Paul Schrader’s kinky erotic thriller offered both style & substance, and still holds up.

These days, when confronted with a film made in the past featuring material that comes across as somewhat outre by contemporary standards, it’s practically to remark that there’s no way such a thing could be made in these comparatively staid times. In the case of Paul Schrader’s Cat People (1982), one comes away from it not only thinking that it couldn’t be made today, but wondering how in the hell it was able to get made back when it did. Bloody, erotic and suffused with a level of kink rarely seen in a putatively mainstream project, this go-for-baroque spectacle was an outlier when it first came out 40 years ago and that feeling remains undiminished to this day, along with its ability to simultaneously raise eyebrows and libidos at every turn.

The film was a remake of the 1942 film from director Jacques Tourneur and producer Val Lewton that part of a series of low-budget projects. Written by DeWitt Bodeen, it began with Serbian fashion designer Irena Dubrovna (Simone Simon) and American engineer Oliver Reed (Kent Smith) meeting and falling in love. Irena confesses that she is the descendant of mythical human-cat hybrids, and cursed to transform into a deadly panther whenever she feels passion. Oliver laughs this off as superstition and marries her but when she refuses to consummate things, fearing what will happen, he eventually convinces her to see a psychiatrist who is convinced that it is all in her head. The thing is, her condition may well be real after all, putting her, Oliver and Alice (Jane Randolph), the co-worker that an increasingly frustrated Oliver has been turning to, in danger.

Instead of doing a straightforward remake of the original story, Schrader and screenwriter Alan Ormsby (whose script was given an uncredited rewrite by Schrader) took the basic premise of a woman convinced that she would turn into a panther upon feeling sexual desire, and spun it out in weirder and freakier ways that would have unimaginable in 1942. This time around, the story opens with Irena (Nastassja Kinski) arriving in New Orleans from Canada to reconnect with her brother, Paul (Malcolm McDowell), whom she hasn’t seen since they were orphaned and separated as kids following the suicides of their circus performer parents.

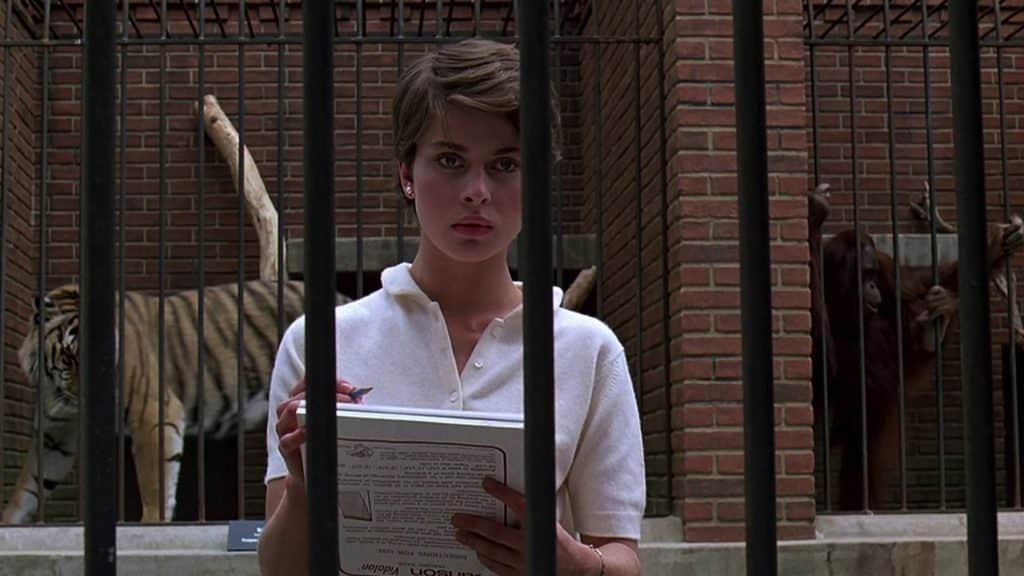

Shortly after Irena’s arrival, Paul mysteriously disappears. While waiting for his return, Irena visits the zoo and is drawn to its latest addition, a black leopard recently captured in a sleazy motel after mauling a prostitute. There, she meets Oliver (John Heard), the zoo curator who, instantly bewitched by Irena, offers her a job in the zoo’s gift shop. As it turns out, the leopard in custody is actually Paul, and when he eventually breaks free, he returns to Irena and reveals their dark family history. They are the descendants of a race of cat people who turn into leopards after having sex with humans, can only change back after killing a person and who can only safely mate with their own kind.

When Cat People went into production, Universal Pictures was presumably hoping for a classy and upscale horror film that would exploit a familiar title. By hiring Schrader to direct, they were undoubtably looking for the same kind of sleek visual style as his previous film, 1980’s American Gigolo. For Schrader, who was directing a project not written by him for the first time, it marked an opportunity to do a straightforward genre piece that would theoretically expand his range as a filmmaker. Needless to say, neither quite accomplished those goals as Schrader wound up making a film as deeply personal as anything in his filmography to that point ,and Universal ended up with a decidedly adult-skewing fairy tale.

While the Tourneur version was justifiably praised for utilizing a subtle approach to its fantastical premise—one so restrained that it could be argued for most its running time that the supernatural elements are all in Irena’s head—this version of Cat People lets it all hang out in increasingly startling ways. While Schrader shows some restraint in regards to the expected transformation sequences—there is only one major one to be had and isn’t nearly as detailed as similar scenes in such films of the time as An American Werewolf in London—there is plenty of blood on display here, most notoriously in the sequence when another zookeeper (Ed Begley Jr.) ends up losing an arm to Paul in his feline incarnation. There are only really two scenes in the film that qualify as being genuinely suspenseful—one in which a pursuit of Alice (Annette O’Toole) by an unseen entity is interrupted by a well-timed bus, and one where Alice is later menaced while swimming in a seemingly deserted pool late one night. It’s probably not a coincidence that these are, with one exception, the only times that the film explicitly references its predecessor.

This go-for-baroque spectacle was an outlier when it first came out 40 years ago and that feeling remains undiminished to this day.

Schrader was clearly more interested in using the project as a way to explore the ideas of desire, sexual obsession and doomed relationships in a more frankly mythological manner than in his scripts for Taxi Driver and Obsession, or in previous directorial efforts like Hardcore and American Gigolo. With the help of cinematographer John Bailey, visual consultant Fernando Scarfiotti and composer Giorgio Moroder (all of whom had worked with him on American Gigolo), not to mention the New Orleans locations, he was able to create a sensual dreamlike atmosphere, giving everything an unmistakable erotic haze. As for the sexual material, Schrader goes pretty far for what was permissible in a mainstream film back then. His depiction of barely contained lust finally exploding into a flurry of full-frontal nudity and kinks ranging from incest to bondage to even a potential hint of bestiality would almost certainly warrant an NC-17 rating in this comparatively restrained age.

On paper, this all admittedly sounds absurd so it is kind of astonishing to see how Schrader manages to present this outrageously lurid material in a serious and seriously sensual manner that prevents it from flying off the tracks into complete silliness. Yes, the story is nuts and contains a lot of stuff that simply doesn’t add up (especially in regards to Ruby Dee, who turns up briefly as Paul’s housekeeper) but that doesn’t really hurt things because Schrader is clearly not interested in such things. Instead, he is using the notion of Irena’s sexual awakening as an excuse for frankly going for a more mythical feel here with grim logic pushed to the side for a kind of sensory overload meant to mirror her late-blooming descent into her sexuality and the overwhelming feelings it creates in her.

Beyond the technical delights of the film (which hold up extraordinarily well after 40 years), the key reason for the success of Cat People is the almost unearthly presence of Nastassja Kinski as Irena. At the time she made this film, she was arguably one of the biggest sex symbols in the world and had directors as varied as Francis Ford Coppola, James Toback, and Jean-Jacques Beineix clamoring for her services. It is hard to imagine another actress of that period (or now, frankly) who could have conjured up the hypnotically potent blend of innocence and erotic heat that she generates every time she appears on the screen. Watching her, it is hard not to feel the sort of mind-scrambling obsession that she generates in both Oliver and Paul (not to mention Schrader himself) that helps to ramp up the perversity even further.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a film as nakedly bizarre (as well as just plain naked) as Cat People was probably never going to find favor with the masses. Indeed, when it opened in theaters, genre fans rejected it because it looked too much like an art film for their tastes, while the more sophisticated audiences who might have embraced it stayed away under the belief that it was just another shitty horror film. Many (but not all) critics incorrectly dismissed it as just another soulless remake, as they would a couple of months later with John Carpenter’s The Thing. The most overtly successful thing about it would prove to be the theme song contributed by David Bowie, which would later be recycled in both Inglourious Basterds and Atomic Blonde.

Even today, Cat People is probably too weird and overtly sexual to ever be fully embraced by viewers. For those who’ve succumbed to its spell, however, it continues to weave a gloriously Dionysian spell that both arouses, and captivates. If a new Cat People remake were to be made today, it would almost certainly be reduced to PG-13 pablum, but there was once a brief moment when such a thing was indeed possible. Those who prefer their cinematic fantasies to be of the decidedly unshackled variety (so to speak) will always be able to embrace the vision by Schrader, that most tortured of cinematic romantics, that captures amour at its most plus fou.