Read also:

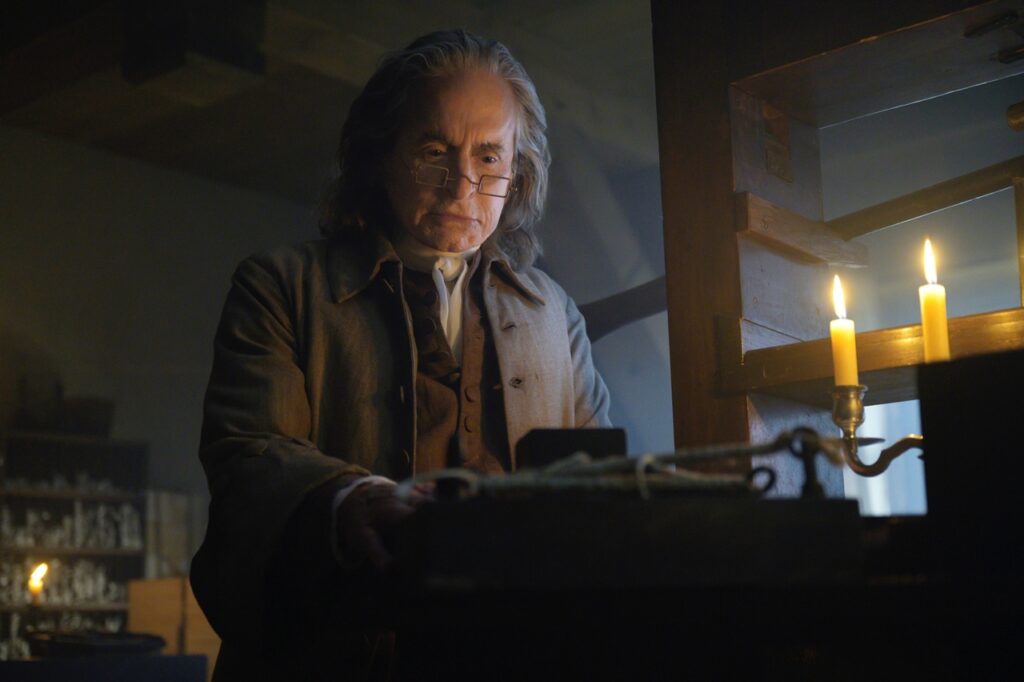

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableMichael Douglas’s career so deeply connects him to as specific kind of late 20th/early 21st Century man. As a result, throwing him back to the 18th Century and into the body of Benjamin Franklin feels deeply counterintuitive. It is not surprising that Franklin—an adaptation of the book A Great Improvisation by Stacy Schiff—is one of the few period projects Douglas has done, joining the likes of The Ghost and the Darkness and those flashback scenes in the Ant-Man films. What is surprising, and to the series’ credit, is how quickly that strangeness recedes. It isn’t that Douglas manages to fade into the role of Franklin until he disappears entirely, but he does manage to recede enough that he doesn’t disrupt the show’s reality.

In some ways, Douglas proves a surprisingly apt selection. No stranger to playing womanizers on screen, Douglas easily finds the correct valence to portray Franklin’s specific flavor of late 18th-century skirt chaser. The metacommentary works in his favor as well, an aging icon who retains much of his skill but perhaps can no longer command the same buzz or box office returns embodying an aging icon whose mind remains sharp but whose body—and possibly will—has been beaten up by life and time. While almost a decade older than the Franklin he’s portraying, Douglas also excels at the moments where the audience witnesses the statesman energized like old times.

Still, the script too frequently hamstrings the actor. Not bad by any means, the writing still suffers for trying to match Franklin’s reputation. It’s the old conundrum of trying to build a series, film, or play around a singular piece of art. How does a creator convince the audience that someone is singing the most fantastic song ever without truly writing the most fantastic song ever? Similarly, how do writers provide dialogue to what is, by historical reputation, one of the greatest wits in American History without simply quoting his greatest hits?

Douglas invests a slyness in Franklin that hints at his talents, overcoming some of those script deficiencies. Nonetheless, it is a bit akin to telling, not showing, in the end. On the other hand, the source material was similarly criticized for its inability to make Franklin come to life on the page. On this score, the series fares a fair bit better. Even if the script can’t always find the words, it at least frequently confirms how the man earned his reputation.

The supporting cast is a mixed bag. Some, like Eddie Marsan’s John Adams, prove near perfect. Marsan’s depiction of Adams’ rigidity and love of country make it clear his unpleasantness and decency. Thibault de Montalembert as foreign minister Count de Vergennes gives the French side of the story a grounding that the series too rarely affords the host country’s citizens. Too often, Franklin seems both overly dazzled and repulsed by the French upper class’s excesses, a condition that renders them more cartoonish than characters.

Other supporting players are interesting but ultimately incomplete. Ludivine Sagnier, as potential married love interest Madame Brillon, gives her character far more depth than the script affords her. She finds many ways to portray sadness and regret with only a look or cadence. Still, she remains frustratingly ill-defined. Edward Bancroft (Daniel Mays), Franklin’s doctor and confidante, is in a similar situation. He’s a thin character embodied by an actor doing tremendous work to push Bancroft into three dimensions.

Finally, there is Franklin’s grandson Temple (Noah Jupe). The series has seemingly elected him to carry all possible shifts in mood and motivation while Douglas remains steadfastly wily. As a result, Jupe frequently feels like he’s playing different characters, often within the same episode. More tiresomely, he—and thus, the viewers—frequently finds himself on the receiving end of several lessons from “perhaps the French aren’t all that great” to “perhaps rich people aren’t all that great” and, most frequently, “perhaps my famously intelligent and witty grandfather might be intelligent and witty.”

With so little to hold on to, it’s no wonder Jupe’s Temple feels so immature and unpleasant. Present-day 19-year-olds would not seem so naïve. A 19-year-old, during a time when, effectively, there was no societal difference between teens and adults, has even less of an excuse to so thoroughly and repeatedly demonstrate such immaturity. Jupe, a talented performer, deserves better.

While there is a lot of Temple, he’s ultimately not the titular Franklin. Thus, regardless of the character’s shortcomings, the series largely moves past and over him without much by way of derailment. The number of episodes and their running time do far more damage. There’s plenty to enjoy visually alongside the aforementioned strong performances, but Franklin’s pace still leaves much to be desired. It has a churning, repetitive cadence. That may accurately portray the grind of Franklin’s years in France securing the country’s relationship with the fledgling United States. However, from an entertainment standpoint, it makes for sluggish viewing.

In the end, Benjamin Franklin’s mix of merits and flaws made him such a compelling historical figure. Unfortunately for Franklin, its ratio of virtues to defects leans too heavily to the latter.

Franklin fires up on the printing press on AppleTV+ beginning April 12.