Though mostly a by-the-numbers courtroom drama, this little seen thriller poses some uncomfortable questions.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

The funny thing about William Friedkin is that if you ask six people what their favorite Friedkin film is, you’ll get six different answers. These hot and cold responses marked Friedkin’s career overall, one that, for all its faults and stumbles, was never predictable or boring. He had no trademark and refused to be pinned down.

This piece was written during the 2023 SAG-AFTRA strike. Without the labor of the actors currently on strike, the works being covered here wouldn’t exist.

Even before the internet, certain movies had reputations they didn’t quite live up to. Some, like Salo or 120 Days of Sodom, earn their mythical status as movies designed to make your skin crawl and your stomach clench. Others, like the Faces of Death series, while unpleasant to watch, were just empty, acting as a controversy delivery devices and nothing more. Others still, like William Friedkin’s Rampage, never courted outrage. But unlike those others, whatever reputation it earned before the public got a chance to see it didn’t much help. As a result, at least partially, it remains one of the more obscure releases in Friedkin’s filmography.

While filmed in 1987, Miramax didn’t release Rampage in the U.S.–save for one screening in Boston–until 1992. Despite being in a career slump at the time, it was still puzzling to see a film written and directed by Friedkin so unceremoniously buried. Speculation had it that the movie was too horrifically violent to release. Friedkin making several changes while Rampage sat on the shelves, including giving it a completely different ending, only made the “it’s too horrible for polite society” theory more plausible.

As it turned out, the truth was far more boring. The production studio, Dino DeLaurentiis’s DEG, went bankrupt before releasing Rampage. Picked up by Miramax (presumably for $10 and some McDonald’s gift certificates), it barely saw the inside of a movie theater before curtly dumped onto home video. Even years later, it’s only gotten a DVD release in Poland and is currently only available for rent on Amazon. That’s a shame. It’s a fairly standard crime procedural and isn’t much more gruesome than, say, Manhunter, which it somewhat resembles stylistically. However, Rampage is interesting as a platform for Friedkin to try working out his complicated feelings about the death penalty

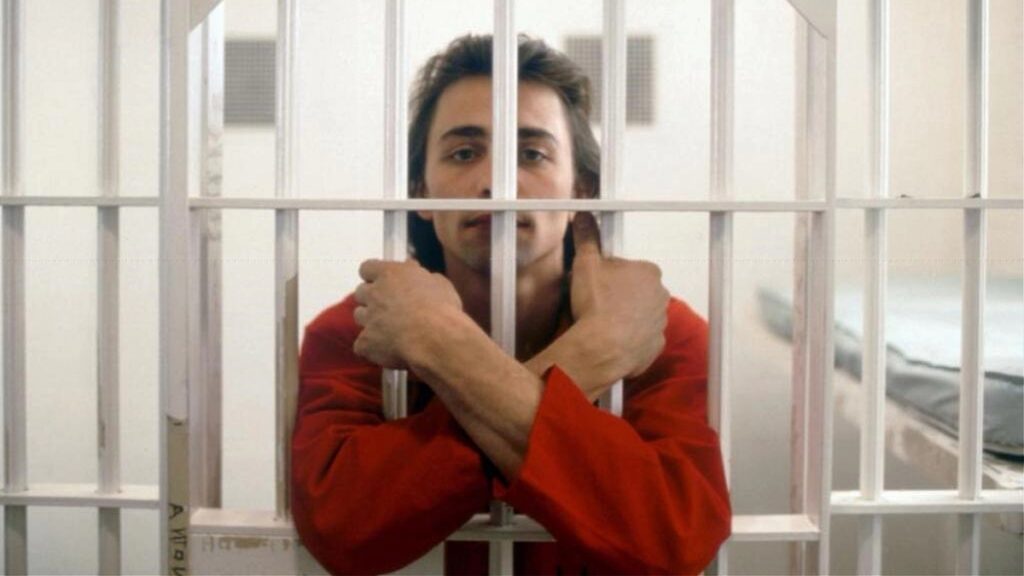

Based on William P. Wood’s lurid novel of the same name and loosely inspired by the real-life case of “Vampire Killer” Richard Chase who terrorized Sacramento in the late 70s, Rampage centers Chase’s fictitious counterpart, Charles Reece (Alex McArthur, best known to Gen Xers as Madonna’s dreamy boyfriend in the video for “Papa Don’t Preach”). He’s arrested, but not before murdering and mutilating two families (including a child), taking their internal organs, and drinking their blood. Assistant District Attorney Tony Fraser (Michael Biehn), already worn down by the recent death of his young daughter and the other horrifying cases in his workload catches the case. Not only is he to prosecute Reece, but he’s to seek the death penalty. Given the nightmarish circumstances of the case, it should be an easy “win” for Fraser. The only obstacle is Reece’s public defender (Nicholas Campbell) pushing an insanity defense.

Here lies the conflict at the center of Rampage. Reece’s crimes, not to mention his basement full of body parts (and Nazi flags and pornography, this is not a particularly subtle movie), are clearly the work of a diseased mind. No average person in control of their faculties could inflict such horrors upon other human beings. It would seem both unproductive and cruel to kill someone for acting in a way they can’t control. But also, quite simply, what do you do with a diseased animal? Whose responsibility is it to keep him away from society? And what happens when it’s time to let him go?

[A]n interesting movie that poses some uneasy questions without easy answers.

Rampage was released at a curious time in American pop culture when film and television had a very conservative agenda. Crime films, in particular, encouraged distrust of the justice system, but not because of the reality of police and prosecutorial misconduct. Instead, it was the misconception that all a criminal had to do was claim mental illness and essentially go unpunished for their crimes. Sylvester Stallone’s Cobra and Charles Bronson’s 10 to Midnight both end with their serial killer villains smugly proclaiming a judge will find them too “sick” to go to jail. That’ll leave them free to kill again, forcing the heroes to kill them first. In real life, less than 1% of court cases involve insanity pleas, and only a quarter of those are successful. It is not an easy way for a defendant to get out of paying his debt to society.

That’s not exactly the claim Rampage is trying to make. Oh, it definitely has some unflattering things to say about the psychiatry industry, as illustrated by Dr. Keddie (John Harkins). He encourages another psychiatrist to lie about Reece’s previous hospitalization so they can study him “for the betterment of society”. He’s a real Ash from Alien. On the other hand, testifying for the prosecution is a psychiatrist whose opinions are so uniformly hard-line against defendants that his nickname is “Dr. Death”. There are no gray areas here when it comes to psychiatry. Both Wood’s novel and Friedkin’s script paint all psychiatrists as dishonest, opportunistic weasels.

On the subject of the insanity defense and the death penalty, however, the film offers a nuanced and challenging perspective. Initially, the movie heavily implies Reece is faking his mental illness, as evidenced by his ability to remain calm when the situation calls for it and his knowing smirk when asked if he hears voices. Nonetheless, during the trial’s penalty phase, it’s revealed he is, in fact, schizophrenic. This diagnosis spares him from the death penalty, instead sentencing him to a psychiatric hospital. There it’s possible, however remotely, that he might get out someday, still sick, still a danger to society. It is legally (and, to many, morally) the right thing to do for Charles Reece, but what about everyone else?

Rampage isn’t a hidden gem of Friedkin’s filmography. There are too many lapses into melodrama. Biehn and McArthur lack the charisma to play the hero and villain effectively. Ennio Morricone’s intrusive score seeps into every scene like he was paid by the note. But it’s an interesting movie that poses some uneasy questions without easy answers. Friedkin also tries a few creative spins on the courtroom drama genre. For example, Tony, during his closing argument, asks the entire courtroom to sit in silence for three minutes, the amount of time it took for one of Reece’s victims to die. It’s an impactful moment. Many real-life lawyers would have probably used it to good effect in their own cases, if ever given a chance to see it.

The film also suggests a parallel between Reece’s miserable childhood with an abusive father and smothering mother (Grace Zabriskie, playing “crazy mom” as only she can) and the loving relationship between the husband and pre-school age son of one of his victims. Despite his grief, the father still manages to create a safe and loving place for his child. Maybe if Charlie had that kind of love and safety in his traumatized life, things would have turned out differently. Or maybe nothing would have changed at all. There’s just no way of knowing.