Sam Raimi and Sharon Stone’s quickdraw revenger is stylish and skillfully crafted.

Every month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema, and the filmmaker’s own biography. October sees not only the onset of Halloween but the birthday of cult horror maestro-turned-mainstream filmmaker Sam Raimi; all month, we’re web-slinging through his vibrant, diverse filmography. Read the rest of our coverage here.

The old west. The Lady (Sharon Stone) rides into the town of Redemption. It’s a town that’s been run ragged by its “mayor,” the vicious-hearted gangster John Herod (Gene Hackman). He lives in a splendid mansion, wears the finest clothes and maintains a skilled band of murderous goons. The exorbitant taxes he levies on his cowed constituents pay for all these luxuries and more. But wasting away in hedonistic excess isn’t John Herod’s style. He’s a nearly fearless man who longs to taste his own fear again. So he’s running (and entering) a quick-draw contest.

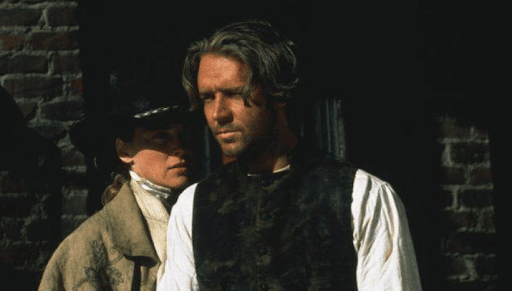

Soon, a whole mess of gunfighters descend upon Redemption. Some, like the loathsome sexual predator Eugene Dred (Kevin Conway) seek to revel in violence and Herod’s offer to foot all their bills for the duration of their stay. Some seek prestige, like the blowhard peacock Ace (Lance Henriksen), the wandering adventurer Cantrell (Keith David) and the local young gun called The Kid (Leonardo DiCaprio). One, the outlaw-turned-priest Cort (Russell Crowe) doesn’t have a choice in the matter. And The Lady? She’s come to Redemption for revenge.

The Quick and the Dead is a blast, even before The Kid’s dynamite stash comes into play. The cast do great work. Director Sam Raimi’s filmmaking winds around the language of the western in interesting ways. The result is a western with a feel all its own.

Stone, who produced in addition to starring, does a really neat riff on the western’s wandering avenger. Skilled and stoic, The Lady aims to end Herod for his crimes. But she’s far from desensitized to death and knowing that Herod needs to die doesn’t make him any less frightening. Stone embodies the laconic cool of Spaghetti Western gunslingers – her entrance is an all-time GREAT Western Hero Introduction – and mixes it with compelling humanity. The Lady’s quest for revenge is a long one. Long, heavy and thrilling.

Hackman crafts a genuine menace in Herod – a worthy, wordy foe for Stone’s often terse hero. He shellacks a thin layer of “class” atop Herod’s bloodthirst and contempt. Yet Herod is not solely a malignant evildoer. He is a man who longs for control, a longing grounded in trauma not unlike The Lady’s – demonstrated best in a great dinnertime monologue from Hackman. And for all his wickedness, he has not wholly snuffed out his own humanity. He’s a bully with power, scary and all too recognizable.

The Quick and the Dead is a blast, even before The Kid’s dynamite stash comes into play.

It’s a treat to see DiCaprio and Crowe playing characters far removed from the roles they’d take later in their careers. DiCaprio’s Kid is a striver, as capable of bubbly sweetness as he is consummate gunslinging. Crowe’s Cort is a good-hearted pseudo-priest fighting to survive despite his certainty that his past crimes have damned him. Both are strong foils to The Lady and Herod.

The remainder of the ensemble are a treat to see, from Henricken’s pompous braggart to David’s cool-eyed professional. They bring life to Redemption, and they’re responsible for a big chunk of the vibrancy that makes The Quick and the Dead work so well.

Credit on that front is also due to Raimi and his collaborators. In particular the work that set decorator Hilton Rosemarin (Hellboy), costume designer Judianna Makovsky (Avengers: Endgame), cinematographer Dante Spinotti (Heat) and editor Pietro Scalia (The Counselor) do is essential to The Quick and the Dead’s success.

Rosemarin’s Redemption is a town that’s being withered away by Herod’s bottomless need for tribute. Almost everything is rundown, a bad day away from toppling over. Herod’s mansion, however, is elegant – even beautiful. It’s an act of architectural vampirism.

Makovsky’s costumes reveal a great deal about their wearers, from how they dress to how they move. The Lady’s trailbeaten leathers are armor to her, in the same way Herod’s fine suits are to him. Cort’s ruined priest’s collar takes even more punishment than he does. Ace’s highly decorated leather ensemble balances precariously on the line between “stylish” and “obnoxious,” until his utter worthlessness punts it far into the latter category.

Spinotti and Scalia craft some stunning vistas and draw upon classic western imagery to great effect. Take, for instance, the use of a spurs-first introductory shot for Herod. It marks him as a dangerous foe who walks around Redemption like he owns it – because he basically does. When that shot repeats with The Lady during The Quick and the Dead’s climax, it’s both a cool moment on its own and a visual representation of The Lady pulling one over on Herod and reversing their power dynamic.

Raimi’s filmmaking is zippy and creative. His experience with horror comes to the fore in shots of Redemption where the town, at its emptiest, seems downright eerie. His experience in comedy lends itself well to The Lady’s frustration with The Kid’s flirting and occasional moments of odd visual humor. When The Lady first arrives in town, a lone spyglass observes her from one of Herod’s windows. It’s a distinctly “Sam Raimi” moment, one of many in The Quick and the Dead.

Raimi’s experience with action makes for thrilling battles, whether shown in full or in montage. The Lady and Herod’s final showdown is climactic, cathartic and thrilling – even if it is on paper quieter than the massive explosions which precede it.

The Quick and the Dead is an excellent modern western, a darn good film generally and a testament to Raimi’s flexibility and skill as a filmmaker. Seek it out.