Gregg Araki’s collection of vignettes takes the glossy, audience-friendly shine off queer love in the modern world.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

Coinciding with the release of a new 4K restoration of The Doom Generation, we’ve decided to turn our eyes this Pride Month on Gregg Araki’s oeuvre. In so doing, we hope to shine a light on one of the New Queer Cinema’s boldest, most radical voices.

It’s been interesting to follow the reception of teen movies from the 1980s and 1990s has changed in the decades since. Some, like Clueless and The Breakfast Club have endured as classics. Others are better left forgotten. Of these, many are victims of a sameness of perspective. In other words, many of them are built on cis, straight, and usually white protagonists, and have little to offer people from different demographics.

With 1993’s Totally F***ed Up, Gregg Araki, a major member of the New Queer Cinema movement, offers his own take on the John Hughes mode. It’s an abrasive, thrilling, funny, sexy, and compelling film that follows a cadre of queer teens in Los Angeles. Rather than a singular narrative, it’s a series of fifteen numbered vignettes

tracking a cohort consisting of Andy (James Duval), boyfriends Steven (Gilbert Luna) and Deric (Lance May), lesbian couple Michele (Susan Behshid) and Patricia (Jenee Gill), and Tommy (Roko Belic). Throughout Araki’s chronicles their misadventures, traumas, sexual escapades and romantic entanglements, as the six characters offer their perspective and experiences.

Totally F***ed Up has the feel of a documentary or video essay, albeit nominally fictional. The vignettes are unapologetically heavy, delving into AIDS, heartbreak, gay-bashing, and homophobia. Simultaneously, at barely

80 minutes long, it maintains a quickness and lightness of touch. It isn’t apandering Oscar drama about how traumatic it is to be queer. It’s the lives of these young queer people, the joys and troubles that come with being alive.

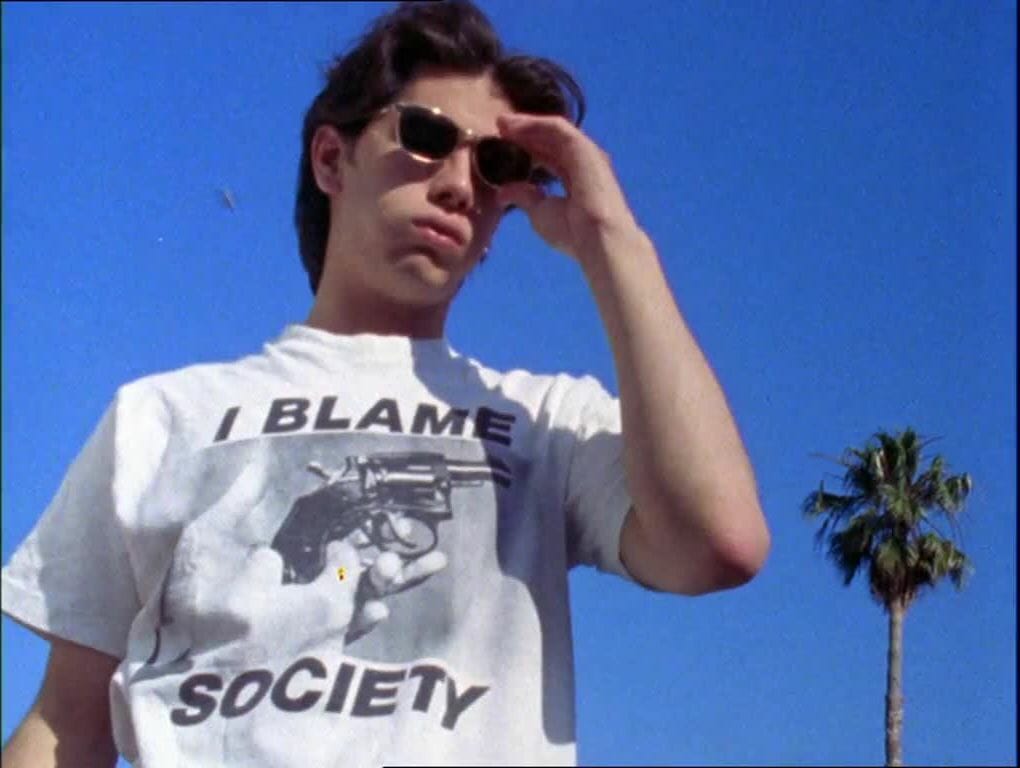

Araki employed guerilla filmmaking, with a shoestring budget, a team of young, hungry, unknown actors, a handful of crew, and operated the camera himself. The result is a very endearing analog look, born from sans-permit location shooting and grainy film. Totally F***ed Up, like many indie films of its era, makes one nostalgic for a more tactile cinematic era. When comparing this and Araki’s other early 90s masterpiece The Living End to contemporary queer cinema, the loss of messiness and imperfection is tangible. Araki’s guerilla filmmaking builds in an inherent sense of passion and urgency, as if the moment had to be captured right there and right then with whatever tools they could scrounge up. Studio releases and streamers definitely do not have that

feeling, and even indie films don’t look this post-punk. In looking at 21st century queer movies like Do Revenge (2022), The Boys in the Band (2020), and Love, Simon (2018), they look glossy, fashionable, and palatable–with glimpses of queer anarchy that feel all but manufactured.

In addition to its emotional honesty and guerilla craft, Totally F***ed Up also serves as Araki’s tribute to Jean-Luc Godard. It directly references Godard’s 1966 film Masculin Féminin: 15 faits précis (or Masculine Feminine: 15 Specific Events). Indeed, the homage is quite direct, both in format and in title. I wouldn’t say that Araki’s film is a modern update or a “queer version” of Godad’s classic. But by wielding the New Wave master’s modes, Araki provides space for a demographic to speak their truths and tell their story. Godad’s films are often essays, especially movies like Vivre sa vie (To Live Her Life) and 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle (2 or 3 Things I Know About Her), which capture political and socioeconomic fervor of their time.

Totally F***ed Up functions the same way—its characters and their stories are important, but they also tell a wider story about a generation, a moment in history, and the angry restlessness of youth who live in both freedom and oppression. Moreover, on top of its exquisite drama, Araki’s direction is stunning. A late film sequence captures a homophobic attack via a series of dreadful fades in and out. Sex scenes are both erotic and urgent, filmed with abandon and intimacy.

Araki’s later films, his masterpiece Mysterious Skin (2004) especially, find the subtle truths and nuanced emotions around intense subject matter and narrative choices. Totally F***ed Up stands as an early example of his ability to seamlessly bring together an era’s top issues, the camaraderie and prickliness of youth, and low-budget style to create a singular cinematic experience. Totally Fed Up may call itself “another homo movie,” but there were few like it before it, and even fewer like it since.