True love never dies in John Carpenter’s faithful adaptation of Stephen King’s killer car novel.

Every month, we at The Spool select a filmmaker to explore in greater depth — their themes, their deeper concerns, how their works chart the history of cinema and the filmmaker’s own biography. This month, we ring in the release of It: Chapter Two by exploring the various adaptations of the master of horror, Stephen King. Read the rest of our coverage here.

Stephen King is excellent at world building, and finding horror in the mundane. Where he struggles a bit is in portraying characters that aren’t small-town straight white men. He doesn’t write gay characters well — observe Don Hagarty, lover of the doomed Adrian Mellon (just that name alone is cringe-worthy), whose murder starts the final cycle of death in It. Hagarty is described as wearing both sparkly eye shadow and tight satin pants, and his weeping over his boyfriend’s brutal attack is viewed with distaste by Derry’s stereotypical stoic cops.

He’s also not very good at writing black characters — observe Odetta Holmes, one of the protagonists of the Dark Tower series, whose alternate personality, Detta Walker, speaks in an appalling ghetto patois. Eventually the two personalities become one to create the markedly improved Susannah Dean, but the passages involving Detta, who often refers to the other characters as “honky mahfahs.” are a bit of a slog. It’s not that King intentionally writes some of his characters as racist or homophobic stereotypes, it’s that his deep New England Baby Boomer background made it so he rarely encountered people who didn’t look or sound like him.

What King does write well — what he knows, given what he’s written about his own youth — are bullied outsiders. He captures that sense of being constantly on guard, looking around every corner for fear that your tormentor might be waiting for you. He gets that feeling of despondency, betrayal, and, yes, rage that comes from not being allowed to simply exist. Sometimes, in the case of It, the losers save the day. Other times, like in Carrie and Christine, they become tragic monsters, their repressed fear and anger resulting in a body count, and taking them along with it.

Christine’s Arnie Cunningham is a spiritual brother to Carrie White. Both of them are outcasts largely because they’re not one of the “beautiful people” (and how many of us were in high school?). Neither of them get much more warmth or affection from their parents than they do from their peers. Both of them experience a brief taste of feeling “normal,” until it’s taken away from them in an act of breathtaking cruelty. Both of them end up victims of their own rage, but not before weaving a path of destruction that those who survive it will never forget.

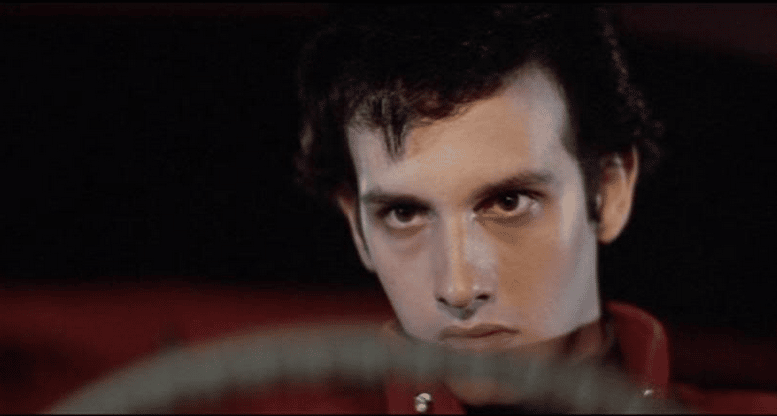

The film adaptation of Christine, directed by John Carpenter in 1983, was at least as solid and faithful as that of Brian De Palma’s adaptation of Carrie, and yet both the book and film are often overlooked. That’s a shame, because it’s a tightly paced, unsettling, and strangely sad story about evil and weakness coming together with horrifying results. Like Sissy Spacek in Carrie, you find yourself both repulsed by Keith Gordon as Arnie, and wishing someone would just give the damn kid a hug.

Though the film initially plays a little too hard into nerd stereotypes, right down to the adhesive tape holding Arnie’s glasses together, he’s portrayed a bit more kindly than other films in the same era. That was the funny thing about the nerd stereotype in 80s and 90s pop culture: even if nerds were portrayed as victims of bullying, it was clear that the filmmakers hated them at least as much as the other characters did. There was a sense that while what happens to them isn’t nice, they sort of deserve it too, for not knowing how to dress cool, for having dumb interests, for having the audacity to try to breathe the same air as their betters. This is why, in many cases, their lives don’t improve until they start looking and acting “normal.” Christine, of course, turns that concept on its head — Arnie eventually starts dressing and acting “cool,” but in a creepy, artificial way that the people who know him well find repellent. They know it’s not really him, and, indeed, it isn’t.

The kind of symbiotic, soulmate love Arnie and Christine have for each other is a rare thing.

Arnie’s just trying to live his life, and school bully Buddy Repperton (William Ostrander), who looks 30 years old, and his gross toadies refuse to leave him alone. At least he has one person in his corner, his best (and only) friend, Dennis (John Stockwell). Dennis, a handsome football player, would seem to be an unlikely friend for the awkward, unpopular Arnie, but there’s a warmth and genuineness to their relationship that provides the film’s surprising emotional core. Like losing someone to drug addiction, Dennis is distraught at the changes in Artie’s personality, and never gives up on trying to save him, even when Arnie mocks his concern. He doesn’t need Dennis anymore. Not when he has Christine.

The kind of symbiotic, soulmate love Arnie and Christine have for each other is a rare thing. They’ve been waiting for each other, and the moment they come together they’re like two flowers finally turning towards the sun – although in this case they’re corrupted flowers, their petals pocked with disease. Christine is powered on pure evil, and she taps right into the dark place in Artie’s heart that harbors all the resentment and hatred he feels for his bullies, his parents, and maybe, a little, even for Dennis, possibly the only person who truly cares about him.

There’s also Leigh (Alexandra Paul), for a little while at least. It’s Christine that gives Arnie the confidence and swinging dick swagger to ask his pretty new classmate, on a date. That’s his taste of normalcy for a little while, getting to drive a cool car with a beautiful girl at his side, until it becomes apparent that Christine demands to be the only woman in his life. When Leigh nearly chokes to death in Christine, Arnie is almost comically ineffectual in trying to save her. It’s unclear if he’s just frightened, or if something is holding him back. In any case, he won’t make that mistake again. After that, it’s just him and Christine.

The closer we get to the climax of the film, the more Arnie looks like he’s being bled by a vampire. But he loves it, he needs what he and Christine have. “Let me tell you a little something about love, Dennis,” he says. “It has a voracious appetite. It eats everything. Friendship. Family. It kills me how much it eats. But I’ll tell you something else. You feed it right, and it can be a beautiful thing, and that’s what we have. You know, when someone believes in you, man, you can do anything, any fucking thing in the entire universe. And when you believe right back in that someone, then watch out, world, because nobody can stop you then, nobody. Ever.”

Arnie feeds Christine his heart and soul, and she in turn rights the wrongs in his life, while convincing him that everyone, even those who care about him, secretly mean to do him harm. One scene that suffers in the transition from book to screen is the climactic battle in which Dennis and Leigh team up to destroy Christine. In the movie, until he’s thrown through the windshield and killed, Arnie is at the wheel of Christine. In the book, he’s not there at all — Dennis later finds out that he was killed in a separate car accident with his mother, and that he was spotted struggling with a mysterious third party inside the vehicle, perhaps making one last stand to save his soul from the spirit that powers Christine.

Changing that aspect removes some of the tragedy of the story, but the outcome is the same: Christine and Arnie’s love is eternal, and if she can’t have him, no one can.