One of Gregg Araki’s best films depicts the unexpected tenderness found in an too-often dangerous situation.

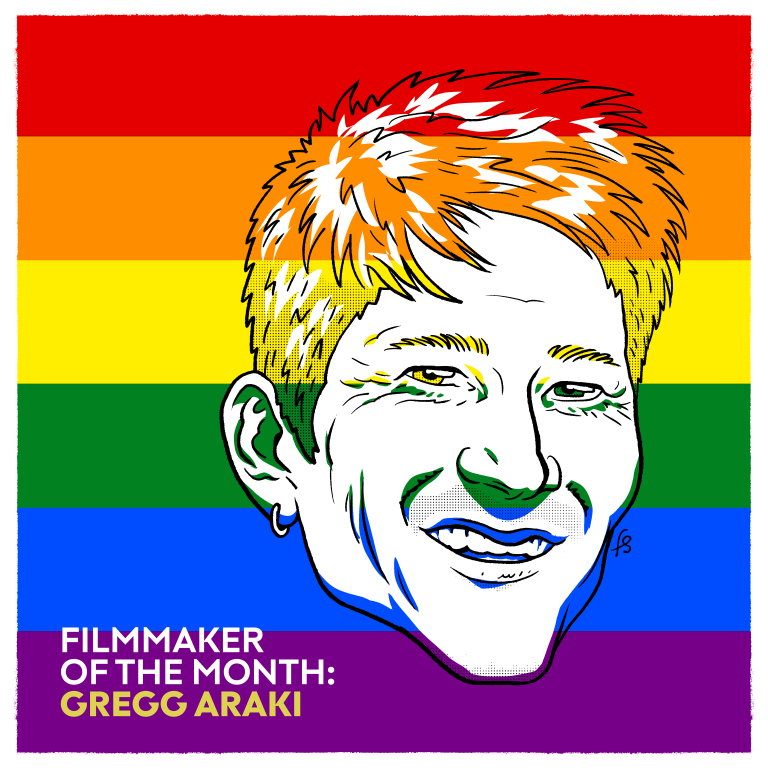

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

Coinciding with the release of a new 4K restoration of The Doom Generation, we’ve decided to turn our eyes this Pride Month on Gregg Araki’s oeuvre. In so doing, we hope to shine a light on one of the New Queer Cinema’s boldest, most radical voices.

In 2011, just after I turned seventeen, I ordered a copy of Mysterious Skin. Being online during that era, particularly on blog sites like Tumblr, meant images from Gregg Araki’s 2004 film permeated my timelines. I saw Joseph Gordon-Levitt, as gay sex worker Neil, kissing his male friend in the front seat of a pickup truck to enrage a small-town homophobe or sitting, bruised and bloodied, on the New York subway. Black and white GIF-sets of the film’s final heartbreaking scene came up regularly, the poetic closing lines quoted beneath them in italics.

To be a queer teen living in a less-than-progressive English town at that time was to find media this way, to dissect images found online and search the mentions or reblogs in the hope someone had tagged the film’s name. This gave Mysterious Skin, and those like it, a sort of cult status amongst teenagers like me and allowed directors like Araki, Gus Van Sant, Xavier Dolan, and Todd Haynes to enter my cinematic lexicon.

This searching wasn’t just about expanding my cultural horizons beyond that which was easily found (or, rather, thrust on me as a teenager in my town), but it was often about seeking language, visual or otherwise, for a queer existence and, for me, this was largely to do with sex. Being a teen in the early 00s was to have inadequate sex education generally, but specifically to maneuver a syllabus significantly lacking in any kind of queer guidance. My school was keen to stress that sex, when it did happen (though, it certainly shouldn’t), would only be between a man and woman. They did not say this outright, but implied it through the omission of any sort of gay sex education. To see, then, images of Neil with other men, to observe his confident sexuality as he lay back on the bed for his older john, was to see something that felt alien. Looking up at the ceiling, Neil’s wry smirk suggested a comfortability with sex, with being desired and desiring others that I certainly didn’t have.

Yet, to watch Mysterious Skin is vastly different than scrolling through images online. The film, based on the novel by Scott Heim, follows two boys as they grow into young adults. As children, they shared a formative experience, both being sexually abused by the same Little League coach. This unconventional bond connects the boys for years to come as their lives shape and reform around this early traumatic experience. Neil finds himself as extroverted; a bold queer outcast in a small town that he’s itching to leave. He spends his nights in the local park entering the realms of sex work as he picks up the older, often closeted men, climbing into their cars without much thought for his own safety. He remembers everything.

Brian (Brady Corbett), on the other hand, has blocked it all out. He has become convinced he was abducted by aliens as a way of explaining the hours missing from his life. This obsession masks a deeper fear of his own sexuality as Brian, in the wake of his abuse, has become almost turned off by the act of sex, refusing the advances of a girl that tries to seduce him. He’s almost sexless, whereas Neil not only finds pleasure in sex, but a profession.

Now I’m older, the images of Neil and his sex work are interestingly positioned amongst the other representations of the profession I’ve seen. It seems queerness and sex work have long been linked in the world of visual art. It’s in the soft, yet explicit paintings of New York’s pornographic cinemas by Patrick Angus, in Peter Hujar’s sleek black and white photos of hustlers at Christopher Street Pier, in the frank nude self-portraits of Annie Sprinkle, in Bruce LaBruce’s bold short films, and in Leon Mostovoy’s enthralling photos of lesbian strippers in the 1980s. Perhaps most connected to Araki’s film is the 1983 controversial series by photographer Larry Clark entitled Teenage Lust, which shows young hustlers working the streets, standing naked in their apartments, or lying in bed. Clark’s first photo series, Tulsa, focused on the teens from his hometown, but with Teenage Lust he followed the teen hustlers that had found themselves on the streets of New York City in the same way Neil does.

In contrast to how I’d long heard people talk about sex work, or how I’d seen it in mainstream films like Pretty Woman or Taxi Driver, in which it was a profession everyone was desperate to be saved from, the queer art of the late 20th century held no such view. Its outlook seemed to predate the common phrase we hear now in contemporary discussions that “sex work is work.” Just like these artists, Araki avoids any kind of moral judgement on Neil. He doesn’t suggest, as some filmmakers might, that Neil’s sexual appetite or entrance into sex work is based solely on his trauma, a narrative that would neatly explain his choices and would appease those who believe sex work is only entered into by the desperate or damaged.

For Neil, while it’s clear his tastes have been shaped by that early experience, which is evidenced by this desire for older men, it appears he genuinely enjoys his work. There’s a pride in his sexual life, an awareness of his value as an object of sexual desire in a town that seems, on the surface, sexless. He walks a certain way, with a sexual confidence beyond his years.

Araki avoids any kind of moral judgement on Neil. He doesn’t suggest, as some filmmakers might, that Neil’s sexual appetite or entrance into sex work is based solely on his trauma.

He is, however, naïve to the risks the profession poses. He doesn’t use protection, and happily climbs into the cars of men he’s never met. He carries this smalltown vision to New York City where his first client pulls off his shirt to reveal a body marked with the deep purple blotches of Kaposi sarcoma. This man, it turns out, just wants to be touched, and Neil slowly massages the man’s body under a large print of Johannes Vermeer’s 1665 painting Girl With the Pearl Earring; an image that, in this context, seems to create something timeless, as if the nameless girl of Vermeer’s painting and Neil’s life in the city share a connection, a sense of adoration from the men around them but a kind of powerlessness, too. Both Neil and the titular Girl have deep, searching eyes. She is placed alone, in a dark background and Neil, a lost boy in the city, feels the same.

Neil’s sense of feeling lost after going from his small pond to this big one is begot with a sense of confusion. To pay rent, he takes a soulless job in a sandwich shop, and it is this glimpse of a straight-and-narrow life that pushes him into the car of a stranger later that night; into a disturbing encounter with a violent man who rapes and beats Neil before throwing him out onto the street. Afterward, he rides the subway, blood smeared along his face and is caught between two lives in which his value oscillates. As an employee in the Subway-style sandwich shop he is just a number, a forgettable body that follows instructions, but in his sex work, he is desired, his youth and beauty hold an almost uncalculatable value. Almost in contrast to many sex work narratives, in which the down-and-out are forced into the beds of clients due to sheer desperation, it is the job in the sandwich shop that, to Neil, feels more like prostitution as he sells his body to a large corporation and performs mind-numbing labor over long shifts.

This is not to say sex work is idealized. It’s clear that, while Araki holds no judgement, he does not imply that it’s a job without risk and those risks are often intense and, at times, life-threatening. Most recently, shows like Pose have used the realities and dangers of trans sex workers in the 1980s and 90s to inform its storytelling, often to great effect, but they have, at other times, fallen into representing their sex worker characters as “hookers with a heart of gold,” a common trope that seems to date back to the likes of Dickens, in which their “less than ideal” profession is cancelled out by the kindness of their hearts. This can lead to narratives around sex work that err toward the moral or just. Sex work can be legitimate in the eyes of a mainstream audience if its focus is on sex workers as teachers, as motherly figures to wayward souls, or as solutions to social problems, such as in 2012’s The Sessions in which Helen Hunt’s Cheryl has sex with a man in an iron-lung, which saw Hunt receive an Oscar nomination.

Sex work being included as part of a social care system is not inherently wrong and might, in fact, offer interesting responses to contemporary issues. However, Hollywood’s continued framing of sex work within this context creates—as most political systems under capitalism aim to—a hierarchy of acceptable work. As such, it leads some to consider sex work, when done for the “right reasons” as understandable. In 2022’s sex work comedy Good Luck to You, Leo Grande the titular male sex worker addresses this head-on when he quips that his older, less progressive client might feel more comfortable if he told her he was only doing sex work to put himself through college, making his profession seem admirable only due to the fact he is striving to get out of it.

What this line of thinking avoids is someone who simply enjoys sex, like Neil and, as such, it paints them as engaging in sex work for the “wrong reasons.” While Neil and his mother aren’t rich, we never get the sense that his sex work is a means to an end. His mother works long shifts as a waitress, but there seems to be no immediate threat of eviction and no immediate financial crisis other than being working-class in America. Instead, they get by on what they’ve got. Neil’s sex work, then, is not something he’s been driven to out of necessity, nor is he acting as a sexual therapist or teacher to the men he meets.

Neil does possess these qualities, but he never uses them with his clients. Instead, his care and attention is extended to his friends, or his mother with whom he shares a strong bond. He is clearly upset with his best friend leaves their small town for New York, and, when he arrives home after being beaten, he tells his mother he was mugged on the way to the airport to spare her the worry if she knew what really happened.

His biggest kindness, however, is toward Brian, his childhood friend. By the end the film the two have reunited. Neil takes Brian back to the house their Little League coach used to live in. He is now long gone, and a new family have moved in but that doesn’t stop Neil from cracking open a window and crawling in. It’s here that Neil becomes the kind of mentor or teacher rather than in his sex work as he reveals to Brian, in detail, the extent of their abuse. The language is graphic, the descriptions leaving no room for ambiguity. When it’s over, Brian falls down into his lap and Neil gently strokes his hair as the world around them fades away.