Read also:

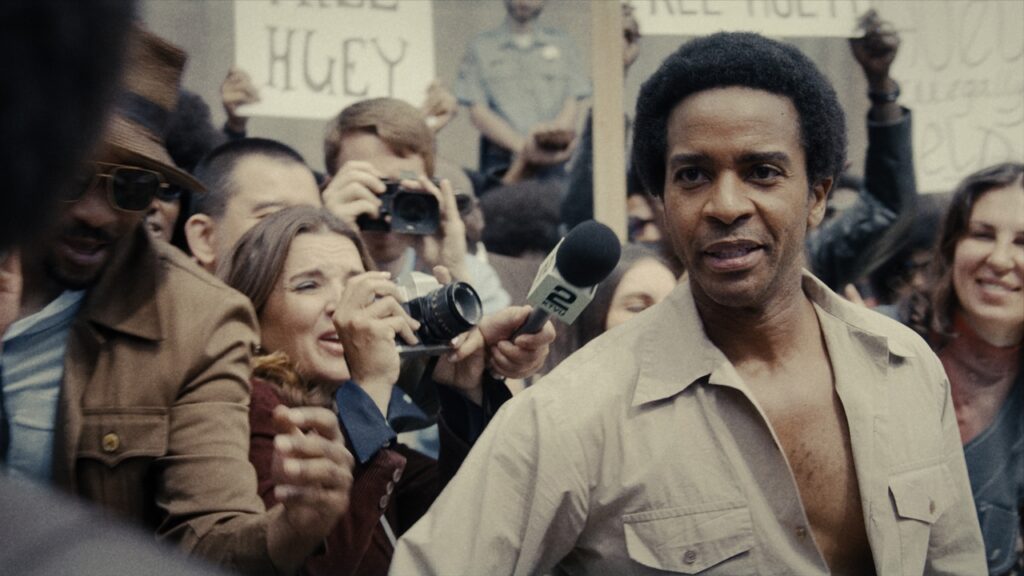

How to Watch FX Live Without CableHow To Watch AMC Without CableHow to Watch ABC Without CableHow to Watch Paramount Network Without CableA frequently offered solution to the problem of stale biopics involves ditching the cradle-to-the-grave format. Instead, focus on a specific era or significant event in the life of an important figure. Let that story define viewers’ understanding of the person, giving the audience an insightful perspective without the exercise of box-checking. The Big Cigar takes this advice, narrowing its vision of Huey P. Newton (André Holland) to (mostly) 1974. That year, Newton faced multiple criminal charges and became increasingly convinced the government was targeting him for more than arrest. In response, the Black Panther Party co-founder left the U.S. for exile in Cuba.

Joshuah Bearman’s Playboy essay gives co-creators Janine Sherman Barrois and Jim Hecht a fascinating launching pad for The Big Cigar. It’s not difficult to understand why Newton’s Hollywood-fueled escape just ahead of the FBI’s clutches would be a draw. Unfortunately, in adapting it for television, the creative team’s tonal and structural choices undermine the series.

Hecht, coming off his work on Winning Time: The Rise of the Lakers’ Dynasty, seems to have brought over some tonal impulses from his collaborator on that project, Adam McKay. As a result, The Big Cigar frequently tries to balance humor with dead serious topics like possible political assassination, government-orchestrated harassment, and gun violence. While the show manages those tonal juxtapositions better than McKay’s disastrous Don’t Look Up, it never delivers as well as The Big Short. Several jokes land without feeling disrespectful of the series’ more earnest moments or themes. Unfortunately, it is never as funny as it wants to be. That frequently creates a gulf between its humorous and solemn moments. They can’t seem to get both sides to integrate satisfyingly.

Also undermining that effort is to tell the story in a non-linear fashion. While the story centers on the events of 1974, The Big Cigar frequently breaks away from its present to look back on other moments in Newton’s life and the story of The Black Panthers. Holland can adequately handle any acting challenge the show levels, but the time jumps make for a disjointed portrait of the activist. As a result, it becomes difficult to connect each aspect into a cohesive whole. The series gives us facets of the man—his early days’ optimism, his stubbornness, the moments where drug use and paranoia seemingly leave him paralyzed in place—but never a three-dimensional person.

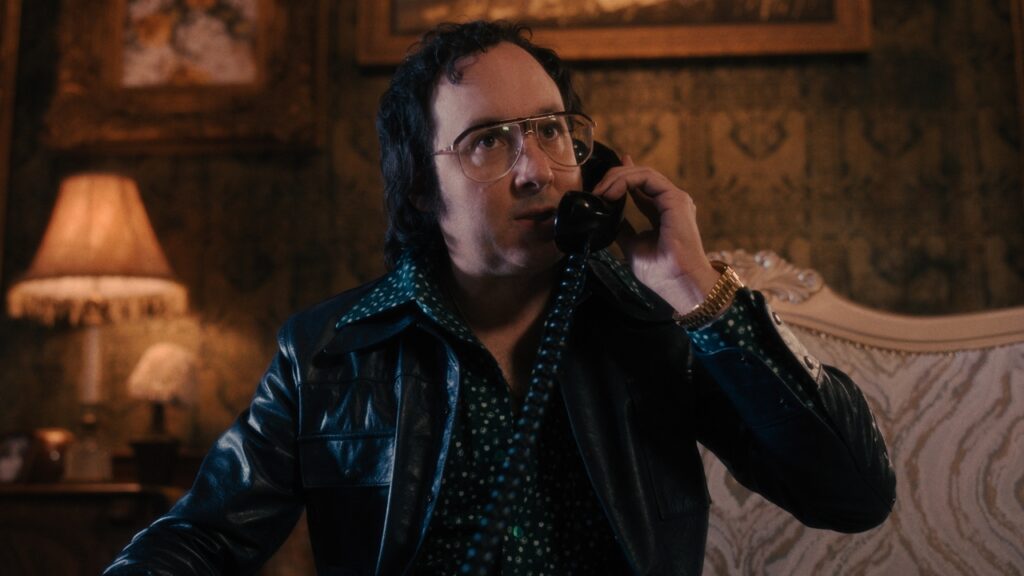

Bert Schneider (Alessandro Nivola) fares better, but he’s also a significantly less complicated character. Nivola invests him with an easy charisma that helps the audience understand why such an obviously self-sabotaging individual could persuade so many people to follow his plans. What the series never quite manages is to make it clear if Bert’s declaration that Newton is his best friend is accurate or yet another example of the producer fooling himself. His longtime friend and business partner, Steve Blauner (P.J. Byrne), gets juicier material because Blauner does have an arc moving him through the events.

Much like Newton trapped in his friends’ house seeking some means of escape, The Big Cigar does wear out its welcome over the course of six episodes. Part of this is the nature of the actual events. The plan to get Newton out of America and into Cuba encountered several obstacles, requiring people to reset and alter their approach. That’s true to the history, but from a dramatic standpoint, it becomes repetitious. The previously noted structure makes that sense of “haven’t we done this before” worse by taking the audience away to the late 60s during one failed attempt only to deposit them back in the midst of another. It isn’t confusing, but it is monotonous.

What ends up hurting The Big Cigar most is it never sells viewers on the importance of this escape over other years or events in Newton’s life. Why is this the story that needs to be told about Huey P. Newton? It is intriguing, to be certain, but the show feels as though it is reaching for something more than “this is an absorbing, little-discussed part of history”. Sadly, it never convincingly finds it.

From history, we know Newton returns to America after a few years of exile, faces the charges, and is vindicated. We know the Panthers were never the same, but the show lays out ample evidence that by 1974, that process was already well underway. The one direct result is, arguably, Schneider and Brauner’s final collaboration, the Vietnam War documentary Hearts and Minds. It went on to win an Oscar giving Schneider the platform for one of the Academy Awards’ more controversial speeches. However, the moment receives footnote treatment in the series’ final moments.

Even that is a problem, though. This should be the story of a Black activist and his inner circle fighting against the cost of being themselves in America after what was billed as the triumph of the Civil Rights Movement. In practice, however, the series struggles to keep its spotlight on Newton. Despite Holland’s excellent work, The Big Cigar keeps wandering away from him. Instead, it showcases Bert’s difficulties with his brother (Noah Emmerich) or namedrops another Hollywood type. Even when those moments provide Chris Brochu’s entertainingly toasted take on Dennis Hopper, it’s difficult not to be frustrated. Why should Hopper get a more memorable scene than Newton’s eventual wife, Gwen (Tiffany Boone)? When Boone finally gets material to work with, it makes her relative absence further disappointing.

The instinct to tell this story is good. It has plenty of compelling characters and moments of shocking violence. It offers an honest and grim look at how ready the government was to suppress and eliminate black activists. By trying to weigh down the story with something bigger than those (already quite large) themes, though, The Big Cigar achieves the opposite effect. In this telling, the story loses power and resonance. The original essay—and Newton—deserve a stronger adaptation.

The Big Cigar lights up with AppleTV+ on May 17.