Every month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema and the filmmaker’s own biography. For July, we honor the chameleonic genre-bending of the recently-passed Joel Schumacher, who embraced camp thrills and pulp trash in equal measure. Read the rest of our coverage here.

Life does not go as planned. This may seem like a cruel understatement in the cursed year that is 2020, but the old maxim about the best laid plans of mice and men has always been true. You start your life with one set of goals and then wake up one morning wondering how you ever got so far off course. You think that the world operates in a way that leans towards justice only to be smacked across the face with the cruel realization that evil lurks behind even the most banal corners.

Once that bubble has burst, is there any going back? If you’re confronted with sheer darkness, does it make you complicit to ignore it? Now that you put nipples on the bat suit and everyone hates you for it, what’s your next move? Well, if you’re Joel Schumacher, you make one of the most upsetting, disturbing, and outright gross films ever released by a major studio, 1999’s 8mm. If you thought the caped crusader’s costumes looked like fetish gear, just wait until you meet Machine.

Tom Welles (Nicolas Cage) is a mild-mannered private investigator. He lives a quiet life with his wife, Amy (Catherine Keener), and their newborn daughter. They’re happy enough, but Tom is constantly chasing a big case, one that will leave them financially sound forever. When Daniel Longdale (Anthony Heald)—attorney for one Mrs. Christian (Myra Carter) who’s recently widowed from her industrialist millionaire husband—contacts him, Tom thinks his luck may be turning around. Then he receives his assignment: amongst her late husband’s possessions, Mrs. Christian found what appears to be a snuff film. She wants Tom to investigate and find out if the young woman in the film was actually murdered, or if it was all just an elaborate hoax.

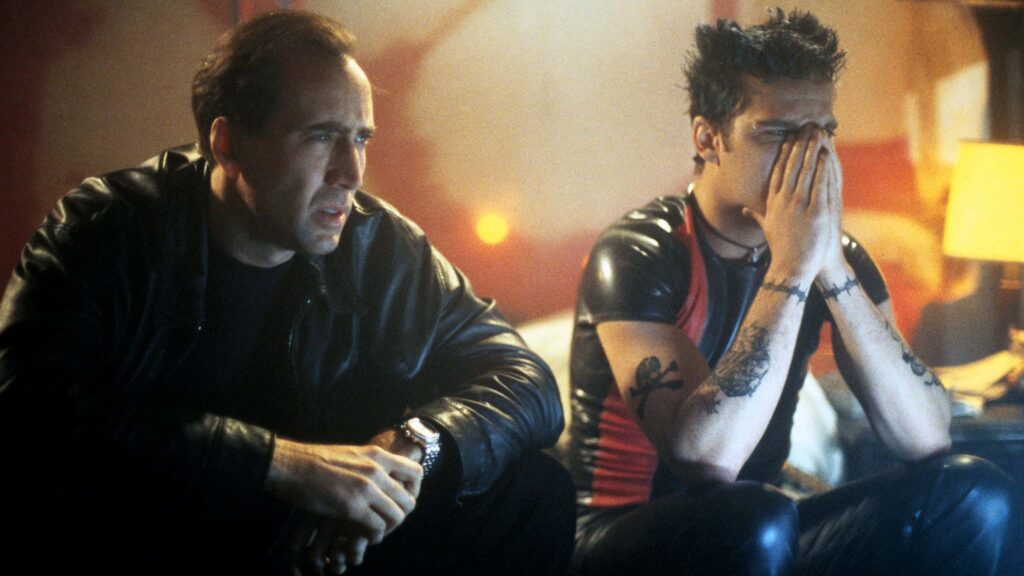

Tom’s quest for the truth leads him down into the dark underworld of illegal fetish pornography. His tour guide on this River Styx of smut is Max California (Joaquin Phoenix), a XXX video store clerk who introduces Tom to all sorts of seedy characters. These include Eddie Poole (James Gandolfini), a goateed pile of flop sweat who runs Hollywood’s grodiest casting couch, and Dino Velvet (Peter Stormare), a foppish goth who directs torture porn, but not of the Saw variety.

And then there’s Machine (Chris Bauer). Machine is the DeNiro to Velvet’s Scorsese, a permanently masked, permanently mute, stone cold psychopath who does unthinkably horrific things to women when the camera is rolling and enjoys every minute of it. If there was ever a character perfectly designed to get your skin crawling and make you want to take a long shower, it is Machine.

As you can see, Schumacher assembled quite a cast here. Bauer accomplishes so much with so little, imbuing even Machine’s smallest hand gestures with chilling menace. Phoenix, sporting blue hair and leather pants, radiates a mixture of boyish charm and world-weary cynicism that only he could pull off. It’s always a pleasure to see the late great Gandolfini these days and to remember how thoroughly he excelled at playing amoral two-bit street rats before he became known as Tony Soprano. (It’s impossible not to grin at the kismet when he sneeringly calls Cage’s character a “big pussy.”)

However, for my money, it’s Stormare who steals the show. Fully embodying “the Jim Jarmusch of S&M,” as Max calls the character, Stormare clearly understands the kind of film he’s in. He responds by devouring the scenery, swinging around a crossbow, and piling on vocal tics and weird mannerisms with such verve and abandon that you can’t help but laugh at how few fucks he gives.

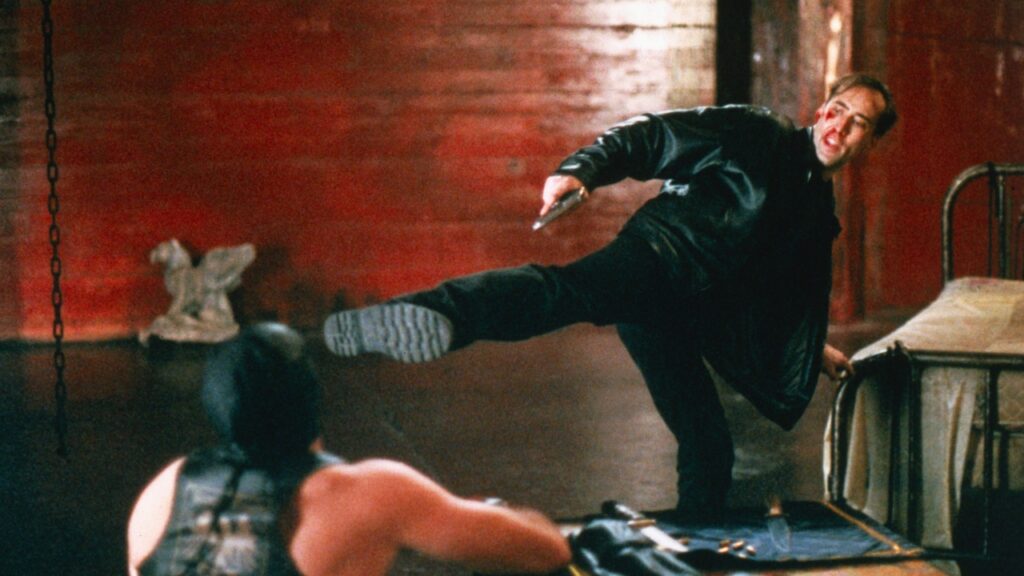

Speaking of scenery chewing, let’s talk about Cage, the California Klaus Kinski himself. These days it’s nigh impossible to imagine that there was once a time when Hollywood would cast Cage as the relatable audience surrogate—but there was such a time, and it’s called the ‘90s. For how over-the-top and lurid 8mm often gets, Cage’s performance is surprisingly measured and quiet. The few times that he goes into full on straight-to-video “Rage Cage” mode feel incongruous and out of place. He’s hindered by a lot of technical police-speak dialogue, especially towards the beginning of the film, but he mostly succeeds when it really matter—that is, selling Tom’s journey from passive observer to vengeful crusader.

Would we rise to the occasion when confronted with pure evil? Can we bring ourselves to kill if it’s just not in our nature? Instead of just having Tom go on a rampage and rack up a body count like most films would, 8mm really makes the audience sit in these questions. While most of us think that we could take an eye for an eye if need be, the truth is probably much closer to what happens to Tom. Given the chance to avenge the death of the girl he’s been searching for, he freezes. Not only does he freeze, he goes so far as to call the girl’s grieving mother (Amy Morton) and ask her permission to take a life in her daughter’s name. 8mm may not be the smartest of films, but you would certainly never see Charles Bronson weighed down by such a moral quandary.

Would we rise to the occasion when confronted with pure evil? Can we bring ourselves to kill if it’s just not in our nature? Instead of just having Tom go on a rampage and rack up a body count like most films would, 8mm really makes the audience sit in these questions.

Indeed, if there’s one thing that dates 8mm quite painfully is its need to constantly remind you that this ain’t your daddy’s detective story. It may be unfair to compare the film to Se7en, but it’s impossible to avoid. Andrew Kevin Walker wrote both films, and 8mm often seems like an attempt at stretching his previous film’s lurid sex dungeon sequence out to feature film length. Both films have that jaundiced, grainy, Nine Inch Nails music video aesthetic courtesy of Paul Thomas Anderson’s former go-to DP, Robert Elswit.

All the walls in this movie look like they’re painted black and covered in goo, and even the L.A. sun looks diseased. Both films feature jaded law enforcement types touching the void and being rather taken off guard when the void touches them back. The one major difference, of course, is that you’d be hard pressed to confuse David Fincher with Schumacher.

As far as directors go, Schumacher is a technician. He played around in far too many genres and cross-pollinated too many visual styles to ever be considered an auteur, not to mention critics often afforded him zero respect. This is not an insult: if Schumacher was brought in to replicate Fincher’s style (minus the perfectionism that gave studios headaches), he more often than not rises to the occasion. He was already well versed in louche urban darkness thanks to The Lost Boys, Flatliners, and Falling Down, though the graffiti-strewn alleys here dredge up some memories of his Batman films’ neon biker gangs. He’s more than happy to join Walker in perverting normality; at least one character here ends up crucified.

Schumacher even pulls off one all-time bravura suspense sequence in Tom’s final confrontation with Machine. Shot in intimate, hand-held documentary style as our hero tracks the murderous gimp through a creepy old house, it is as thrilling as it is unnerving. You know what sounds scarier than “Come to Daddy” by Aphex Twin? How about “Come to Daddy” by Aphex Twin being ripped off the turntable, just the scratch of the needle mocking your restless heartbeat?

Still, despite a long and storied Hollywood career full of both major blockbusters and even the occasional critical hit, it’s hard to not feel a bit sorry for Schumacher. In a rollicking and often very fun interview with Vulture published less than a year before his death this past June, Schumacher reflects on the pain of knowing that you’re not destined to be one of the greats: “It’s very hard to realize that you have a calling and realize you’re not gifted. I wanted to be a director all my life, and when I finally got the chance, I was so miserably untalented.”

It’s not hard to see why Schumacher could relate to the characters of 8mm: Tom studied law at Penn State but went for a less lucrative career in surveillance, a decision that clearly haunts him. Max went out west with his punk band looking for a record deal, but the band imploded upon arrival, and now he finds himself selling pocket pussies to Sunset Strip scum.

Then there are the much darker ways in which 8mm may have spoken to Schumacher: in that same interview, the director speaks very candidly about his wild and dangerous childhood. Schumacher’s father died when he was four, and his mother worked full time, leaving the young boy more or less unattended and with appetite to explore life’s many vices. As Schumacher himself puts it, “I started drinking at 9, smoking at 10, and fooling around sexually when I was 11.” Elsewhere in the article, Schumacher, who was openly gay, references various relationships with much older men when he was still a teenager, though he goes to pains to explain that he never felt that he was abused.

Regardless, it’s hard to hear about this man with a childhood so thoroughly robbed of innocence and then watch his film about a man fighting in innocence’s name. Unfortunately, life is not that black-and-white, and eventually all that Tom Welles and Schumacher are left with is the sound of the projector. It whirs nonstop until they can stir themselves to turn it off and head into the sunlight once more.