Every month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema, and the filmmaker’s own biography. For April, we revisit both the game-changing hits and low point misses of Francis Ford Coppola. Read the rest of our coverage here.

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 coming-of-age drama The Outsiders, adapted from S.E. Hinton’s classic novel by the same name, is a dreamy, soft endeavor. Despite the gritty world in which the film’s protagonist Ponyboy Curtis (C. Thomas Howell) exists, the film is a surprisingly sweet, earnest and vulnerable in a way that from some angles could be considered cloying, but ultimately succeeds in capturing the overwhelming and all-encompassing emotions of adolescence.

Howell’s Ponyboy is a tender-hearted and kind teenager born into a family of Greasers — a working class gang on the wrong side of town in 1960s Tulsa, with two older brothers. He’s proud of where he comes from, and willing to stand up to the Socs (pronounced Soshes, short for “social”), a rival gang of affluent bullies. Ponyboy’s life is changed forever one night when his friend Johnny (Ralph Macchio), also a gentle soul, inadvertently kills a drunk Soc who’s trying to drown Ponyboy, and they must flee town to avoid arrest.

Coppola was inspired to make the film in 1980 during the troubled time following the financial disaster of One From the Heart. He received a letter from Jo Ellen Misakian, a librarian at the Lone Star School in Fresno, California and parent to a teenage son, who had decided that The Outsiders would make an excellent film and collected hundreds of signatures from young people who supported the idea.

As recounted in a 1983 article in the New York Times following the release of the film, Misakian contacted Coppola by looking up his address in the reference section of the library. In the letter, she described the school and its students and included a copy of the paperback “because [she] knew he wouldn’t go out and buy it.”

Normally, a letter like this would not have reached someone at Coppola’s level, nor would it have been something that could ever have been seriously considered. Luckily, Misakian caught Coppola at the perfect moment and sent it to his New York address instead of his Hollywood address, which helped it stand out. Fred Roos, Coppola’s producer, read the book and agreed that Misakian and the kids were onto something. “It was signed by like 110 little signatures,” recalled Coppola about the letter in a 2005 interview with Today. “Who can ignore that?”

The filmmaking process was cathartic for Coppola, who considered the opportunity a chance to escape from his financial problems and allowed him to “be a camp counselor” again, with a young cast and crew. And it was indeed a fun set — in a 2018 oral history of the making of the film, the members of the cast recall the legendary pranks that took place on set, of which there were many.

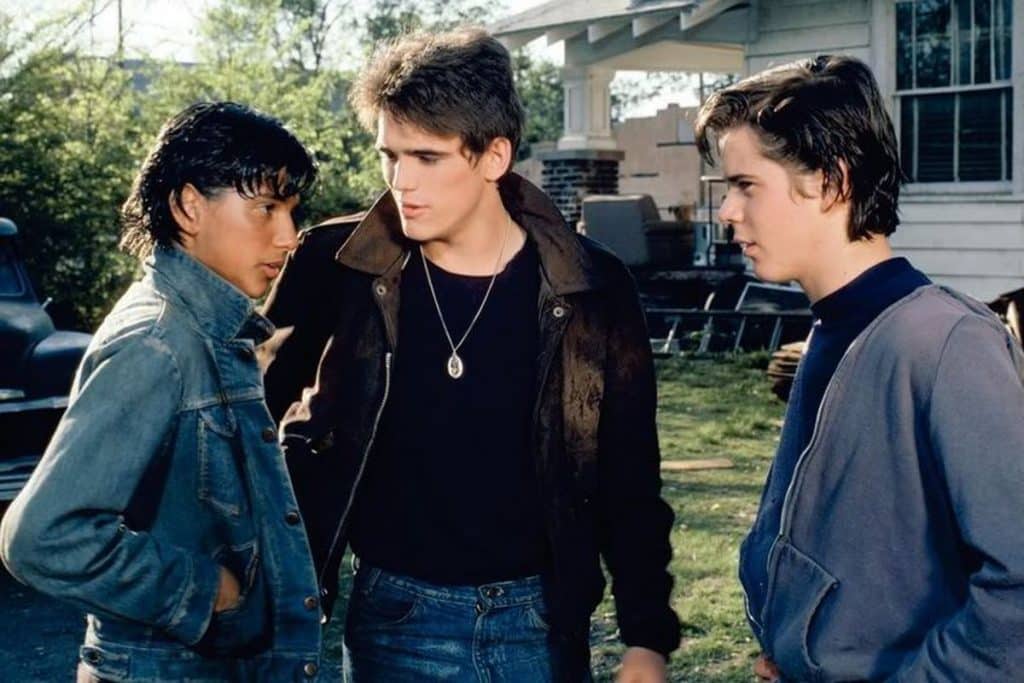

The opening credits of The Outsiders contains a seemingly endless list of future stars, including Patrick Swayze, Matt Dillon, Rob Lowe, Tom Cruise, Emilio Estevez, and Macchio, the so called “Brat Pack”, as they would later be dubbed by New York Magazine in 1985. But in 1983, the Brat Pack was not yet a term that existed, and similar to a film that would come decades later – Short Term 12, which launched the careers of Brie Larson, Kaitlyn Dever, Rami Malek, Lakeith Stanfield, and Stephanie Beatriz, The Outsiders functions as a fascinating time capsule of the nascent phase of these actors, especially a captivating young Diane Lane, who plays Sherri “Cherry” Valance, a preppy student whose Soc boyfriend is the one who gets killed by Johnny.

After Ponyboy and Johnny flee Tulsa, they hide in an abandoned church for several days, where they try to disguise themselves — Ponyboy by bleaching his hair blond, Johnny by cutting his hair shorter — and afterwards, stare, displeased at their altered reflections. “It’s like being in a Halloween costume you can’t get out of,” Ponyboy complains, and the fact that this, of all things, is what he chooses to fixate on, reveals the depth of his naivete, and the pathos of the narrative.

The Outsiders…ultimately succeeds in capturing the overwhelming and all-encompassing emotions of adolescence.

Realistic the film is not; with heightened dialogue and cinematography that uses a Hollywood vernacular that “went out of fashion at least 20 years before the picture was even made” to evoke the turbulent emotions of youth onto a “giant canvas”, as Sean Burns mentions in his 35th anniversary retrospective on the film, The Outsiders has the oversized heart of a stage play with the visuals of a painting. “You two are too sweet to scare anyone,” Sherri says to Ponyboy and Johnny, and truly, it’s hard to believe that two young men who have grown up in such rough circumstances could actually be so soft.

But the tenderness between young men who don’t know where their lives are going but who trust in each other is the thread that runs throughout the film, not just for Ponyboy and Johnny, but also for Patrick Swayze’s Darrel “Darry” Curtis, an older brother struggling to fill the shoes of absent parents, and Matt Dillon’s Dallas “Dally” Winston, a juvenile delinquent with rough edges who really only cares about one person — Johnny — and is unable to cope when Johnny succumbs to burn injuries after saving children from a fire at the abandoned church.

Ultimately, the heartfelt performances from all the young actors is what allows the film to hold up, despite the melodramatic sensibilities of the cinematography; particularly in the scene when Johnny and Ponyboy watch a beautiful sunset. “The mist is what’s pretty, all gold and silver. Too bad it can’t stay like that all the time,” observes Johnny, and in response, Ponyboy quotes the Robert Frost poem “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” It’s a scene that could have easily come across as insincere, but thanks to Howell and Macchio’s genuine, vulnerable performances, Johnny’s dying wish is for Ponyboy to “Stay gold,” at the end of the film feels heartbreakingly authentic.

Described in his own words as “a Gone With the Wind for 14-year-old girls”, Coppola’s adaptation of The Outsiders is soft but not subtle, but that’s what makes it work. Ponyboy’s story isn’t high art; but it isn’t trying to be — and in the end, it finds poignancy in big feelings and the honest vulnerability of youth.