances. Both of them got tangled up in drugs. Both of them grew up with a healthy distrust of authority, though George was able to direct it into his comedy, while for Dad it mostly resulted in losing a lot of low-paying jobs throughout his life. Going bald and with a graying beard by the time he hit his mid-forties, Dad even looked like George, and sounded like him too, sprinkling his sentences with profanities like the Salt Bae of “fuck” and “shit.”

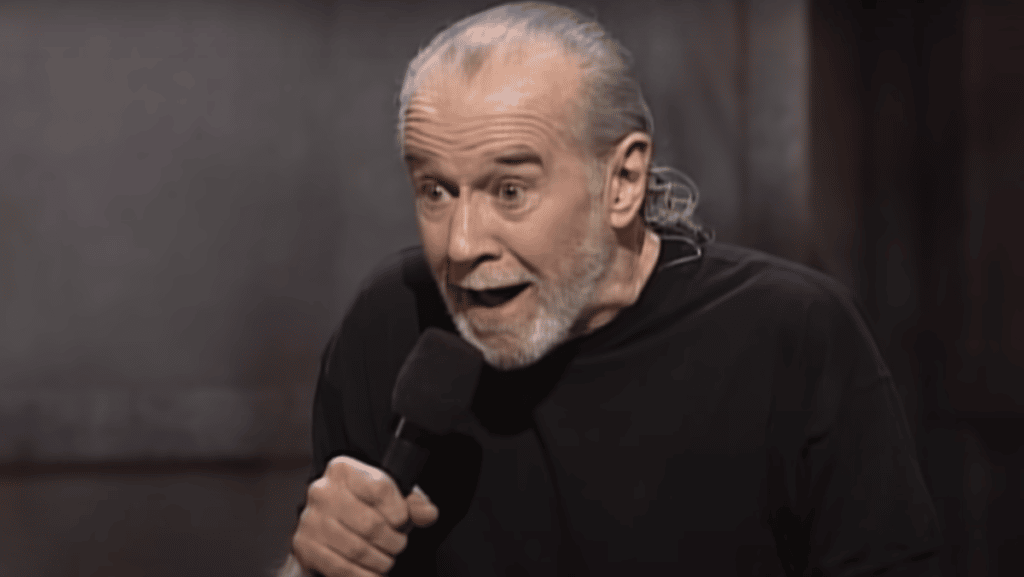

I did not expect to come out of watching George Carlin’s American Dream feeling like I understood my father a little better, but that’s one of the miracles of this beautiful, unexpectedly moving documentary. Produced by Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio, it’s a look not just at Carlin’s rise to fame, and his spookily prescient jokes-that-weren’t-entirely-jokes, but his bittersweet personal life as a devoted but often troubled husband and father. Bolstered by an astonishing amount of archival material, including childhood drawings, calendars, journals, personal recordings, unexpectedly (and extremely sweet) mushy love letters to his wives, and workshopped jokes, it paints a vivid, deeply insightful picture of someone who was less a nihilist than perpetually disappointed and heartbroken over the state of the world, and the country he loved.

Split into two nearly two hour episodes (though it never feels overindulgent), the first half covers Carlin’s rough New York City childhood up to the end of the 70s, when he faced being a has-been at the ripe old age of 43. Though it would seem like barely a blip on his decades long career, a fair amount of time is spent on his attempt at being a clean-shaven, suit wearing “family friendly” comic, inspired by his idol, Danny Kaye. Then he discovered drugs, and remade himself into a member of the long-hair counterculture, during which he created the “Seven Dirty Words” bit, a routine so deeply ingrained into American pop culture that it was even referenced in an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants.

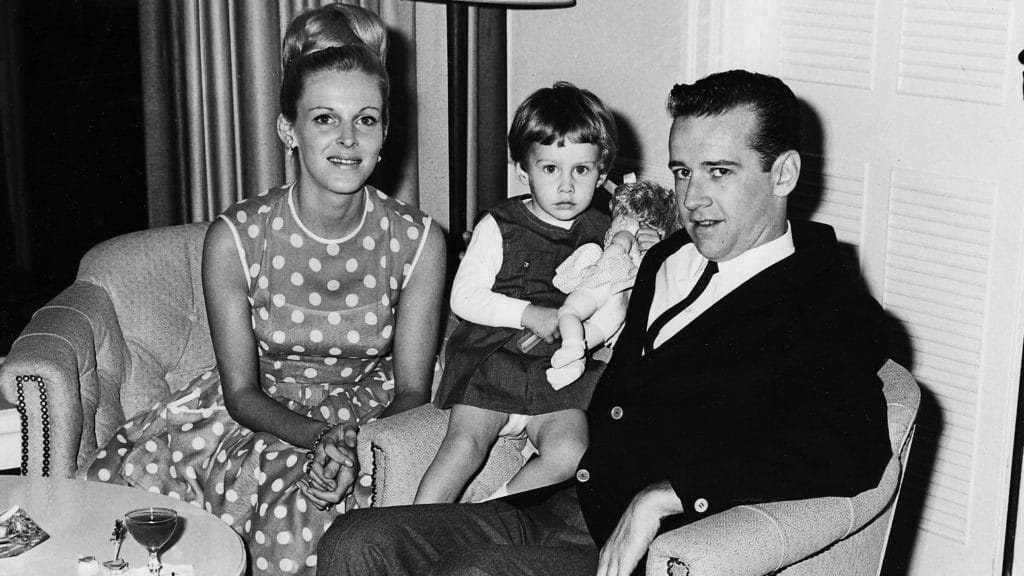

Despite his appearance and persona, Carlin was in a surprisingly traditional, loving but often tumultuous marriage with Brenda Hosbrook, the mother of his only child. It’s here that perhaps the documentary is its most compelling. The two obviously adored each other, but Carlin’s old-fashioned streak often clashed with Brenda’s desire to be involved in his career, and the conflict, exacerbated by Brenda’s alcoholism and Carlin’s cocaine addiction, nearly led to disaster. Carlin’s daughter, Kelly, doesn’t shy away from depicting them as equally difficult, and often too caught up in their own pain to see how their actions were affecting both each other, and their child. Their mutual decision to get clean and save their marriage (both successful endeavors) is a lovely moment of triumph in a film genre that too often focuses on misery and downfall.

The second half focuses on the early 80s through the end of Carlin’s life, as he remakes himself again, focusing less on absurdist humor and more on current events, and tempering his jokes with brutal, often sobering honesty. Though Carlin would find his most enduring success through a series of HBO specials, his comeback was not without a lot of heartache, including tax woes, mounting health issues (a running bit for a while was his “competition” with Richard Pryor over which one of them had the most heart attacks), and eventually, worst of all, the death of his beloved Brenda from liver cancer. Though Carlin would find love again with comedy writer Sally Wade, who was with him up until the end, Brenda’s death seemed to mark another turning point in his comedy, a darker, more bitter turn in which he openly discussed his atheism (despite being a traditional Catholic boy at heart) and his refusal to believe in the concept of a God who supposedly loves his flock, but also causes them so much pain.

Though many (including myself, initially) perceived Carlin at the end of his life to be more angry than funny, as his brother (a delightfully profane nonagenarian wearing an earring and a 4/20 t-shirt) explains, it was more that he was despondent over the false bill of goods so many individuals had been sold about the government, the rich and the poor, religion, and the titular “American dream.” Carlin himself says as much, in one of the most incisive moments in the documentary: “What looks like anger is a real contempt for the choices my fellow humans have made. I just feel betrayed by the bullshit in America that’s all around us.”

People often remark that they wish George Carlin was still around so that they could hear what he had to say about the world today. I’m actually glad that he isn’t, just as I’m glad that my dad isn’t. I suspect that neither of them would find much to make jokes about at this point, mostly because so little has changed since Carlin’s blistering “if you’re pre-born you’re fine, if you’re pre-school you’re fucked” screed against Conservative pro-life hypocrisy, all the way back in 1996. Instead of old fashioned, out of touch rich Uncle Pennybags Republicans, now we have actual comic book villains like Matt Gaetz and Marjorie Taylor-Greene, and I think even a literal comedy genius would have trouble finding the humor in that.

However, I would like to know what Carlin would have thought of the ongoing battle between conservatives and liberals to claim him as one of their own, often cherry picking his routines and quoting them out of context (if not making them up entirely, such as a meme that once quoted him as saying we need to “pray more”) to suit their narrative. If conservatives think that Carlin would have aligned himself with Trump, I suggest they listen to his bit on how affordable housing should be built on golf courses. On the other hand, his devotion to free speech and dislike of euphemisms wouldn’t have exactly endeared him to liberals either, and it’s likely he would have had less than enlightened things to say about cancel culture. That was George Carlin’s whole deal. He belonged to no one, and no side could fully claim him.

George Carlin’s American Dream is a film about a genuine renegade, who claimed no allegiances, spoke his mind freely and put his grief over hypocrisy, the inequality of the rich and the poor, and man’s inhumanity to man into his comedy. Once he figured out who he was and what he wanted to do with his quicksilver wit and love of wordplay, he opened up a whole new world of pointing out life for what it was: hard, unfair, and much too short. I miss him.

I miss my dad, too.

George Carlin’s American Dream (part 1) premieres on HBO Max May 20th, followed by part 2 May 21st.