Two of our writers discuss how a perhaps unhealthy fear of God makes William Friedkin’s most successful film so effective.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

The funny thing about William Friedkin is that if you ask six people what their favorite Friedkin film is, you’ll get six different answers. These hot and cold responses marked Friedkin’s career overall, one that, for all its faults and stumbles, was never predictable or boring. He had no trademark and refused to be pinned down.

This piece was written during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike. Without the labor of the actors currently on strike, the works being covered here wouldn’t exist.

Welcome back to Filmmaker of the Month. In honor of the film, and in its spirit, we sent in a young writer, Megan Sunday, and another young writer, Gena Radcliffe, to do spiritual battle with The Exorcist.

GENA: Thanks to my mother’s questionable judgment, I first saw The Exorcist when I was maybe 9 or 10. This was in the early 80s, when a heavily edited version of it ran on network television, and before William Friedkin began tinkering with it, evidently unhappy with the original despite the fact that it was up to that point one of the most financially and critically successful horror movies of all time. “You can’t mess with perfection,” one could say, to which Friedkin would have responded, “Watch me, asshole.”

Typical of my experience watching scary movies as a child (and I watched way too many), I was both horrified and fascinated by it. I suppose I knew what The Exorcist was as a concept, but to actually see it, let alone discover that it was even scarier than what I had been led to believe, was a pivotal moment, both as a horror fan, and as someone who even as a child had a complicated relationship with God and religion.

MEGAN: In my house, The Exorcist was held up as a monolith. The only horror movie that ever scared my dad, origin of the spookiest track on Pure Moods, The Exorcist seemed more forbidden than even the slasher movies my mother outlawed. That was my mom’s rule; not seeing a movie about demons seemed like God’s. Oh, I knew bits and pieces, everyone did. I knew about the head-spinning and the pea soup and saying the word “cocks” to a priest. All that pop culture ancestral memory aside, the very idea of a little girl being possessed by a demon seemed like the absolute worst story for a movie, since, after all, it was something completely possible. Freddy and Jason, though scary, were fiction, impossible; the Devil? Now that was real.

GENA: I had forgotten until you mentioned it there that Mike Oldfield’s “Tubular Bells” was a featured track on Pure Moods, a collection of new-age instrumentals meant to be played in a massage therapist’s waiting room. As opposed to, say, Enya or Deep Forest, there’s nothing soothing about “Tubular Bells.” Like John Carpenter’s equally iconic theme for Halloween, it’s chilly and discordant, creating an immediate sense of unease. You play that in a crystal shop, you’re clearing it out in 30 seconds flat.

And yes, the sense of oh shit, this feels too real is what makes The Exorcist, even (unbelievably) fifty years later, so effective. Virtually all Christian religions teach some concept of “the Devil,” but that’s it, it’s a concept, a vague idea of some sort of malevolent force that’s responsible for all the sorrow and suffering in the world. Nobody knew exactly what it looked like, or how it would present itself to the unassuming virtuous. The Exorcist, however, made it abundantly clear: the Devil was a defiler of innocent flesh, whose sole purpose was shattering our faith in God, often by tormenting us with our own weaknesses.

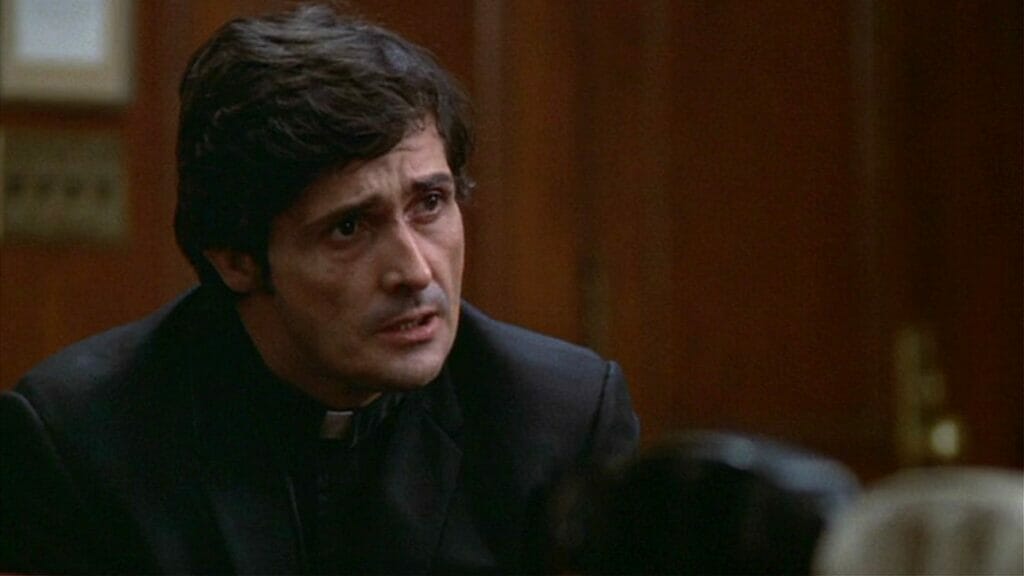

MEGAN: When I finally saw The Exorcist, it both confirmed and baffled all of my expectations. It was a terrifying journey into a miasma of religion and guilt and pain, complete with flashes of a demonic face that I still cannot handle seeing unprepared; but it was also a moving look at the challenges of faith and parenthood. Father Damien Karras (Jason Miller) believes in God almost as a technicality (he’s a priest, after all), but his mind is occupied with his work as a psychiatrist and the weighing care of his infirm mother. Chris MacNeil (Ellen Burstyn) is a working actress, social butterfly, and single mother who has probably never thought any longer about demons than she has a particularly fat pigeon on the sidewalk.

These adults, so burdened as they are by the ordinary challenges of daily life, somehow find themselves the perfect victims for a particularly nasty piece of demonic work named Pazuzu, who possesses Chris’ daughter Regan (Linda Blair) after she messes about with a Ouija board, demonstrating very clearly to little Catholic me that those tricky board games were evil after all.

The Exorcist isn’t just frightening at a visceral level, it’s bleak on an existential level.

GENA: If we had more time here I’d segue into a story from my adolescence about the time I messed around with a Ouija board and became convinced that I had summoned a demon. Point being, it was specifically because of The Exorcist that I knew that playing with a Ouija board was like playing a game of Ding-Dong-Ditch with the door leading to Hell. But Regan doesn’t know that. Here, the demon that possesses Regan is so insidious that it comes to her as a friend, preying on her loneliness. With a mother who loves her but is constantly working, and a father who forgets to call her on her birthday, she’s ripe for a kind voice. It’s not unlike the way a sexual predator hones in on a child who’s playing by themselves at the park, and it’s chilling.

Though more attention went to the subliminal imagery and the restored “spider walk” scene, 2000’s “Version You Haven’t Seen” included a previously deleted conversation between Father Karras and veteran exorcist Father Merrin (Max Von Sydow) about why the Devil has chosen a blameless child to terrorize. “I think the point is to make us despair,” Merrin, who looks like he’s spent his entire life despairing, explains. “To see ourselves as animal and ugly. To make us reject the possibility that God could love us.” What an idea to put forth to Catholics, who are raised from birth to believe that the only thing saving us from eternal damnation is God’s love! How do we sleep at night knowing He might not love us, and thus nothing will save us? I’ll take a masked killer over that thought any day.

MEGAN: Perhaps the most and least surprising thing about The Exorcist’s longevity has been the entry of its most terrifying aspects into the watered-down cuteness of popular culture. As we write this, you can buy a plush possessed Regan doll just in time for Halloween. The famed stairs (in reality wedged near a gas station) are the frequent backdrop for dramatic Instagram reenactments of Karras’ deadly fall. Even I, stricken though I still am by the movie’s images, own an Exorcist coffee mug (it does not feature Pazuzu, however). It must, however, be noted that an influx of merch has done little to dull the film’s scares. You can prepare yourself to see someone’s head spin around, but there’s no preparation for worrying if God is really looking out for us.

GENA: Yes, true, in The Exorcist God does “win,” inasmuch as the Devil is eventually driven out of young Regan, though both Merrin and Karras die in the process. I suppose you could look at it as mercy: even before confronting the literal face of evil Karras was distraught, both over his crisis of faith and the death of his mother. Perhaps such an act of sacrifice brought his soul peace. We can only hope, though in The Exorcist III, written and directed by William Peter Blatty, Karras’s suffering continues, with his body being used as a conduit for the soul of a serial killer.

Even without that particularly cruel twist, The Exorcist itself ends on a disquieting note. Regan doesn’t remember anything that’s happened, but everybody else does. Chris, her mother, looks shell-shocked, as though she’ll never sleep without the assistance of heavy medication again. The once boisterous, wisecracking Father Dyer, forced to give last rites over the broken body of his friend, is now subdued. Evil has left its mark on them all, and it knows their secrets.

MEGAN: The most memorable scene in the film isn’t even really any of Regan/Pazuzu’s antics: it’s Father Karras’ dream of his mother, moving as though through a thick body of water, calling out desperately for someone just out of reach. That poignancy beats disgust any day. Karras’ mother, Regan’s soul, God Himself: they spend the movie beyond their loved ones’ ability to reach.

GENA: The Exorcist isn’t just frightening at a visceral level, it’s bleak on an existential level. Father Karras is a fundamentally decent man, wracked with guilt over his very human doubts and inability to serve both his religious calling and his familial responsibilities at the same time. Is God punishing him for something, or is it that he’s simply so inconsequential a person that he doesn’t even register on the great radar screen of life? These thoughts have literally kept me up at night, and the older I get (which means the more I face my own mortality), the more I wonder: What if none of this matters? What if we’re all just lost?