Read also:

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableScott Derrickson keeps a silly premise above water thanks to a fast pace & a creepy villain turn from Ethan Hawke.

Gather around, children, and let Auntie Gena tell you a story about days gone by. Long ago, up till around 1984, kids used to run free in the streets from dawn till dusk, with virtually no adult supervision. Was it a better time? Not really, just different, and it all came to an end with the collective belief that bad things happen to children who aren’t carefully watched at all times. Now it’s swung so far in the other direction that allowing your children to walk themselves to school may result in a visit from child protective services. Scott Derrickson’s The Black Phone takes place in the time before, when parents didn’t worry about monsters until they were almost under their noses.

Based on Joe Hill’s short story of the same name, The Black Phone takes place in a Boulder suburb where adolescent boys have gone missing, but no one except the police seem all that concerned about it. Finney (Mason Thames, who could be Stranger Things’ Finn Wolfhard’s younger brother), bullied and living with his tough as nails younger sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) and drunk, abusive widower father (Jeremy Davies) is more or less oblivious to it as well, until one of his friends disappears. Then, Finney himself is taken, just snatched off the street like a couch left on a curb.

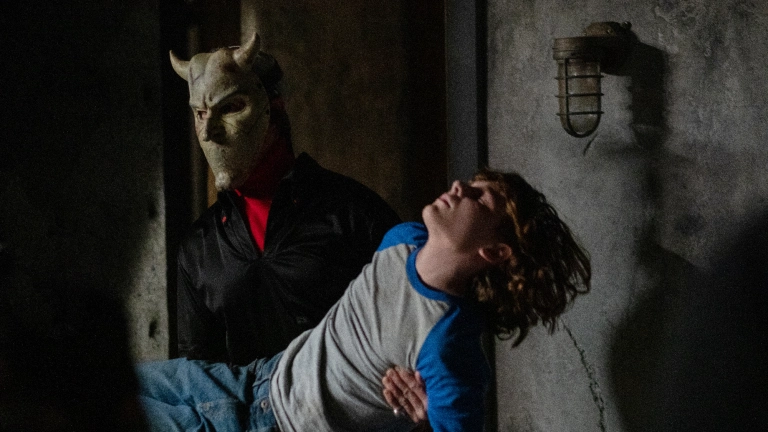

His captor is known only as The Grabber (Ethan Hawke), who wears a creepy devil mask with removable parts that make him look as if he’s either leering or frowning. The Grabber keeps Finney in the dank basement of his house, with only a mattress and a filthy toilet, taunting him with both promises to let him go, and promises to do him harm. “I’m gonna make it really hurt,” he hisses at one point, all but daring Finney to try to escape. Meanwhile, back at home, Gwen, who’s already been having dreams about the other missing boys, begins dreaming about Finney as well, and what horrors may await him.

Along with the mattress and the filthy toilet is the titular black phone, which The Grabber insists doesn’t work, and indeed is disconnected. It still rings, though, and when Finney answers, he’s given a series of clues from [REDACTED] on how to get out of the basement before he meets the same fate as The Grabber’s other victims. Finney, a very resourceful boy despite being so meek he doesn’t try to fight back when bullies beat the everloving crap out of him, takes these various hints and works to set himself free, before The Grabber wins the “naughty boy game.”

Admittedly, a boy trying to set himself loose from a kidnapper/murderer with the help of a magic phone is a pretty silly premise. I’ve read 20th Century Ghosts, which featured the short story it was based on, but it was a long time ago and I don’t really remember if it seemed less silly on paper. And yet, somehow it works. It’s less horror and more of a suspense thriller, as we watch Finney try to work with the clues he’s been given, in a one-person escape room challenge. Only when Hawke is on screen do the horror aspects really come into play. Despite never playing a villain before (unless you count his loathsome character in Reality Bites), Hawke really makes a meal of his role. Because he’s masked for almost the entire film, much of the work is in his voice, weird and almost sing-songy, and never having to get loud to have an unnerving effect. His almost friendly affect while bringing Finney food is, like Kathy Bates in Misery, even creepier than when he eventually snaps.

Comparisons to It are both inevitable (because of who Joe Hill is related to), and valid. The Black Phone’s small town of the past setting, psychotic bullies, and a cackling child murderer with balloons are all reminiscent of the earlier film, while not quite reaching its level of visceral scariness (let alone the book’s). Both movies are also poignant in their portrayal of children bonding together in the face of evil – here it’s Finney and Gwen, who, when her dreams become more vivid, sets out on her own to rescue him, just as she’s rescued him from danger before.

What doesn’t really work is the film’s all-too-frequent reliance on Gwen, maybe 10 or so, letting loose with a string of profanities that would make a sailor blush as a cheap moment of levity (though the audience I saw it with loved it, so what do I know?). Even in the less paranoid era of the 1970s, it’s a bit implausible that The Grabber would be able to get away with his misdeeds as long as he has, living in the same small town as where he kidnaps his victims, without a single person seeing anything. Plausibility stretches to the breaking point with the third act reveal of a somewhat superfluous character who’s closer to what’s happening to Finney than anyone realizes.

That being said, no one goes to a horror movie for realism, and the positives of The Black Phone outweigh the negatives. Capturing that odd sort of hazy beige of the 70s (a lot of the scenes look like fading photographs), it emphasizes that moment of time when adults and children, even those in bucolic suburbia, were faced with a horrifying truth: the most dangerous people were often right in their own backyards.

The Black Phone opens in theaters June 24th.