Wheatley’s first encounter with a movie star, Tom Hiddleston, dives deep into humanity’s social climbing dark side.

Every month, The Spool chooses to highlight a filmmaker whose works have made a distinct mark on the cinematic landscape.

With his love of mixing horror, dark comedy, and crime Ben Wheatley has been flirting with but never breaking through to the mainstream. However, this month that may all change.

This piece was written during the 2023 WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes. Without the labor of the writers and actors currently on strike, the movies being covered here wouldn’t exist.

The first night I moved into my apartment, the couple upstairs having particularly loud sex kept me awake. The mixture of their moans and the dull thud of what I assume was the headboard against the wall went on for nearly ten minutes, increasing in speed, before I dragged myself out of bed to search through the yet-to-be-unpacked boxes piled up in my living room for some earplugs. Two days later, I saw the couple in the stairwell. They were none the wiser that I had overheard their intimate, private encounter.

Living communally, that is, within estates, apartment blocks, or high-rises, offers a specific type of intimacy. It is one that potentially opens up the private aspects of your life to your neighbors. Banalities such as when you go to sleep and wake up, what genre of music you listen to, whether you sing in the shower, and how often you order in and from where are shared with those living around you.

It’s not just these seemingly unimportant details. Residents share more revealing aspects of their lives as well. Relationship status, partner arguments, and, like the couple above me, sexual encounters may all stand exposed. In these closed spaces, where existences are separated only by thin walls, there is a sense of knowing and not knowing. That condition gives them a sort of limbo quality. You might know your upstairs neighbors bicker over money without ever knowing their names.

I was thinking about all this when I first read J.G. Ballard’s 1975 novel High-Rise, a near-future novel set in a tower block on the outskirts of London. Designed to be a modern haven for the contemporary city-dweller, the high-rise soon becomes a chaotic zoo of violent and aggressive behavior. The plot may have once felt far-fetched, but after living in my apartment for a few months, it quickly came to feel like a recognizable possible reality.

Whenever my blood boiled about where the penthouse owners had parked their sports cars, or I felt unbridled rage at a bureaucratic email sent by the building’s manager about acceptable behavior–no drugs, no loud music, no ballgames, no doormats!)–I had visions of acting out my secret fantasies. Dragging a key along the bodies of those ugly sports cars. Smashing their windows with a golf club. Throwing wild parties with thumping music on a boombox until five in the morning.

I have not, as yet, given in to these desires. However, the characters in Ballard’s novel, and its 2015 film adaptation by Ben Wheatley, do. It begins with a series of power failures. Rather than share some diminished ration of energy, the remaining power is rerouted to the upper floors so the wealthier inhabitants can carry on with their parties. Soon, those on the lower floors revolt. Dogs are slain, people murdered, and sexual violence perpetrated. The entire building devolves into an unruly, lawless place. Nonetheless, it is one that remains recognizable. As Ballard puts it in the novel, “In a sense, life in the high-rise had begun to resemble the world outside—there were the same ruthlessness and aggression concealed within a set of polite conventions.”

In this way, Wheatley’s film retains Ballard’s politics. It is a violent and bloody tale of class warfare. One that spirals increasingly toward chaos, reflecting the world around us. In its committed surrealism, the high-rise inhabitants go to battle each night. They watch bodies fly from the higher floors and crash into the cars below. And yet, they still go to work each morning. Just as we, in our daily lives, watch abject terrors on the news before heading into the office, the façade of their lives must go on.

The rage and violence of the high-rise is just another contemporary horror they have to deal with. Wheatley is not subtle in his approach to these ideas, but neither was Ballard. As the novelist Zadie Smith noted, “In Ballard, the dystopia is not hidden under anything. Nor is it (as with so many fictional dystopias) a vision of the future. It is not the subtext. It is the text.”

Wheatley’s film is much the same. High-Rise juxtaposes the wild, clean, and curated world of the upper floors with the darker and dingier lower ones. The film, perhaps, is at its best when capturing these liminal, sometimes called “Ballardian,” spaces. The production design that brings Ballard’s high-rise to life is bleak and brutalist. It is reminiscent of the famous Barbican estate in London, under construction when Ballard wrote the novel.

To this end, Wheatley retains the novel’s time period. This choice keeps the action set within the seventies rather than updating it to reflect contemporary Britain, where high-rises are far more common but tarred with different issues concerning class and safety. When Ballard wrote the novel, living in high-rises was still relatively new. Ballard’s native England saw their first tower blocks built in 1951. Back then, advertising sold “living high” to the consumer as a purer way of life. The light was brighter, the air was cleaner, and the structure was modern. People, however, didn’t buy it. Instead, to most, the high-rise symbolized overpopulation by presenting a need to build upward to accommodate.

The film, perhaps, is at its best when capturing these liminal, sometimes called “Ballardian,” spaces.

High-rises, inspired by modernism and a break from traditional architecture spurred on by technological advancements, interested Ballard. To him, they were eerie liminal spaces with a clear and distinct visual hierarchy that mirrored England itself. Those with the most money lived on higher floors. Those with less literally had to live below them.

Additionally, they offered a new way of being, one untethered from the past. In older buildings, one knew how to act given the space–and its rules–were long established. High-rises, on the other hand, were new and, theoretically, offered new ways to behave. Not only did they foster that sense of strange, almost intimacy between neighbors, but they often became spaces that provided few reasons to leave. Both the film’s high-rise and the Barbican estate offer many on-site amenities, from shops to swimming pools, gardens to art galleries.

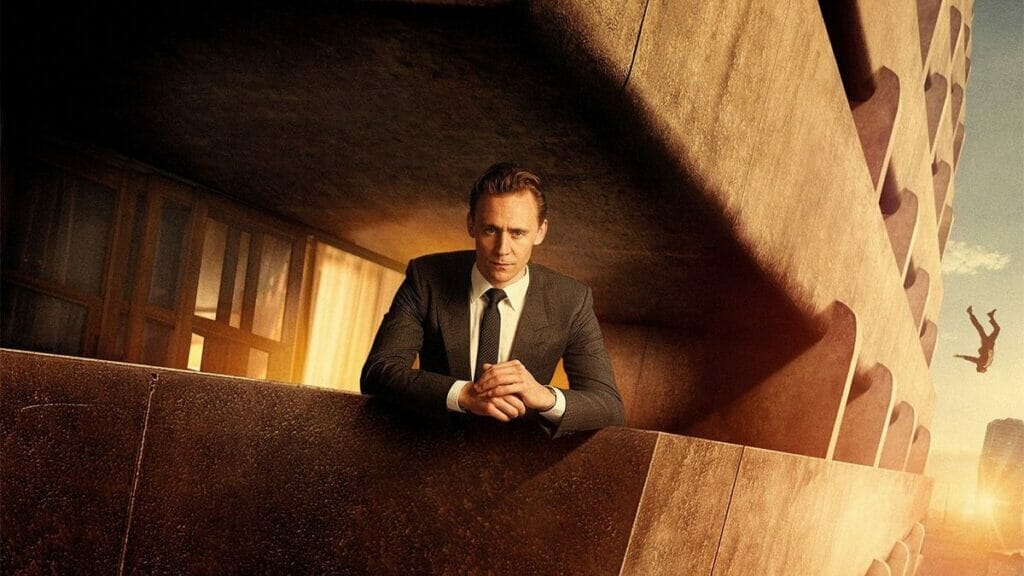

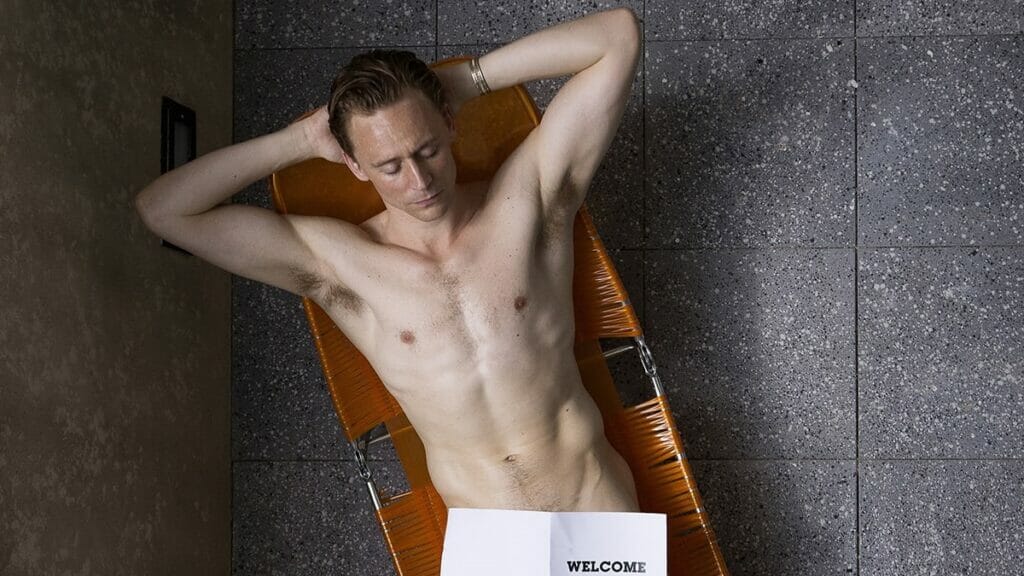

Yet, these spaces are not available to all. Only a few with the “right” amount of social capital have access. What floor are you on? How much money do you have? It’s these kinds of spaces Dr. Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston) finds slowly opening to him. This vertical movement from his concrete-walled, poorly lit apartment to the sunlight-bathed private gardens of the building’s architect, Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons), allows Laing to get a taste of what life above might be like.

As a medical school lecturer, Laing sits at the cusp. He is neither one of the building’s top inhabitants nor one of its lowest. He dwells firmly in the middle class. His apartment, located toward the middle of the high-rise, affords him a certain glimmer of social mobility. The upper floors don’t detest him in the same way they do the often vulgar Richard Wilder (Luke Evans), a shaggy documentary filmmaker with 70s sideburns and scruffy facial hair. Still, those in the upper echelons don’t totally embrace Laing, either. The rich frequently mock him when he’s in their company. They snigger over their champagne as if his aspirations for a better life, one that might look something like theirs, can be sniffed out a mile away.

Evans’ committed and daring performance sells [the madness] to us.

Unfortunately, when attending the parties on the floors below, he also meets a skeptical eye. His interactions with the upper floors give him an air of haughtiness, a suggestion he might think he’s better than everyone else. The sleek, tailored suits that costume designer Odile Dicks-Mireaux dresses Hiddleston in mirror this. As the high-rise begins to decline into chaos, Laing never takes off his suit, not even when splashed with paint or blood. It signals his commitment to social mobility, to living higher, is perhaps his strongest desire, one more powerful than even his need to survive.

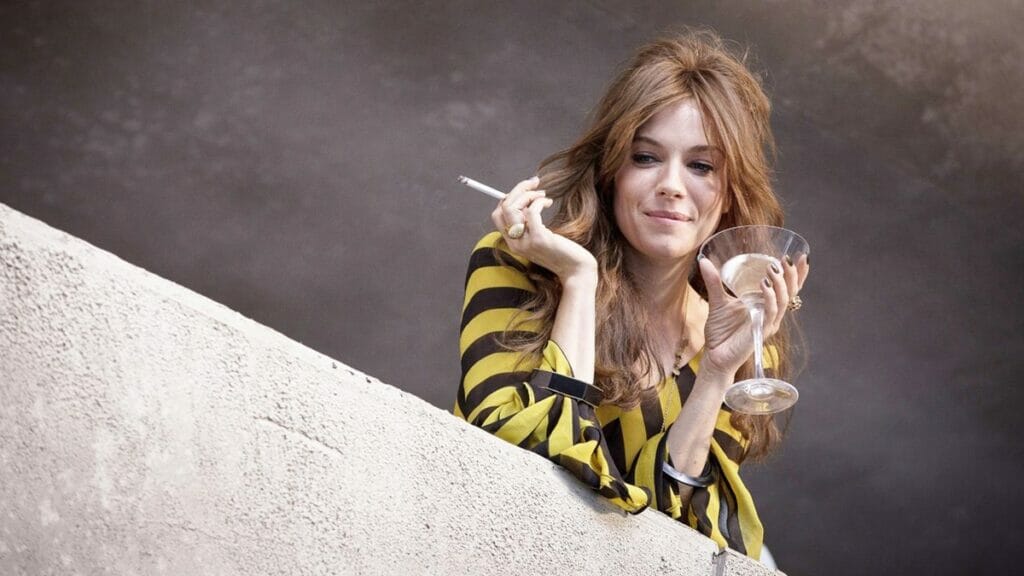

If Laing, then, does his best to retain all composure in the wake of the violence, his opposite is Wilder. The documentarian quite quickly devolves into a hulking mass of animalistic aggression. Even before the chaos begins, Wilder attempts to push himself out of his social trappings by continually seeking the affections of Charlotte Melville (Sienna Miller), a glamourous single mother who lives on the floor above Laing. Despite being married with children, his desire for Charlotte is palpable. Meanwhile, she never returns his advances, taking more interest in the silky, socially mobile Laing.

Charlotte herself is of little concern to Wheatley or Ballard. It is safe to say that in the film, as in the novel, the women have little to do, acting more as pawns in the power games between Laing, Wilder, and Royal. It proves especially noticeable onscreen where the likes of Miller, Elizabeth Moss, and Keeley Hawes, three actresses who have proven more than capable of shining on the screen, are cast in these thankless roles.

Unlike Laing, it seems Wilder has nearly no chance of rising beyond his station. As such, his attempts prove to be a Sisyphean act of will. It is no wonder then that, once the chaos ensues, Wilder embraces it wholeheartedly, deliberately provoking the upper floors at every turn. If they won’t invite Wilder to the parties, he will make his presence known by force. In one scene, Wilder gathers a gang of excitable and screaming children and leads them straight to the pool, disrupting a party for the rich. He watches the upper classes squirm while children jump in and splash around.

Wilder’s willingness to be violent, and his resentment at the rejection he feels, make him a dangerous and ruthless enemy. Toward the film’s end, Wilder becomes unhinged and frightening, wrapped in shreds of blood-spattered clothes. While we never quite get the completely nude, phallus-obsessed, wolf-like Wilder of the novel, Wheatley, perhaps, pushes it as far as the BBFC would allow. Wilder’s desire for a life outside of his class drives him mad. Evans’ committed and daring performance sells all of this to us.

As is inevitable, the film reaches a violent end. The chaos of the high-rise marches on and becomes the new normal. Laing, recreating the novel’s famous opening line, sits on his balcony, eating an Alsatian that he has caught and roasted over a fire. He is still in his shirt and tie. When cast amongst the abject nature of these actions, his sense of decorum emphasizes a kind of madness that can only come from living under such conditions. In the end, Wilder says it best: “Living in a high rise requires a special type of behavior. Acquiescent. Restrained. It helps if you’re slightly mad.”