Lambasted at the time for being too shallow about race, HBO’s animated short takes on new significance in a post-BLM America.

In light of the death of George Floyd, and the eruption of race-provoked civil unrest within the United States, many are looking to Black media and Black storytelling to not only diversify their media consumption but to more deeply feel the long-standing systemic racism being combated by the protests and civil action over the last couple of weeks.

While that often takes the form of curated Letterboxd recommendation lists of recent critically-acclaimed films like Selma, If Beale Street Could Talk, and 13th, one of animation’s most obscure curios has now been thrust into relevancy: 1994’s HBO animated short film Whitewash, which was critically lambasted at the time but now feels like a powerful snapshot of the racist attacks that have been the focus of the national consciousness.

Directed by Michael Sporn, Whitewash (based on horrific true events that took place in New York) tells the tale of Helene Angel (Serena Henry), a Black 4th grader from the Bronx who is accosted by a white gang. The gang hurls racial epithets at her and her brother Mauricio (Ndehru Roberts), who are trying to walk home from school. Mauricio flees the encounter with a black eye, while Helene Angel is assaulted both physically and psychologically when one of the gang members sprays her face with white shoe shine polish.

The rest of the film deals with the emotional fallout of the race-based attack. The media stake out in front of Helene Angel’s home, and she becomes too frightened to return to school. Eventually, her classmates come to visit and let her know that they miss her and that she’s not alone.

The film has not aged particularly well. The simplistic art style makes Whitewash resemble a storybook brought to life, but for HBO it comes across as cheap and amateurish.

The acting is stilted and leaves a lot to be desired (with the exception of an impassioned performance by late actress and civil rights activist Ruby Dee, who plays Helene Angel’s grandmother). This is especially apparent at the linchpin moment of Whitewash when the gang members surround Helene Angel and her brother and call them the N-word (even the actors sound noticeably awkward and uncomfortable with the exchange). Later in the special, it’s as if someone placed a camera in the middle of an actual classroom and recorded children’s candid responses for the audio. It’s at least earnest, if not exactly polished.

At the time of its initial airing, Whitewash faced middling reviews. In a review of the short, Los Angeles Times animation critic Charles Solomon accused the special of failing to delve beneath the surface on race issues, and not being interesting enough to leave any meaningful impact on viewers.

In hindsight, Whitewash’s anti-racist messaging is well-intentioned, albeit a bit tone-deaf. Despite speaking to events affecting Black people, with a screenplay written by the late African-American playwright and feminist Ntokaze Shange, the directorial credit for Whitewash belongs to Sporn, a white man.

Sporn wasn’t known for his revolutionary views on hard-hitting issues. Most of his previous credits are for animated adaptations of popular children’s books; though he received critical attention for his work on Doctor DeSoto and Abel’s Island, earning him a spot on the short list for an Oscar and a Primetime Emmy, respectively. Still, the choice of Sporn is disappointing, considering how many Black creators at the time may have been eager to take the helm of this project (Bebe’s Kids director Bruce W. Smith comes to mind).

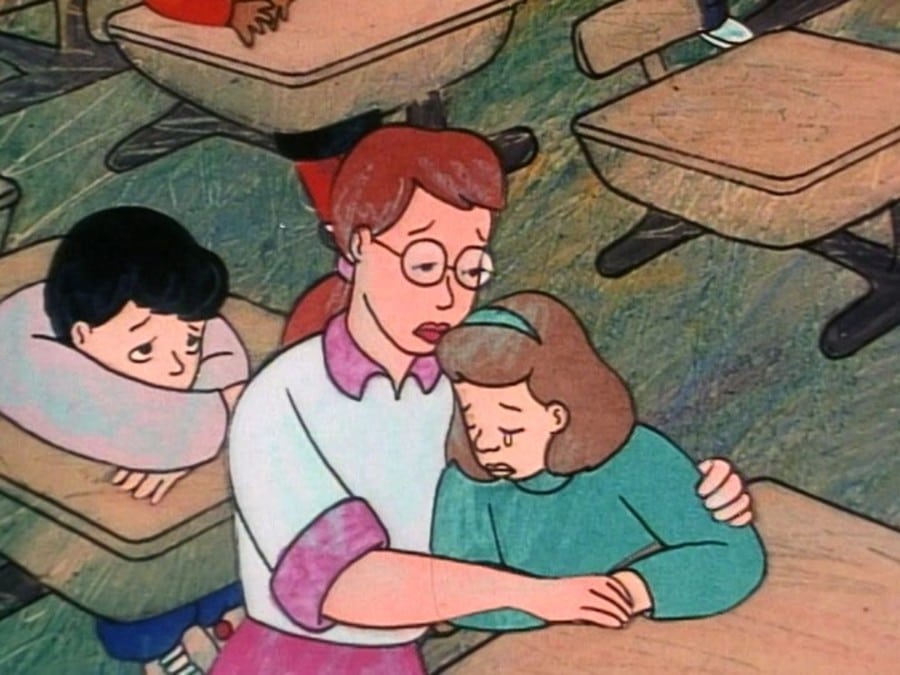

There are certain scenes in Whitewash that don’t sit well with repeated viewings. At the special’s emotional climax, it is a white classmate that breaks down in tears when Helene Angel’s name is called for attendance. The classmate is subsequently comforted by a white teacher (Linda Lavin), centering their emotions instead of the victim’s.

And the ending does little to satisfy the viewer. Yes, Helene Angel is bolstered by her friends’ support and returns to school, but the gang who attacked her is never brought to justice, nor do they atone for their actions. By the time the credits roll, it’s to be assumed that the people responsible were never punished. (In fact, in the case of the real life hate crimes upon which Whitewash is based, no arrests were ever made).

In the third act of Whitewash, Helene Angel’s grandmother attempts to assuage her granddaughter’s fears by recounting her own experiences with racism. “Those boys hurt you,” she explained, “but they are the ugly ones. You have to see that and always remember that”. The scene is interlaced with imagery of Black people in the South during segregation, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and an excerpt from his “I Have a Dream” speech.

The fall of segregation seemed unheard of in the ‘60s, yet the dream was realized. Likewise, a Black president must have seemed like a pipe dream to many in the ‘90s, yet the world had the privilege to witness Barack Obama become the 44th president of the United States.

Fast-forward to 2020. There are nationwide protests happening for George Lloyd and other Black victims of police brutality. It’s curiously poignant that the references Whitewash makes to urban style and culture are dated by modern standards. Yet the plausibility of such hatred, such anti-Black sentiment and violence, is still very much relevant.

Here lies the grand irony highlighted by Whitewash: although so much progress has been made for Black people in the States and around the globe, in many ways, very little has changed at all.

Whitewash was lambasted at the time for not having a stronger message in the face of racism. Today, its quiet, understated wisdom speaks volumes on what Black Americans continue to endure on a daily basis.

Whitewash was lambasted at the time for not having a stronger message in the face of racism. Today, its quiet, understated wisdom speaks volumes on what Black Americans continue to endure on a daily basis.

Whitewash premiered three years after Rodney King was beaten by police, kicking off the ’92 LA riots. And now, history repeats itself in Minneapolis. This time, the outrage stems from a Black man having his life snuffed out at the hands of a police officer, recorded on camera for all to see. This time, the scope of dissent has grown so wide that protests have broken out in all fifty states and even in other countries around the world.

To ignore the existence of racism — to fail to acknowledge how white supremacy permeated society and fed into the unrest and frustration that has manifested itself into Black Lives Matter and other anti-racism groups — is to repeat history over and over again.

For this reason, Whitewash should not be allowed to vanish from the collective conscience again. Those who may have missed the special in the ‘90s may find it worth the purchase as a teaching tool. It should be used to open a dialogue on what needs to be done in order to heal our ailing nation and to educate future generations about white privilege and the anti-Black racism that takes place within society.

Whitewash is available to stream on Amazon Prime Video, and to own digitally for less than five dollars on Youtube and Google Play.