Kidney transplants, Satanism, representation, and more come to a head in the festival’s documentary slate.

(This dispatch is part of our coverage of the 2023 South by Southwest Film Festival.)

One of the joys of the South by Southwest Film Festival (even when, like me, you’re covering remotely because Austin is expensive, y’all) is that, even within the often-dry documentary offerings on display, you’ll find some quirky, offbeat works from idiosyncratic filmmakers on subjects you may not expect. That’s certainly true in this year’s Documentary Spotlight program, where I saw quite a few films that used deeply personal stories to tackle bigger, thornier questions about our place in our societies and our universe. Plus, Satan shows up!

This time, though, Satan doesn’t come to us courtesy of Hail Satan? filmmaker Penny Lane; no, her latest in the fest is one of her most experimental and thoughtful to date, not least because the filmmaker turns her curious, darkly funny eye right back on herself. In 2019, the filmmaker decided, apropos of nothing, to become an altruistic, or “Good Samaritan,” kidney donor: a most unusual kind of organ donation, since a stranger is giving up one of their organs to a complete stranger. Why would she do that? Lane doesn’t even know, not really. Thus we have Confessions of a Good Samaritan, a funny, thought-provoking, and refreshingly honest look at the double-edged sword of good deeds.

Lane’s films often tackle the thorny complexities of social perception — the gulf between how other people see you and how you see you. Confessions is no different, but this time, the subject isn’t a dead conman from a hundred years ago (Nuts!) or a musical maestro whose success clashes with his critical reception (Listening to Kenny G). It’s Lane herself, making a documentary about her upcoming kidney donation while constantly questioning why she’s both donating her kidney and making a documentary about the process at the same time. Is it to feel like a good person for doing it? Is it to tell others to do the same?

Along the way, she branches out to discuss the nature of charity, interviewing scholars, neuroscientists, and even other altruistic donors to figure out why we do things for others. They all extol the virtues of those who give their time, energy, and actual flesh of others, even congratulating Lane from across the invisible line between subject and interviewer for her impending sacrifice. But then, Lane will cut back to herself, jotting down her neurotic thoughts about every detail of the procedure (testing, assigning medical proxies to make decisions in her stead) in her MacBook. It’s a remarkably vulnerable approach, Lane testing herself to see just how much of this decision is based in a desire to be seen as a good person, a “Good Samaritan”…. and whether that really matters at the end of the day.

Occasionally, Lane (and some of the other donors she interviews) express hope that the doc will serve as advocacy for other altruistic donors to go under the knife. After all, there are 100,000 patients on donation waiting lists at any given time, and not enough kidneys to go around. But Confessions doesn’t feel like a pat PSA for Good Samaritanism; it’s an interrogation of the nature of altruism itself, and why we might help someone else even if it causes us intense mental and physical anguish.

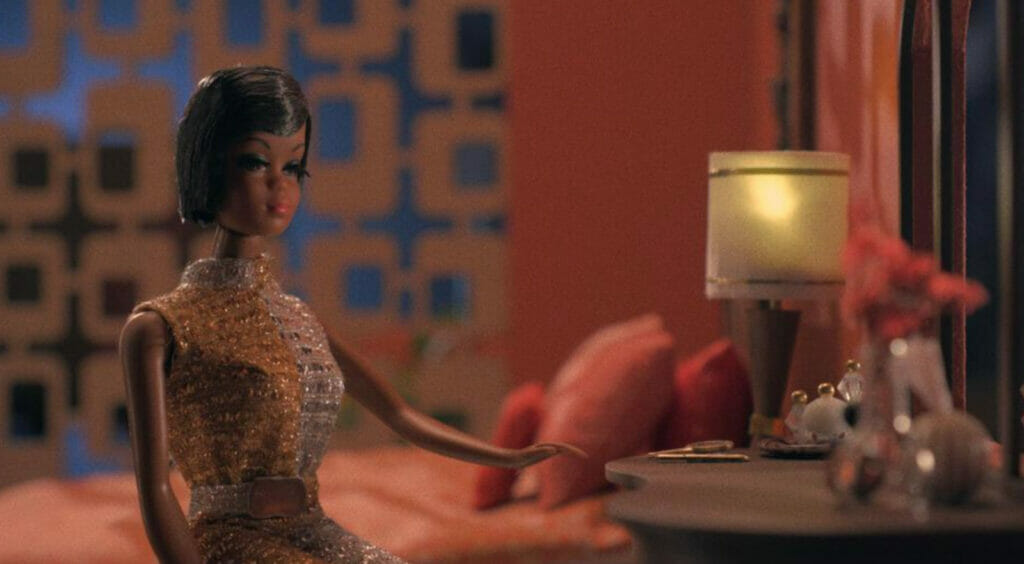

Another look at the societal through the personal comes in Lagueria Davis‘ debut, Black Barbie: A Documentary, a fun, multifaceted exploration of the history of Black Barbie dolls and how they fit in the ever-complex nexus of representation politics. Davis was never the kind of girl to play with Barbies growing up, but when she discovered that her aunt, Beulah Mae Mitchell, was an employee for Mattel and allegedly gave Mattel co-owner Ruth Handler the idea for a Black Barbie, she decided to make a doc about her — the doll herself, the Black women who pioneered her, and just how groundbreaking a Black Barbie doll can really be.

In so doing, Davis delves into complicated questions about the value of representation in the history of toys — Black Barbie, after all, did offer tangible hope and aspiration for generations of Black girls who hoped to see dolls that looked like them, especially considering how Black dolls of the past tended towards coal-black minstrelsy. Black Barbie excels when it’s charting this history, both at Mattel (interviewing other Black women who were instrumental in her design, like Kitty Black Perkins and Stacey McBride-Irby) and elsewhere (the Shindana Toy Company, which specialized in realistic, aspirational Black toys). There’s a clear reverence for Black Barbie’s role in actualizing generations of young Black girls, and the value of seeing themselves in the toys society gives them to play.

But there’s a danger to laying Black liberation squarely on the feet of Black Barbie, and Davis’ doc is most insightful when it gestures toward those limitations. As much as it pats Mattel on the back for putting the doll out in the first place, the doc occasionally points out the marginal, tokenized status Black Barbie and other African-American members of the Barbie family have in Mattel’s universe. She’s rarely, if ever, spotlighted as the lead, and if she is, it’s in painfully tone-deaf vlogs to try to teach kids about racism in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests (and hollow corporate reckonings) that followed George Floyd’s murder by police in 2020. Mattel’s involvement in the doc is limited, and Davis seems to relish in twisting the screws on the one poor DEI flack they allowed to participate, asking him the hard questions the higher-ups refuse to answer.

Black Barbie does suffer from some dissonance, though, falling into a few representation-politics traps while also acknowledging that just putting a token Black face in the Barbie lineup won’t fix racism — no matter how many Black girls it inspires. “Don’t place onto Barbie the work we should be doing as a society,” one expert muses. “Until we’re doing the hard work, then we’re just playing with ourselves.” It feels like the most cogent point in the documentary, often otherwise lost in favor of the Black Girl Magic optimism the doc celebrates. That said, it’s an insightful look into the ways race factors into the economics of play, and how far we have to go to spotlight Black success beyond the commercial and capitalistic.

From bubbly celebrations of dolls to the rise of the Satanic Panic: Sean Horloe and Steve J. Adams‘ Satan Wants You charts the rise of the moral panics around Satanism that cropped up around the 1970s and ’80s. Specifically, the filmmakers dive deep into the movement’s arguable Patient Zero: Michelle Remembers, a best-selling memoir written by Michelle Smith and Dr. Lawrence Pazder, charting their therapeutic relationship as the latter helped the former dredge up allegedly suppressed memories about being used for Satanic rituals as a young baby. The book, and their accounts, were sensational — tales of bloody sacrifices and maternal neglect, the kind of over-the-top catnip that made their accounts fodder for daytime talk shows and scaremongering late-night news stories. Before long, the Satanic Panic was in full swing, and the nation was swept away with fears of the occult in everything from rock music to Dungeons & Dragons.

Horloe and Adams fall upon tried-and-true true crime doc formulas, from ominous music playing over archival footage to moodily-lit interviews with friends, family, and experts. We hear the terrifying audio of Smith and Dr. Pazder’s sessions over shots of rolling tape, hearing her agonized screams that “I don’t know what’s real anymore.” But as the doc digs deeper into their story, one of disturbing closeness between doctor and patient and the financial incentives to concoct such a wild yarn amid a culture desperate for a villain to panic about, Satan Wants You grows more than a little tedious. There’s no involvement from Smith (Pazder passed some years back), which feels a vital misstep; it would be nice to get her side of the story, to see if she still believes these things, or would even admit it on camera. Otherwise, it’s the same tropes you’ll see in any true-crime doc, with little to differentiate it.

Still, maybe the most important elements of Satan Wants You comes from its ability to link the panics of the past with the present: QAnon, anti-trans bills, scares about CRT coming for your school, it’s all grown from the same conservative DNA. It’s one thing to scoff at the silliness of the Satanic Panic, but it’s back in new, ever more violent forms. And we’d better pay attention this time.

Still, maybe the most eye-opening doc of the bunch is its most idiosyncratic: Ian Cheney‘s The Arc of Oblivion, a poignant look at our collective desperation to leave something behind after we’re gone, and what that impulse says about us as a species. Ostensibly, the doc is about Cheney’s efforts to build an ark in the middle of his parents’ farm in Maine just to store the many hard drives of digital footage he’s amassed throughout his life. But as we see that ark come together, plank by plank, Cheney takes many endearing detours to investigate the way nature records its own history — rings on trees, layers of rock caked atop each other over eons — and how we emulate those patterns in everything from physical media to the Arctic seed vault.

Cheney’s approach is warm and engaging, flitting between interviews with a host of colorful characters (including Werner Herzog himself, who produces and shows up late in the film to muse on the nature of impermanence) and stop-motion animated sequences. Transitions often come courtesy of a tiny portable TV Cheney places in unexpected settings, like rock faces, illustrating the link between the analog and the digital as twin mechanisms of memory that exist outside of us.

“You must spend your life making memories,” Cheney remembers his father telling him when he was young. The Arc of Oblivion explores that impulse to its fullest, a work marked by clear-eyed approaches to existential questions about the finite nature of human life, and our desperate attempts to extend it beyond our lifespans. Physical records can be destroyed, digital data breaks down after mere decades. Would a catastrophe wipe not just us, but our memory, off the face of the Earth? Cheney’s exploration of these ideas is endearing and eloquent, maybe the most thought-provoking documentary I’ve seen this year to date.

Read next: The Spool's Best New Releases

Streaming guides

The Best Live TV Streaming Services With Free Trial

The praises of live TV streaming services don’t need to be further sung. By now, we all know that compared to clunky, commitment-heavy cable, live TV is cheaper and much easier to manage. But just in case you’re still on the fence about jumping over to the other side, or if you’re just unhappy with ... The Best Live TV Streaming Services With Free Trial

How to Watch Power Book III: Raising Kanan Season 3

Season 3 of the hotly anticipated Power spin-off, Power Book III: Raising Kanan, is arriving on Starz soon, so you know what that means: it’s the ’90s again in The Southside, and we’re back with the Thomas family as they navigate the ins and outs of the criminal underworld they’re helping build. Mekai Curtis is ... How to Watch Power Book III: Raising Kanan Season 3

How to Watch Doctor Who: 60th Anniversary Specials

Ladies and gentlemen, we’re so back! To celebrate Doctor Who’s 60th anniversary, the BBC is producing a three-episode special starring none other than the Tenth/Fourteenth Doctor himself, David Tennant. And to the supreme delight of fans (that would be me, dear reader), the Doctor will be joined by old-time companion Donna Noble (Catherine Tate) and ... How to Watch Doctor Who: 60th Anniversary Specials

Which Netflix Country has Interstellar?

Maybe you’ve just seen Oppenheimer and have the strongest urge to marathon—or more fun yet, rank!—all of Christopher Nolan’s films. Or maybe you’re one of the few who haven’t seen Interstellar yet. If you are, then you should change that immediately; the dystopian epic is one of Nolan’s best, and with that incredible twist in ... Which Netflix Country has Interstellar?

Which Netflix Country Has Each Movie of The Hunger Games?

For whatever reason, The Hunger Games series isn’t available in the same countries around the world. You’ll find the first and second (aka the best) installments in Hong Kong, for instance, but not the third and fourth. It’s a frustrating dilemma, especially if you don’t even have a single entry in your region, which is ... Which Netflix Country Has Each Movie of The Hunger Games?

How to Watch ESPN With A Free Trial

One of the major concerns people have before cutting the cord is potentially losing access to live sports. But the great thing about live TV streaming services is that you never lose that access. Minus the contracts and complications of cable, these streaming services connect you to a host of live channels, including ESPN. So ... How to Watch ESPN With A Free Trial

How to Watch Paramount Network With a Free Trial

To date, Paramount Network has only two original shows on air right now: Yellowstone and Bar Rescue. The network seems to have its hands full with on-demand streaming service Paramount+, which is constantly stacked with a fresh supply of new shows. But Yellowstone and Bar Rescue are so sturdy and expansive that the network doesn’t ... How to Watch Paramount Network With a Free Trial

How to Watch WE TV With a Free Trial

Previously “Women’s Entertainment,” We TV has since rebranded to accurately reflect its name and be a more inclusive lifestyle channel. It’s home to addictive reality gems like Bold and Bougie, Bridezillas, Marriage Boot Camp, and The Untold Stories of Hip Hop. And when it’s not airing original titles, it has on syndicated shows like 9-1-1, ... How to Watch WE TV With a Free Trial

How to Watch Comedy Central With a Free Trial

It’s no coincidence that many of today’s biggest comedians found their footing on Comedy Central: the channel is a bastion of emerging comic talents. It served as a playground for people like Nathan Fielder (Fielder For You), Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson (Broad City), Tim Robinson (Detroiters), and Dave Chappelle (Chappelle’s Show) before they shot ... How to Watch Comedy Central With a Free Trial

How to Watch FX With a Free Trial

You’d be hard-pressed to find a bad show airing on FX. The channel has made a name for itself as a bastion of high-brow TV, along with HBO and AMC. It’s produced shows like Atlanta, Fargo, The Americans, Archer, and more recently, Shogun. But because it’s owned by Disney, it still airs several blockbusters in ... How to Watch FX With a Free Trial

How to Watch TNT Sports With A Free Trial

For many sports fans, TNT is a non-negotiable. It broadcasts NBA, MLB, NHL, college basketball, and All Elite Wrestling matches. And, as a bonus, it also has reruns of shows like Supernatural, Charmed, and NCIS, as well as films like The Avengers, Dune, and Justice League. But while TNT used to be a cable staple, ... How to Watch TNT Sports With A Free Trial