*NSYNC singer Lance Bass’ painful Chicago romcom tried to sell a sanitized, straight image of the singer—one that clashed with his true sexuality.

There are 102.8 miles of track to Chicago’s elevated transit system. For its riders, The ‘L’ opens up so many possibilities that we often forget it’s a closed circuit. The Loop, which circles downtown, is self-contained—but ride any train to the end of the line and you’ll soon find yourself going backward.

The spirit of Lance Bass has haunted these railways for 20 years. His film On the Line (2001) remains one of the most generally derided films about Chicago and its public transportation. Watching it now, that derision is still mostly justified. This is not about On the Line being “good, actually.”

Indeed, some of it is actively hard to watch. Its jokes are corny, even grotesque, and the story is so sweet it’ll cause a cavity, but those almost help in their quaint outdatedness. Now that Lance Bass is an openly proud gay man, what hurts is seeing all the ways On the Line forestalls any notion of queerness. The film has so many paths and suggestions where we might exit into a gay narrative. But alas, every time we do, it stops at “Doors. Closing.”

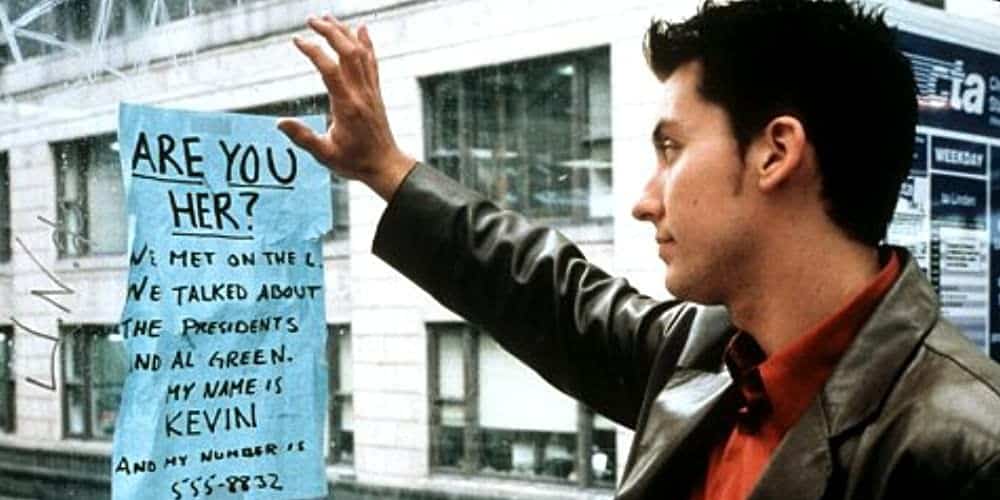

To briefly trace the film’s route: On the train home from his job at a Downtown Chicago ad agency, Kevin Gibbons (Lance Bass of NYSNC) has a meet-cute with Abbey (Emmanuelle Chriqui), the girl of his dreams. Caught up in her eyes, Kevin forgets to get her number. Kevin’s friends Rob (Bass’ bandmate Joey Fatone), Eric (GQ), and Randy (James Bulliard) devise a plan to place a personal ad and field the responses until they find the girl.

What follows is a mostly predictable comedy of errors as our train-crossed lovers criss-cross over the city with enough near misses and miscommunications to frustrate even the most frequent rider of the romcom rails. The film’s only real chemistry is found between Bass and Fatone, longtime band-and-bus-mates. Their rapport is undeniably endearing, but it only further emphasizes the gulf between Bass and Chriqui.

According to his autobiography Out of Sync, Bass had begun allowing himself to have clandestine relations with men in 2000 while in Chicago. We might assume this was during principal photography and exteriors for On the Line because it would match the shooting schedule, though Bass never directly confirms this. If Bass knew then and we know now, does the film know at all?

The film’s only real chemistry is found between Bass and Fatone, longtime band-and-bus-mates.

At best, it might have what we’d call an “inkling,” an undertone that continuously reaffirms Kevin’s heterosexuality against ever-encroaching fields of innuendo, homosociality, and homophobia. For us to understand the architecture of this cinematic closet, we should first look at its subject. We need to talk about Kevin.

Part of the reason On the Line has to work so diligently to close the door on any notion of queerness is because Kevin has such a non-normative masculinity. He falls into that Classical Hollywood trope of the virginal male, the effeminate, the nice guy, the babyface who just hasn’t found the girl.

He’s so sensitive the marketing firm he works for has put him in charge of a tween girl line for Reebok. And they’re shocked when Kevin is skeptical of globalization and mass production. He’s not like other guys in the office. And unlike his best brofriend Ross (*NSYNC bandmate Joey Fatone), who plays classic dude rock, Kevin is alternative and plays pop-punk.

With this effeminate masculinity comes the predictable millennial homophobia, which now, in 2021, becomes loaded with suspicions that time has only confirmed. There’s concern and disbelief that one of the callers “sounded like a dude.” Kevin, wouldn’t like dudes…right? When his coworker Nathan (Jerry Stiller) jokingly asks Kevin “you’re not gonna kiss me, are ya?” it now rings as both degrading and apotropaic.

And, of course, there are the continual homoerotic mispeakings of Kevin’s high school rival Brady now become ramped with possibility. Throughout the film, he’s constantly having Freudian slips that make him sound like he is romantically/sexually pursuing Kevin. “His butt is mine!…You know what I mean!” We do, Brady. But do you?

Even the things that make On the Line a critically shit movie are enhanced by a queer reading.

And speaking of butts, there’s a surprising amount of anality for a film supposedly about straight people. We learn a great deal about Nathan’s hemorrhoids. And his boss is tenderly concerned about the health and well-being of Kevin’s colon.

Even the things that make On the Line a critically shit movie are enhanced by a queer reading. With incredibly kitsch practical visuals and a narrative logic that defies linearity, it breaks with the common structure and tone of other romcoms of its time. At times, it feels like scenes are missing, perhaps censored by a hand desperately trying to keep Kevin from jumping the tracks into queerness.

…even in 2000/2001, there was still a heavy investment in keeping Lance’s persona marketable, which is to say white, boyish, and straight.

That hand could have been Harvey Weinstein’s. 2001 is during the apex of Miramax’s power and influence, yet On the Line feels decidedly anti-Miramax—which prided itself on prestige and art films. I cannot stress how much the film is neither of those. It’s an overly commercial film targeting young *NSYNC fans and few others. It’s cloyingly PG, safe and unrisky to the point of cowardice.

But now we see the perceived danger being safeguarded against. At the time it was made Lance Bass was one-fifth of *NSYNC, one of the greatest boy groups of the modern era. But as all signs pointed towards the band going their separate ways, agencies started to scramble for the next way to make money from their property while it was still commercially viable.

So even in 2000/2001, there was still a heavy investment in keeping Lance’s persona marketable, which is to say white, boyish, and straight. Given this vested interest, we can perhaps say that On the Line may not know its lead is gay, but it may have what we might call an “inkling,” just enough of an idea that the film goes out of its way to make sure the audience knows that Kevin likes girls.

But Lance is queer now and was queer then.

But some characters are allowed to be queer and it’s their presence that most dramatically points to the closet Kevin/Lance is in. As Kevin walks through to his boss’s office, he walks past several people, one of whom is a gasping gay stereotype. This nameless extra marks the world of On the Line a world where visible queerness is possible, but not for Kevin/Lance.

At the end of the film *NSYNC members, Justin Timberlake and Chris Kirkpatrick appear as Hollywood make-up and hair stylists bantering with director Eric Bross and Lance. They put on a lispy, catty, hip-swaying version of WeHo gays. Hollywood men are gay, it subliminally suggests that Lance, the first member to go to Hollywood, is queer for doing so. Both of these examples allow queerness to exist, but only as a joke and as a marker of who/what Kevin/Lance is not.

We can’t help but cringe to see him have to react to these caricatures of the identity he was forced to hide for so long and, as he reminds us in his autobiography, is actively hiding on screen.

But Lance is queer now and was queer then. We can’t help but cringe to see him have to react to these caricatures of the identity he was forced to hide for so long and, as he reminds us in his autobiography, is actively hiding on screen. He, and by extension Kevin, can’t be true.

He queerly becomes a lot like the Chicago of On the Line. With only the exteriors and establishing shots filmed in the city and the rest in Toronto, Canada, the Chicago in the film is also mostly artifice. It’s a highly calculated business decision rather than a true reflection of the city the film supposedly adores. Lance/Kevin and Chicago are both out-of-place, a there that isn’t really there.

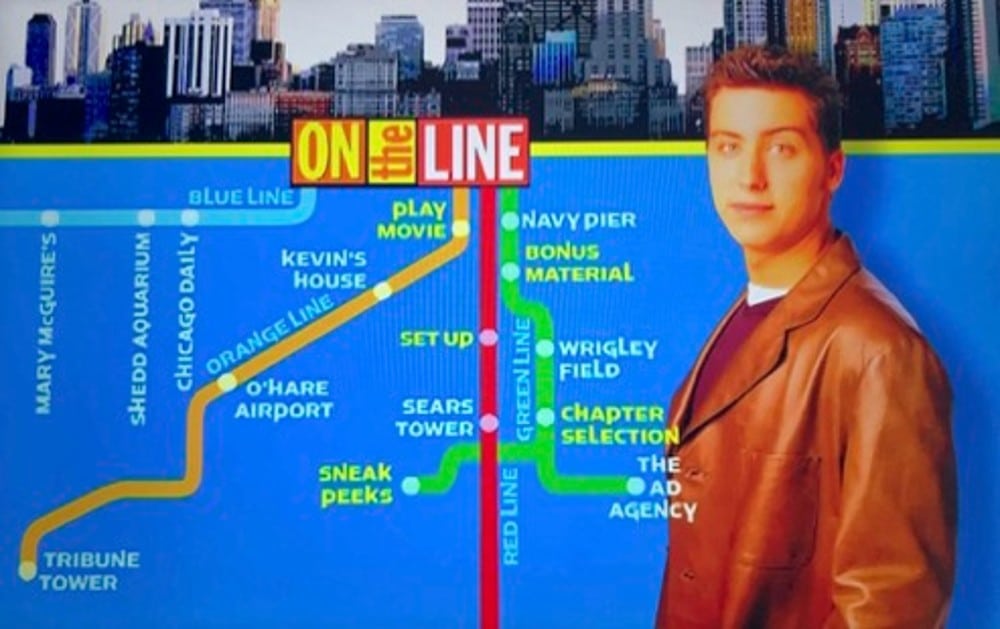

We’ll close with an image from the film’s DVD menu. If you’re not from Chicago, all you need to know is that this is absolutely not an accurate map of the city. Navigating this menu is a lot like watching On the Line today. We can follow the closed-circuit paths set for us by film producers and DVD distributors, but we know there’s a truer reality underneath.

Thankfully Lance Bass has been able to come out and live happily and openly. Fortunately, he’s now shyer about On the Line than he is about being gay. That’s what makes On the Line interesting to watch now, 20 years later. It’s not because it’s secretly great, but because we can see the alternative life underneath its train tracks.

On the Line Trailer:

Read next: The Spool's Best New Releases

Streaming guides

The Best Live TV Streaming Services With Free Trial

The praises of live TV streaming services don’t need to be further sung. By now, we all know that compared to clunky, commitment-heavy cable, live TV is cheaper and much easier to manage. But just in case you’re still on the fence about jumping over to the other side, or if you’re just unhappy with ... The Best Live TV Streaming Services With Free Trial

How to Watch Power Book III: Raising Kanan Season 3

Season 3 of the hotly anticipated Power spin-off, Power Book III: Raising Kanan, is arriving on Starz soon, so you know what that means: it’s the ’90s again in The Southside, and we’re back with the Thomas family as they navigate the ins and outs of the criminal underworld they’re helping build. Mekai Curtis is ... How to Watch Power Book III: Raising Kanan Season 3

How to Watch Doctor Who: 60th Anniversary Specials

Ladies and gentlemen, we’re so back! To celebrate Doctor Who’s 60th anniversary, the BBC is producing a three-episode special starring none other than the Tenth/Fourteenth Doctor himself, David Tennant. And to the supreme delight of fans (that would be me, dear reader), the Doctor will be joined by old-time companion Donna Noble (Catherine Tate) and ... How to Watch Doctor Who: 60th Anniversary Specials

Which Netflix Country has Interstellar?

Maybe you’ve just seen Oppenheimer and have the strongest urge to marathon—or more fun yet, rank!—all of Christopher Nolan’s films. Or maybe you’re one of the few who haven’t seen Interstellar yet. If you are, then you should change that immediately; the dystopian epic is one of Nolan’s best, and with that incredible twist in ... Which Netflix Country has Interstellar?

Which Netflix Country Has Each Movie of The Hunger Games?

For whatever reason, The Hunger Games series isn’t available in the same countries around the world. You’ll find the first and second (aka the best) installments in Hong Kong, for instance, but not the third and fourth. It’s a frustrating dilemma, especially if you don’t even have a single entry in your region, which is ... Which Netflix Country Has Each Movie of The Hunger Games?

How to Watch ESPN With A Free Trial

One of the major concerns people have before cutting the cord is potentially losing access to live sports. But the great thing about live TV streaming services is that you never lose that access. Minus the contracts and complications of cable, these streaming services connect you to a host of live channels, including ESPN. So ... How to Watch ESPN With A Free Trial

How to Watch Paramount Network With a Free Trial

To date, Paramount Network has only two original shows on air right now: Yellowstone and Bar Rescue. The network seems to have its hands full with on-demand streaming service Paramount+, which is constantly stacked with a fresh supply of new shows. But Yellowstone and Bar Rescue are so sturdy and expansive that the network doesn’t ... How to Watch Paramount Network With a Free Trial

How to Watch WE TV With a Free Trial

Previously “Women’s Entertainment,” We TV has since rebranded to accurately reflect its name and be a more inclusive lifestyle channel. It’s home to addictive reality gems like Bold and Bougie, Bridezillas, Marriage Boot Camp, and The Untold Stories of Hip Hop. And when it’s not airing original titles, it has on syndicated shows like 9-1-1, ... How to Watch WE TV With a Free Trial

How to Watch Comedy Central With a Free Trial

It’s no coincidence that many of today’s biggest comedians found their footing on Comedy Central: the channel is a bastion of emerging comic talents. It served as a playground for people like Nathan Fielder (Fielder For You), Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson (Broad City), Tim Robinson (Detroiters), and Dave Chappelle (Chappelle’s Show) before they shot ... How to Watch Comedy Central With a Free Trial

How to Watch FX With a Free Trial

You’d be hard-pressed to find a bad show airing on FX. The channel has made a name for itself as a bastion of high-brow TV, along with HBO and AMC. It’s produced shows like Atlanta, Fargo, The Americans, Archer, and more recently, Shogun. But because it’s owned by Disney, it still airs several blockbusters in ... How to Watch FX With a Free Trial

How to Watch TNT Sports With A Free Trial

For many sports fans, TNT is a non-negotiable. It broadcasts NBA, MLB, NHL, college basketball, and All Elite Wrestling matches. And, as a bonus, it also has reruns of shows like Supernatural, Charmed, and NCIS, as well as films like The Avengers, Dune, and Justice League. But while TNT used to be a cable staple, ... How to Watch TNT Sports With A Free Trial