Welcome to the Criterion Corner, where we break down some of the month’s new releases from the Criterion Collection.

#1064: The Parallax View (1974), dir. Alan J. Pakula

Few filmmakers captured the feeling of absolute, overwhelming dread at the corruption of American governmental and societal systems in the ’70s quite like Alan J. Pakula. And while Klute (which has already enjoyed a robust Criterion release) and All the President’s Men tend to dominate that discourse, there’s also The Parallax View to think about — a movie that matches the flailing, doomsday energy of the others, even if it doesn’t quite reach their highs.

The film begins with the assassination of a United States senator, one which was quickly buried and might stay that way, if not for the efforts of a dogged, wearied newspaper reporter (played with dashing conviction by Warren Beatty) who’s picked up the scent and is ready to uncover the truth — especially after an old flame winds up dead. His investigation puts him in the path of the Parallax Corporation, which organizes illusory operatives to do all manner of dirty political biddings, regardless of affiliation. There’s no rhyme or reason to the killings, no grander plan; Parallax simply follows the money.

What follows is a crackerjack thriller as notable for its purposefully disorienting pace as it is Gordon Willis’ ink-black cinematography. Beatty’s Joe Frady follows one lead after the next, only to find himself barely escaping with his life, deadly situations landing on him one after the other. No one can be trusted; the few who can are well within the sights of your enemies. And the harrowing scope of Parallax’s capabilities puts Frady at a terrifying disadvantage, which Pakula dials up for maximum tension.

That said, it doesn’t have the same punch as President’s or Klute, the amorphousness of its central conflict giving you little to latch onto besides Beatty’s relatively two-dimensional investigator. The sequences still pack a wallop — an early sequence atop Seattle’s Space Needle and an agonizing chase in the rafters of an auditorium at the climax come to mind — but its social conscience is much more vaguely nihilistic.

It’s an attribute, strangely, that Nathan Heller’s essay for the Criterion set fails to pick up on, characterizing the film in its closing paragraphs as “being carried by hope” — a strange conclusion to draw, considering Frady’s bleak fate by the closing minutes of Parallax. It’s a sentiment drawn seemingly from the thought process that Pakula is showing us what not to do with our American experiment, and in so doing, paradoxically shows us a path forward; but that requires a lot of hoop-jumping that the nihilistic Parallax doesn’t warrant. It’s not begging us to do better; it’s just showing us what we’re doing wrong, and how bad that really gets.

Still, besides that flop of an essay, the film has a lovely 4k transfer that keeps Willis’ dark abysses and idiosyncratic compositions alive, and extras that include an introduction by Repo Man director Alex Cox and interviews with Pakula, Willis, and others. It’s not the most features-rich set in the collection, but it feels commensurate to Parallax‘s status as a piece of a larger whole, a film best viewed in the context of Pakula’s other conspiracy thrillers.

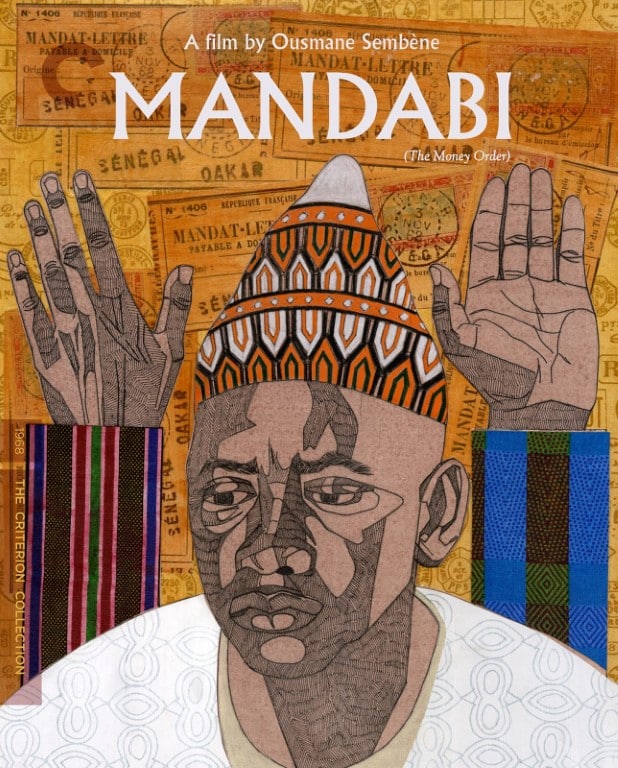

#1065: Mandabi (1968), dir. Ousmane Sembène

Criterion still has a lot of work to do in balancing its incredibly white and Asian-centric catalog with cinema from other parts of the world, so it’s refreshing that they’re getting their feet wet releasing the works of the godfather of African Cinema, Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène. His most famous work in the states is the 60-some minute masterwork Black Girl, but his second feature, Mandabi, is filled with a similar command of drama and a fiercely beating political heart.

Based on his own short story, Mandabi (Wolof for “money order”) tells the tale of Ibrahima Dieng (Makurdia Guey, whose barely-suppressed frustration rivals Michael Stuhlbarg’s in A Serious Man), an unemployed man of religion who suddenly comes into a windfall of 25,000 francs thanks to a nephew who’s sent a money order from America. Suddenly, the impoverished village around him swarms to his side, begging for loans and assistance, even as he has to jump through Kafkaesque bureaucratic hoops to even get the money order in the first place.

I’m always taken with Sembène’s incredible command of pace and place, the village of Mandabi filled out with dozens of vibrant characters, filmed in sun-soaked color (rare for Sembène, since he mostly liked to film in black and white) as they continue to pile their woes and pressures onto Ibrahima. And through this mixture of dark comedy and fierce tragedy, Sembène situates us in a post-colonial Africa that takes the wrong lessons from their oppressors (corruption and greed) and projects them on their own communities. (The film’s use of Wolof, which had heretofore not been featured in a full-length film, is a potent act of decolonization for African cinema.) It’s a situational comedy in some respects, an aching call to action in others, and a riveting tragedy when we eventually get to the collection of the money order itself.

Mandabi also gets a stellar treatment from Criterion, the 4K restoration making for eye-popping color and sharp renderings of every sweat-soaked close-up of Ibrahima’s anxiety-shrouded face. The film’s half-hour intro from film critic Aboubakar Sanogo is a vibrant, excited expression of Sembène’s contribution to African cinema and provides much-needed context; it’s a must-watch. The set also includes a 1970 short by Sembène, a program culled from a 2015 doc on the filmmaker, and a conversation with author and screenwriter Boubacar Boris Diop and activist Marie Angélique Savané. The booklet is also packed with a lovely essay from Tiana Reid, excerpts from a 1969 interview with Sembène, and a copy of the novella source material.

#1068: Smooth Talk (1985), dir. Joyce Chopra

As the Gay Men’s Choir of Los Angeles sang at last year’s Independent Spirit Awards, “Just all of Laura Dern.” But back when she was just some of Laura Dern, her early breakout came in 1985’s Smooth Talk, the Joyce Chopra-directed adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” It’s a film soaked in sleepy menace, which charts the liminal state of Dern’s teenage rebel Connie, someone who’s not quite a girl but not yet a woman, and is very interested in the latter part. For its first two acts, Smooth Talk is content to explore those uncertain impulses with quiet restraint, especially as they revolve around Connie’s fractured relationship with her mother (Mary Kay Place).

But it really kicks into high gear in its thriller-esque final act, where her allure catches the eye of Arnold Friend (a leering Treat Williams), who shows up in her driveway one day and begins to work his particular magic on her. It’s a tense negotiation as we watch Dern’s defenses worn down gradually by a predatory man who holds all the cards — a potent-as-ever analog to the consumptive power of male sexual desire. What follows is uncomfortable, deeply tense, and revelatory for both its stars and director Chopra, who tragically was unable to leverage this picture into broader Hollywood success.

Luckily, Smooth Talk‘s new transfer (a 4K restoration first shown at last year’s New York Film Festival) gives this soon-to-be cult classic the treatment it deserves. The always-welcome Alicia Malone guides us through many of the extras, including an NYFF conversation between Copra, Oates, and Dern and separate interviews with Chopra and David Wasco. Contemporaneous radio interviews from Chopra from 1985 are include, as well as three of her short films from the mid-70s (all of which explore similar facets of female agency and power at various stages of life). The booklet even includes the original short story by Oates, along with an Honor Moore-penned essay and a New York Times article by Oates on the adaptation of her work.

Read next: The Spool's Best New Releases

Streaming guides

The Best Live TV Streaming Services With Free Trial

The praises of live TV streaming services don’t need to be further sung. By now, we all know that compared to clunky, commitment-heavy cable, live TV is cheaper and much easier to manage. But just in case you’re still on the fence about jumping over to the other side, or if you’re just unhappy with ... The Best Live TV Streaming Services With Free Trial

How to Watch Power Book III: Raising Kanan Season 3

Season 3 of the hotly anticipated Power spin-off, Power Book III: Raising Kanan, is arriving on Starz soon, so you know what that means: it’s the ’90s again in The Southside, and we’re back with the Thomas family as they navigate the ins and outs of the criminal underworld they’re helping build. Mekai Curtis is ... How to Watch Power Book III: Raising Kanan Season 3

How to Watch Doctor Who: 60th Anniversary Specials

Ladies and gentlemen, we’re so back! To celebrate Doctor Who’s 60th anniversary, the BBC is producing a three-episode special starring none other than the Tenth/Fourteenth Doctor himself, David Tennant. And to the supreme delight of fans (that would be me, dear reader), the Doctor will be joined by old-time companion Donna Noble (Catherine Tate) and ... How to Watch Doctor Who: 60th Anniversary Specials

Which Netflix Country has Interstellar?

Maybe you’ve just seen Oppenheimer and have the strongest urge to marathon—or more fun yet, rank!—all of Christopher Nolan’s films. Or maybe you’re one of the few who haven’t seen Interstellar yet. If you are, then you should change that immediately; the dystopian epic is one of Nolan’s best, and with that incredible twist in ... Which Netflix Country has Interstellar?

Which Netflix Country Has Each Movie of The Hunger Games?

For whatever reason, The Hunger Games series isn’t available in the same countries around the world. You’ll find the first and second (aka the best) installments in Hong Kong, for instance, but not the third and fourth. It’s a frustrating dilemma, especially if you don’t even have a single entry in your region, which is ... Which Netflix Country Has Each Movie of The Hunger Games?

How to Watch ESPN With A Free Trial

One of the major concerns people have before cutting the cord is potentially losing access to live sports. But the great thing about live TV streaming services is that you never lose that access. Minus the contracts and complications of cable, these streaming services connect you to a host of live channels, including ESPN. So ... How to Watch ESPN With A Free Trial

How to Watch Paramount Network With a Free Trial

To date, Paramount Network has only two original shows on air right now: Yellowstone and Bar Rescue. The network seems to have its hands full with on-demand streaming service Paramount+, which is constantly stacked with a fresh supply of new shows. But Yellowstone and Bar Rescue are so sturdy and expansive that the network doesn’t ... How to Watch Paramount Network With a Free Trial

How to Watch WE TV With a Free Trial

Previously “Women’s Entertainment,” We TV has since rebranded to accurately reflect its name and be a more inclusive lifestyle channel. It’s home to addictive reality gems like Bold and Bougie, Bridezillas, Marriage Boot Camp, and The Untold Stories of Hip Hop. And when it’s not airing original titles, it has on syndicated shows like 9-1-1, ... How to Watch WE TV With a Free Trial

How to Watch Comedy Central With a Free Trial

It’s no coincidence that many of today’s biggest comedians found their footing on Comedy Central: the channel is a bastion of emerging comic talents. It served as a playground for people like Nathan Fielder (Fielder For You), Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson (Broad City), Tim Robinson (Detroiters), and Dave Chappelle (Chappelle’s Show) before they shot ... How to Watch Comedy Central With a Free Trial

How to Watch FX With a Free Trial

You’d be hard-pressed to find a bad show airing on FX. The channel has made a name for itself as a bastion of high-brow TV, along with HBO and AMC. It’s produced shows like Atlanta, Fargo, The Americans, Archer, and more recently, Shogun. But because it’s owned by Disney, it still airs several blockbusters in ... How to Watch FX With a Free Trial

How to Watch TNT Sports With A Free Trial

For many sports fans, TNT is a non-negotiable. It broadcasts NBA, MLB, NHL, college basketball, and All Elite Wrestling matches. And, as a bonus, it also has reruns of shows like Supernatural, Charmed, and NCIS, as well as films like The Avengers, Dune, and Justice League. But while TNT used to be a cable staple, ... How to Watch TNT Sports With A Free Trial