It’s hard not to weep for the movies after the year we’ve had. The COVID-19 pandemic has slammed people and economies with equal ferocity, and few industries have been harder hit than the cinema. Theater chains have closed for good; major studio releases are being shunted to streaming, where affordability and access come at the cost of a loss of spectacle, and diminished compensation for the hardworking people who make them. Most of the great movies we’ve seen this year were on the small screen. Not even Christopher Nolan could save the theatrical experience in 2020.

That said, even within this new normal, the world of the cinematic arts has paradoxically never felt more vibrant. Each new release felt like a gift, whether fabulous or flop. Even if we had to watch it on our couches, the fact that it came to us at all felt like a small miracle. We may not be able to see movies in a crowded theater, to feel the collective energy of dozens of people directed at the same object of art blown up as big as God. But the art came to us anyway, and absent the church-like awe of the theater, we still found ways to connect through it.

Streaming services like Netflix, Amazon, and HBO Max became our new multiplexes, the home for big-budget spectacle and indie darlings alike. Funny enough, 2020 gave smaller releases a bigger chance than ever to capture the collective consciousness, given studios’ initial reticence to dump $100 million blockbusters into our Rokus and Chromecasts. We weren’t going out to see Black Widow; we stayed inside to watch Palm Springs. We gave Spike Lee two chances to wow us, and he didn’t disappoint. Hell, Steve McQueen gave us five masterpieces in a single month. We paid more attention to documentaries than ever before, and subsequently realized that hey, a lot of great docs came out this year.

While movies may be in danger, that just makes it more necessary than ever to talk about, and share however we can, the ones we love. In that spirit, here we present twenty-five of the best films of 2020 — no rankings, no scores, just a shortlist of the best cinema the year had to offer. We hope you take the time to catch up to them while you, like us, wait for a vaccine so we can one day bask in the glow of the projector together again.

(Sidenote: I also want to take this moment to thank each and every one of The Spool’s readers, writers, and editors, and everyone who makes the site possible. This is the end of our first full, actual year of operation, and in such tumultuous times, I’m immensely grateful for every single person who’s contributed to these pages and designed to read them. Hope to see you on the other side of 2020.) [Clint Worthington, editor-in-chief]

HONORABLE MENTIONS: Sound of Metal (Amazon), Palm Springs (NEON), Babyteeth (IFC Films), Beanpole (Kino Lorber), Host (Shudder), Dear Comrades! (NEON), Selah & the Spades (Amazon), La Llorona (Shudder), Birds of Prey (WB), Swallow (IFC Films), The Forty-Year-Old Version (Netflix), Gunda (NEON), Mucho Mucho Amor (Netflix), Possessor (NEON), Bacurau (Kino Lorber), The Vast of Night (Amazon), Miss Juneteenth (Vertical Entertainment), One Night in Miami… (Amazon), Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (Netflix), Let Them All Talk (HBO Max)

The Assistant

After Ukraine Is Not a Brothel and Casting JonBenet, Kitty Green makes her first scripted feature in one of the year’s very best. Julia Garner plays Jane, a Northwestern University graduate and aspiring film producer. Now she works as an office assistant for an industry executive. She does the work one would expect her, but it’s over the course of a day that she becomes aware of the predation going on. Comparisons to Harvey Weinstein have already been made, but to relate the two is to simplify the issues on screen here.

It’s brutal in how it sees the widespread acceptance of rape culture. It also leaves a mark thanks to Green’s ability to borrow from Chantal Akerman and turn-of-the-millennium Gus Van Sant. Green, who co-edited with Blair McClendon, keeps the pace methodical. There’s such an attention to detail that makes even the most menial transfixing: the blocking, static shots, and symmetry constantly feed the viewer with new information until the environment becomes fully formed. The Assistant is one of the most effectively low-key movies in quite some time, one that allows Garner to demonstrate just how sterling of a performer she is. [Matt Cipolla]

Black Bear

A movie about gaslighting that also manages to gaslight the audience, Lawrence Michael Levine’s Black Bear is unexpectedly, deeply unsettling. What initially starts out as tedious mumblecore about a couple whose shaky relationship is tested with an arrival of a quirky guest at their AirBnB becomes something far more different and compelling, almost a psychological thriller about a tyrannical filmmaker who emotionally torments his wife/lead actress in order to get the best performance out of her. Aubrey Plaza is astonishing in a dual role, calmly smirking with malevolent glee in one scene and near-feral with anger and sorrow in another. Black Bear isn’t an easy or fun film to watch, but the sheer effort Plaza puts into it deserves a large audience. [Gena Radcliffe]

Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

Some viewers will never look into the backstory of The Ross Brothers’ non-fiction/fiction hybrid, Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, and come away with feelings of unmitigated loss about “The Roaring 20s”. The reality is more complicated, and some have felt cheated in the film’s presumption of truth in showing the end of a hole-in-the-wall Nevada bar while surveying the regulars and tumbleweeds who make their way in for one or a dozen of drinks. Nudged but not orchestrated, observed but not mediated; this is an experiment whose selective honesty makes its nuggets of purity all the more real. A bittersweet distillation during the credits with its gallery of stills, this portrait is nostalgic, but the details aren’t as romantic as patrons nod off mid-sentence and fights erupt. This is an Irish Wake, and even if it might not have the energy of a celebration, The Ross Brothers make a powerful case that everyone is where they should be at that moment. [Michael Snydel]

Da 5 Bloods

The first of two Spike Lee movies (and two of his best) in 2020 couldn’t have picked a more tragically appropriate time to premiere: a mere two weeks after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, a move which sparked a resurgence in the Black Lives Matter movement and a reckoning with the white supremacist systems America has soaked itself in. Yet despite its Vietnam setting, Da 5 Bloods feels like a reckoning of its own. Lee, in his long-standing role as cinematic reclaimer, de-colonizes the Vietnam war movie for his story of the Black soldiers who fought and died in a senseless war. It’s a film indebted to the war films of the ’70s, yet infused with complicated, contemporary anger at how little things have changed since then. And it’s anchored by a supporting turn from Chadwick Boseman (a role that would prove tragically prophetic) and a fire-and-brimstone Delroy Lindo in a role that should be ignored at your own peril. [Clint Worthington]

Dick Johnson is Dead

The funniest movie of 2020 is a documentary chronicling a former psychiatrist’s battle with dementia. No, wait, hear me out. Cinematographer Kirsten Johnson offers an extraordinary eulogy for her father, filming him “dying” in a series of slapstick accidents, and portraying his vision of Heaven, which involves endless chocolate fountains and popcorn falling from the sky like rain. Johnson somehow manages to maintain a perfect balance of love, humor, and respect without ever coming off as flippant or insensitive — there’s a scene during a funeral that will make you literally both laugh and cry at the same time. We should all be able to accept love and loss with this kind of clear-eyed joy. [Gena Radcliffe]

Driveways

We lost the great Brian Dennehy this year, and it’s hard to think of a swan song more fitting and delicate than Andrew Ahn’s sorely-underappreciated Driveways, one of the most intimate character studies of the year. Much like fellow best-of recipient Minari, Driveways tells the story of American life through the eyes of a young Korean-American child (Lucas Jaye) with stunning gentleness and poignancy. The film’s subtle, almost to a fault, but that’s what makes each little gesture from Jaye, Dennehy, and Hong Chau stand out all the more. It’s a film concerned with the ways loneliness can be shattered with the right person in the right moment, which is the kind of humanism 2020 could have used a lot more of. [Clint Worthington]

Emma.

Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, has come to the screen before; like quite a few of Jane Austen’s heroines, she’s a Hollywood natural. But Autumn de Wilde’s Emma., unnecessary punctuation and all, is every bit and handsome and clever as its protagonist. In concert with the marvelous Anya Taylor-Joy, de Wilde and screenwriter Eleanor Catton capture the porcelain perfection of Emma’s coddled, cosseted existence in with a film that only gets more bewitching as the edges begin, ever so slightly, to fray. Many Austen adaptations fail to capture either the sharp wit or soft underbelly of her work, and fewer still capture both. Put this Emma. on the shelf alongside Ang Lee’s Sense & Sensibility and Amy Heckerling’s Clueless, among the greats where it belongs. [Allison Shoemaker]

The Father

There’s always a hesitation in a play being adapted for the screen, and the compromises that come with that translation. Adapted and directed by the source playwright, Florian Zeller’s The Father is a rare exception to these qualifications. Led by a galvanizing, and yes, monologue heavy, Anthony Hopkins performance (and indispensably supported by a crushing Olivia Colman performance), this isn’t only a showcase for two of the best actors of this generation to emulate the chaotic paradox of Dementia, but a film in thrall to its own thematic uncertainty. That may suggest Charlie Kaufman or other metaphysical cinematic fiddlers. Zeller’s inflection points are largely more mundane whether they’re visual — an errant chair, painting — or in platonic misunderstandings, but that’s far from suggesting this feels perfunctory. If anything, Zeller feels preternaturally in tune with the relationship of familiar spaces and people. All the world’s a stage and this apartment is the nexus of a great tragedy. [Michael Snydel]

First Cow

Delicious pastries and cute animals dominated the (far too short) discourse surrounding Kelly Reichardt’s reliably excellent First Cow, but beneath the flaky surface of the most traditionally entertaining film in her career rages another story about the ravages of capitalism and its illusion of promise. Headed by career-making performances from John Magaro (hapless but soulful) as Cookie, a baker whose gruffness stands in stark contrast to his gentle demeanor; and Orion Lee (Quietly confident) as King-Lu, an enterprising farmer quick to adapt; this is a film in constant dialogue with expectations of the time whether they be cultural, social, and economic, and filtered through Reichardt’s extraordinary eye for the ordinary. Struggle propels these two and their greatest desires are a small piece to call their own – a sentiment that’s beautifully underlined in not only Cookie’s magnanimous relationship with the cow as an extension of his goals but also King-Lu’s diligent sweeping of their home. A taste of civilization, indeed. [Michael Snydel]

I’m thinking of ending things

Charlie Kaufman doesn’t have a perfect track record, but that comes with bountiful ambition. Of course, that also means that something so bewilderingly great could come up at any moment. Enter I’m Thinking of Ending Things, Kaufman’s first film in almost five years, which, based on Iain Reid’s novel, seemingly follows everything and nothing. Sure, it’s about an unnamed young woman (Jessie Buckley) as she contemplates breaking up with her boyfriend (Jesse Plemons), but it’s so much more than that.

An exploration of social anxiety, a dive into the subconscious, a look at mortality—its dream logic binds it together finely and loosely. Lukasz Zal’s cinematography is both frigid and warm. Robert Frazen’s editing makes its surrealist horror touches as slick as can be. Supporting roles from Toni Collette and David Thewlis blur the line between humor and melancholy, and with Kaufman’s script, even 20-minute dialogue scenes in the front seat of a car fly by. It’s absolutely transfixing. [Matt Cipolla]

The Invisible Man

As metaphors go, it’s difficult to imagine one more potent than the invisible man of Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man. It’s not subtle, at least in this respect, and is not meant to be: abusers hide in plain sight, sometimes so well that not even their victims fully grasp what’s happening. That’s where the first of two excellent Elisabeth Moss-led films begins, but its exploration of the insidious nature of abuse doesn’t stop there. It’s also a cracking good horror movie with several thrilling set-pieces, including an early break for freedom from Cecilia (Moss) and a terrifying fight in an ordinary and ordinarily peaceful home. But Whannell’s masterful tension-building wouldn’t hit quite so hard without that metaphor and Moss’s fearless performance. All that, and a few good jump scares, too. [Allison Shoemaker]

Minari

Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari is, at its heart, the story of the American Dream, and what happens when people come to America to find it, only for the fates to have other ideas. Drawing loosely from his own life, Chung renders a young Korean-American family with painterly brushstrokes, including Steven Yeun in an awards-caliber turn as a frustrated father torn between expectation and ambition and Youn Yuh-jung as the family’s scene-stealingly crass grandmother). Like Driveways, it’s a story about Asian-American identity that doesn’t dwell on racial difference or animus; rather, Minari treats America like a truly wild frontier, one as willing to give as it is to take. Poetic, heartfelt, and as bittersweet as the resilient weed from which the film takes its name. [Clint Worthington]

The Nest

Sean Durkin’s long-awaited followup to 2011’s Martha Marcy May Marlene is a seething, tension-filled family drama more akin to a horror movie than the works of Mike Nichols. And yet, there’s a flair of the theatrical in the cast’s layered, intimate performances, particularly Jude Law and Carrie Coon as a fragmented couple whose move to London threatens to crack open existing fissures even further. Coon is magnetic as the slowly-unraveling wife suffocating under her trophy-wife expectations, while Law’s boyish features reveal the resentful child underneath his rich, successful facade. Amid the dark corners and cavernous rooms of their too-large Surrey estate lies ink-black resentment for each other and a world they don’t belong to, which is what makes The Nest so absolutely involving. [Clint Worthington]

Never Rarely Sometimes Always

On the surface, Eliza Hittman’s latest is about Autumn (Sidney Flanigan), a 17-year-old Pennsylvania girl traveling to New York City with her cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder) to get an abortion. That’s a crucial part of it; that doesn’t mean that’s the only part, though. A complement to Hittman’s previous film, Beach Rats, where Never Rarely Sometimes Always soars is in its exploration of the female gaze. It’s the bond between these two girls that drives the film even through its darkest, quietest moments.

This is Flanigan’s first-ever role, yet she’s at once meek, confident, and analytical of her surroundings. She has that special sort of connection with Ryder, the one where words aren’t always necessary. With Hélène Louvart reteaming with Hittman to shoot the film on gorgeous 35mm, this one doesn’t treat Autumn like a character. It treats her like her own person, never pushing her in any one direction. From her decisions to her demeanors to what she reveals to others, the movie follows her agency, even if others have put her in less than desirable circumstances. [Matt Cipolla]

Nomadland

In just a handful of films, Chloé Zhao has marked herself as one of cinema’s foremost chroniclers of the American Midwest; her latest, Nomadland takes that understanding further than its ever gone before. Her documentary-like camera hovers around Frances McDormand’s Fern, a widow who’s reconfigured her life to spend it among the nomadic communities of the heartland’s RV parks and itinerant communities. Zhao douses Fern in the sumptuous colors of dusk, lending grandeur to her lonely life of cramped conditions and driving. And yet, despite its rootlessness, we see why she might not want to ever leave. As much a celebration of American freedom as it is an indictment of the economic conditions that make such lifestyles necessary, it’s a staggering piece of work. [Clint Worthington]

On the Rocks

For her seventh feature (eighth if you count A Very Murray Christmas), Sofia Coppola pivots towards something more accessible on the surface. Laura (Rashida Jones) is a New York writer who suspects her husband, Dean (Marlon Wayans), is cheating on her. Soon after, she and her dad, Felix (Bill Murray), begin to tail the suspect, ostensibly letting wacky hijinks ensue. And they do ensue, but not so much in the traditional sense.

On the Rocks is a screwball comedy, but it’s a screwball comedy because it’s following New York’s lead. Coppola’s characters spar with dialogue that’s overt in a way that functions as both parody and tragedy and, in spite of its lighter moments, that’s what it is: a tragedy. It’s easier for Laura to live in blissful ignorance, and the movie reflects that in how it engages its audience. Some may see the movie as “cute” or “slight,” but that’s at first glance. There’s more to it than that. It might be minor work for the queen of ennui, but even that’s really good—unlike Laura and Dean’s marriage. [Matt Cipolla]

Promising Young Woman

Few movies understand the rage that comes from trauma, but Emerald Fennell’s Promising Young Woman is one hell of a debut with one hell of a hook. Years ago, Cassie (Carey Mulligan) lost her lifelong friend, Nina, to a trauma. Now Cassie’s dropped out of med school, working at a coffee shop and living with her parents. In her spare time, she goes to clubs, waits for “nice guys” to try to take advantage of her, and then teaches them a lesson. It’s a fantastic, fresh twist on the rape-revenge tale that tempts comparisons to the likes of Ms .45, but this approach is different than most.

What sets this apart is that not once does Fennell’s script see Cassie as impulsive, crazy, or close to the deep end. Mulligan and Fennell show a fully formed person. Her life was forever changed by rape, and others don’t understand it because it’s impossible to fully grasp unless you personally know it. There’s a moral grey area throughout that’s cathartic and hopeless, darkly hilarious and disturbing, and with its production design and costumes, the final result is addictive. Finally, it’s okay to be enraged. Finally, someone gets it, and they don’t care what you think. [Matt Cipolla]

She Dies Tomorrow

Though she couldn’t possibly have predicted the events of 2020, writer-director Amy Seimetz’s cosmic horror She Dies Tomorrow is all too chillingly of the moment. A virus of sorts spreads throughout a town, one that convinces its victims that they’re going to die the next day, how and under what circumstances it’s unclear, but inevitable. Despite the checking off of personal bucket lists and saying what long needed to be said, nobody in She Dies Tomorrow finds peace in the idea of death, just isolation and loneliness. It’s unique, disturbing, and unforgettable. [Gena Radcliffe]

Shirley

Josephine Decker’s Shirley shouldn’t really be called a biopic. First of all, it’s largely fictional, and that’s not the work of aggrandizing historians or diligent publicists—it’s actually fictional, as in it is a work of fiction that happens to center on a real person. But more importantly, it’s a film with no interest in the typical trappings of a portrait-of-the-artist film. Instead, it’s more akin to something likeWho’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, only Elisabeth Moss and Michael Stuhlbarg are each both Martha and George, and the undercurrent of psychosexual horror isn’t so under. It’s a feral little movie, and thanks to Moss’s snarling yet somehow meditative performance, it’s one that’s likely to linger when many other great-artist films fade. [Allison Shoemaker]

Small Axe: Lovers Rock

The second movie in Steve McQueen’s ambitious Small Axe anthology, Lovers Rock is proof that your movie doesn’t have to be about anything specific to hold the audience’s attention. It doesn’t even have to have a discernible beginning, middle or end. It just has to be, and in this case it’s an exhilarating, almost documentary-like look at a raucous dance party held by a group of West Indian teens in late-’70s working class London. Though there are hints of the racism and hard lives they lead, much of Lovers Rock takes place on the dance floor, where there’s not a care in the world. Every period detail is “you are there” accurate, and if you don’t find yourself wishing you actually were, you might be dead on the inside. [Gena Radcliffe]

Tesla

A possibly controversial choice for one of the best films of 2020, Michael Almereyda’s Tesla stretches the definition of “biopic” to punishing lengths. Some of its most memorable imagery, such as Nikolai Tesla (an excellent-as-always Ethan Hawke) toddling around on rollerskates and later singing a mournful cover of Tears for Fears’ “Everybody Wants to Rule the World” look like they came direct from a dream Almereyda had once, then decided to write a whole movie about it. The baffling choice to have Tesla’s story narrated by J.P. Morgan’s daughter Anne, let alone to manufacture a romance when Tesla was famously celibate, may annoy some, but if you go into Tesla understanding that you’re getting maybe 25% of a true story, it’s an affecting, fascinating experience. [Gena Radcliffe]

The Theater on Screen (David Byrne’s American Utopia, What the Constitution Means to Me, Hamilton)

To say that the pandemic has been devastating to the arts would be a vast understatement. A movie at home isn’t a movie in a theater, but it’s still a movie; takeout from your favorite restaurant may not compare to the experience of sharing a meal there, but hey, you still get to eat. Live music, dance, and theater — you just can’t replicate that experience from your living room. Perhaps that adds a level of poignancy to these three remarkable films, but each would be outstanding in any year. Wisely, film directors Marielle Heller, Spike Lee, and Thomas Kail (also Hamilton’s stage director) do not attempt to simply capture What The Constitution Means To Me, American Utopia, and Hamilton as audiences would have experienced them because such a thing is impossible. Instead, each function as a sort of precious record, all the intricacies and subtleties of these remarkable experiences and the performances found therein.

As for those experiences—it turns out those work beautifully in conversation with each other, too. Little need be said about Lin-Manuel Miranda’s juggernaut; Heidi Schreck’s Constitution and David Byrne’s Utopia both conduct their own explorations of the history and future of the United States. None can compare to the live experience, but that’s not the point. The point is to celebrate these performances, these people, and this art form, preserving something ephemeral for the ages. What a gift. [Allison Shoemaker]

Time

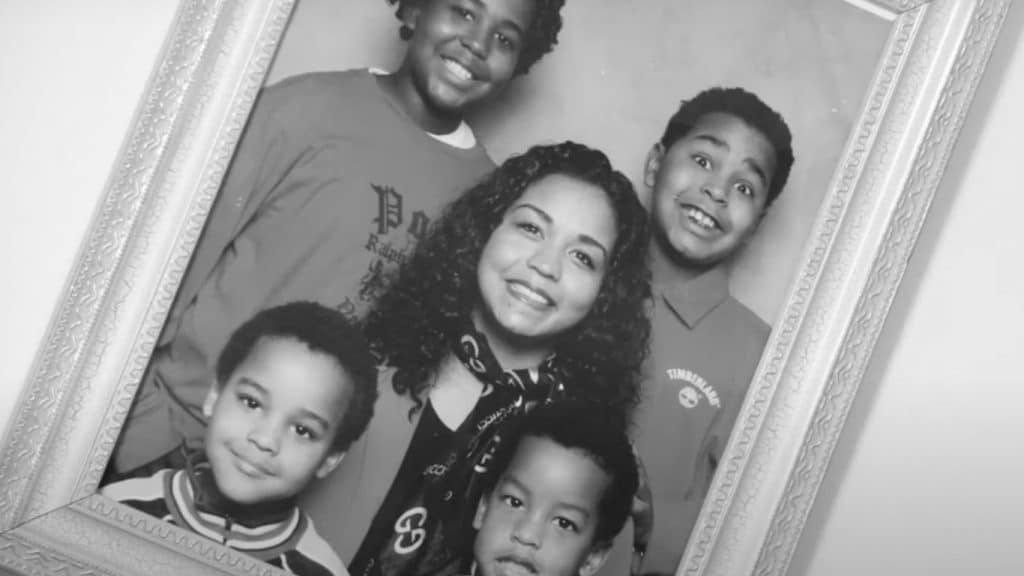

Garrett Bradley’s churning elegy of a documentary, Time, is defined less by what it does than what it doesn’t do. Intent about portraying the conscious passage of hours, days, weeks, months, and years through the perspectives of some of the Rich family, it nevertheless forgoes the procedural approach that would usually characterize non-fiction films about an incarcerated man attempting to regain his life and the effect of that imprisonment on his family. Every moment spent on these efforts leaves a mark and further crystallizes the consuming void of this father and husband’s absence, but the presentation boldly refuses linearity. Time is instead an accumulating slush of past and present — of treated home videos that play as echoes of another life, wounding visual rhymes, and an account of those stuck in rewind when all they want to do is move forward. [Michael Snydel]

Vitalina Varela

Even in objective description, Portuguese filmmaker Pedro Costa’s works defy easy dissection. They’re breathtaking in the density of their compositions, and yet, stubbornly miasmatic in their attention to pregnant stillness and enigmatic but evocative language. They likewise often could be defined as surrealist social realism in their accounts of the people of places like Cape Verde, but that kind of broad distinction feels too firm for something so uncanny. And to further complicate this characterization, Costa is too deeply empathetic as to allow these people to only exist as figures to pose. All of these questions apply to Vitalina Varela, but with a single subject as his focus, the emotional landscape is more narrow and much deeper. And, in turn, Costa dredges the wells of her insurmountable grief as an extended exorcism of an unresolved past. [Michael Snydel]

Wolfwalkers

It’s time to finally bite the bullet and get that Apple TV+ subscription, because Wolfwalkers is a gem. Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart’s beguiling, original Celtic-inspired tale carries within it the wildness, hush, and vivid beauty of a forest, but the real feat is bringing that same quality to the friendship at its center. Wolfwalkers captures the heady highs of a new, fierce friendship, the kind of mutual devotion most commonly found amongst kids on the outskirts, and then finds its reflection in the natural world. Its heartbreaks are undeniable, but its joys even more so. No one wants to start subscribing to yet another streaming service, but this one movie makes it all worthwhile. (Dickinson is also very good.) [Allison Shoemaker]