Paul Verhoeven’s wild sci-fi action thriller remains a one-of-a-kind look at a bleak & plausible future.

“Cheaper, safer, and better than the real thing.”

That’s the promise a Rekall sales rep makes to Douglas Quaid, the hero of Paul Verhoeven’s mind-bending action rollercoaster Total Recall.

The film—which turns 30 this month—presents a future where consumers can buy memories to create the illusion of having actually experienced them. Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) dreams of visiting Mars, which has been colonized to generate resources for an ill-defined conflict between two large superpowers. An average working class guy, Quaid decides to pay a visit to Rekall to purchase a memory implant and fulfill his desires, setting in motion an absurdly violent chain of events soaked in an odd blend of blood, camp, and existential dread.

Revisiting the film provides a welcome respite from today’s CGI-engorged blockbusters and presents a bonanza for practical effects fans. It’s also trippy as hell, offering up grim satire on consumerism and the commodification of violence through Verhoeven’s trademark sardonicism.

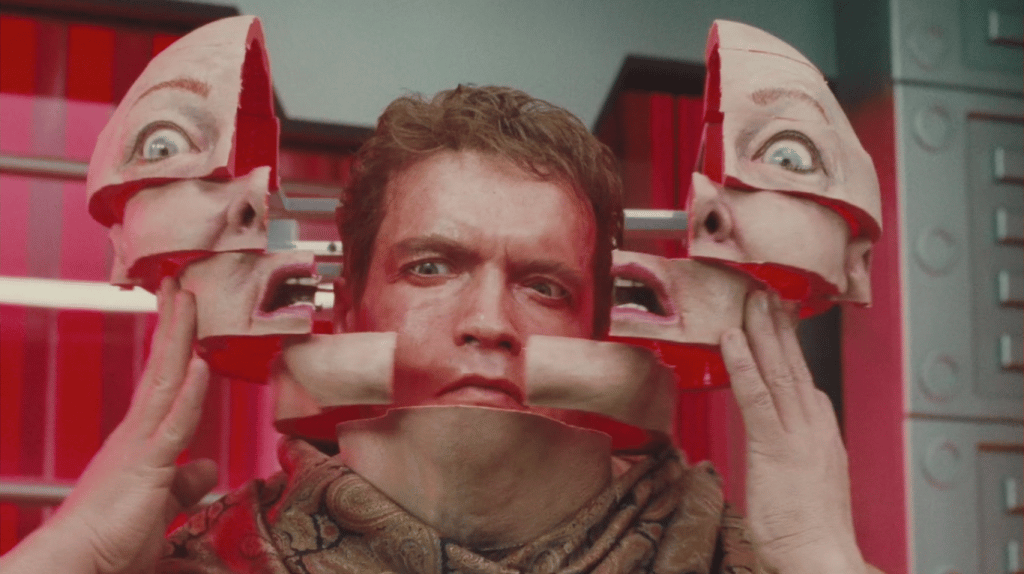

Total Recall’s gargantuan $65 million budget enabled Verhoeven to flesh out the world with elaborate, winding sets and film a variety of special effects that are simply fun to watch. Who can forget the animatronic replicas of Schwarzenegger pulling a golfball-sized tracking bug out of his nose, or violently convulsing after exposure to Mars’ inhospitable atmosphere? These machines and the ghastly make-up work of Rob Bottin (who worked on John Carpenter’s visually stunning The Thing) contribute to the film’s absorbingly tactile feel.

They also play an important part in the film’s carnival humor. The unnatural movements of the robot Schwarzeneggers are similar to those of the animatronic children on Disney’s “It’s a Small World” ride, and the film’s violence is gratuitous and stylized to the point of absurdity. On the Blank Check podcast, Griffin Newman compared the film’s patently artificial blood to strawberry syrup, which is spot on.

Revisiting the film provides a welcome respite from today’s CGI-engorged blockbusters and presents a bonanza for practical effects fans.

The production design is awesome and expansive, yet still manages to feel tacky and inauthentic, evidenced by a supposedly concrete wall that visibly bends when Quaid is pushed against it, a mere prop in an amusement park maze.

Through these stylistic decisions, Verhoeven eschews subtlety and leans into the artifice to great comic effect. He also creates a fittingly absurd space for the film’s clusterfuck narrative and its pessimistic critique of consumerism.

During Quaid’s visit to Rekall, a sales rep named Bob McClane convinces him to purchase an “ego trip,” a special package that allows consumers to “experience” their vacation as someone else. Quaid excitedly asks about the secret agent option. “I don’t want to spoil it for you, Doug,” McClane responds, “but you rest assured by the time the trip is over, you get the girl, kill the bad guys, and save the entire planet.” Swayed by description, Quaid picks it.

This boyish consumer decision is the catalyst for all the action that follows, and from the minute Quaid is knocked out to receive the implant through the final scene, the viewer is no more aware of which reality the protagonist exists in than the protagonist himself.

Shortly after waking up, Quaid violently kills four armed men who accost him because he “blabbed about Mars.” The sound effects are silly and jarring, the damp crunch of neck-breaks similar to that of crushing a large melon right next to one’s ear. A group of henchmen led by Richter (Michael Ironside) relentlessly chases Quaid through public spaces, firing indiscriminately at the disoriented hero. The collateral damage is immense, and Quaid takes part in the mayhem, at one point shamelessly using a stranger as a human shield before hurling the bloody corpse onto a group of assailants. In this film’s universe, life is cheap.

But guns aren’t the only weapons in the film. Characters subject Quaid to a constant barrage of psychological manipulation and existential gaslighting: “you’re having paranoid delusions;” “you’re not you, you’re me;” “I’m afraid you’re not really standing here right now.”

People who Quaid thought he knew turn out to be plants hired by the film’s villain, Vilos Cohaagen (Ronny Cox): first his work colleague Harry (Robert Costanzo), who leads the band of agents who attempt to murder Quaid after his visit to Rekall, and then his wife Lori (Sharon Stone), who informs him that his memories of their life together are fictional implants shortly after attempting to kill him.

It all takes a toll on Quaid, who at one point asks his Martian love interest Melina (Rachel Ticotin), “Are you still you?”

Verhoeven further complicates the hero’s sense of reality through product placement, littering major brand names amidst the gusts of violence. Enormous LED billboards tower over the drab, brutalist structures on Earth, monopolizing the film’s color while cycling through brands from Coca-Cola to Sony. The mutant sector on Mars exudes a shopping mall vibe, with a Sharper Image—the novelty electronics store—situated near the brothel where Quaid interacts with Melina and members of the Martian resistance.

According to the psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm, the constant bombardment of suggestive marketing creates “an atmosphere of being half-awake, or believing and not believing, of losing one’s sense of reality.” Quaid navigates such an atmosphere in Total Recall, his sense of self dissolving in the morass of suggestive messaging.

Televisions and newscasts hum in the background constantly, tossing more ads into the mix and reporting on violence even as it engulfs the world’s inhabitants (Verhoeven regularly uses fake newscasts and commercial spots in his movies, quite humorously in his satirical take on militarism Starship Troopers).

Quaid makes choice after choice based on the suggestive prodding of these advertisements and the news media. He broaches moving to Mars with Lori after a television report on the planet’s rebelling working class; he first considers memory implants after seeing a video advertisement on public transit; even when he finally decides to leave for Mars, he does so at the behest of a video recording of himself.

Quaid isn’t alone in having his fate dictated by external forces. Both Richter and Lori—agents in the employ of Cohaagen—are compelled into action against their will, often through video screens. Lori discusses her loathing for Mars multiple times, expressing dismay that she has to travel to the planet on her boss’ orders. Cohaagen treats his subordinate Richter like a punching bag, ruthlessly cutting him down for repeatedly failing to capture Quaid.

Cohaagen and other authority figures talk in the imperative: “keep still, fighting just makes it hurt,” a doctor tells Quaid; “don’t think, just do it” Cohaagen tells Richter repeatedly. But these authoritarian directives are filtered through Verhoeven’s dark sense of humor. When Cohaagen contacts Richter via video phone in one scene, he begins the call with his head turned, twisting around like a model in a hair product commercial before histrionically barking his commands.

Verhoeven’s comical tone encourages the audience to laugh during the film’s overblown and often preposterous violence. But combined with the barrage of advertisements and mind-twisting antics of the script (penned by Alien screenwriters Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon, along with Gary Goldman), the director’s cynical brand of violence stultifies and desensitizes as much as it entertains, providing a rather morbid reflection on how mass media impacts our understanding and acceptance of violence in our own world.

Consider advertisements on Twitter selling IOS games that involve mowing down zombie hoards in a post-apocalyptic hellscape sandwiched between news reports of overflowing morgues in New York City and political leaders prematurely lifting restrictions related to COVID-19. We are inundated with stories of implicit violence meted out by an uncaring elite, overwhelmed by the knowledge of events while they directly impact and permeate our daily lives.

By the end of the film, Quaid wins Melina’s affection, kills Cohaagen and his lackeys, and saves the downtrodden population on Mars. But Total Recall concludes with a final expression of self-doubt.

“I just had a terrible thought. What if this is a dream?” Quaid says to Melina.

Quaid can be forgiven for his confusion. In retrospect, it turns out that McClane’s sales pitch for the ego trip package perfectly describes the film’s end.

In a world where sales reps are prophets, authenticity is hard to come by.